The Setting Sun (39 page)

Authors: Bart Moore-Gilbert

That directive’s immediately countermanded by another, stamped ‘Home Department’ and dated two days later. It’s also signed by Smith: ‘I suggest that Mr Moore-Gilbert should be appointed as Additional Asst. Supdt. of Police, of the Satara District and not in the Belgaum District. This recommendation is made as the result of discussion I have had today with the District Magistrate, Satara, and the D.I.G.P. [Deputy Inspector-General of Police], C.I.D. Conditions in the Satara District have deteriorated sensibly in the last three or four weeks and I consider, therefore, that Mr Moore-Gilbert should go first to Satara and be diverted later if necessary to Belgaum.’

There are further orders, from the ‘Political and Services Department’. The first confirms Bill’s appointment as ‘officer on special duty’ in Ahmedabad after the period of long leave ‘ex-India’ he took in 1946. There’s no clue here as to where he went, but I’m beginning to suspect he used it to make his first visit to Tanganyika, to visit my grandparents and see if he could make a life there. I can’t imagine he’d have taken my mother and the young son from her first marriage somewhere so far away, just on spec.

A couple of documents signed by Bill himself relate to his time in Ahmedabad. One requests funds for a temporary shorthand typist to assist him in the preparation of a Home Guards Training Manual. A subsequent report states that he’s succeeded in engaging someone. But Bill adds a postscript: ‘In this connection, please communicate directly with the D.S. [District Superintendent] Police, Ahmedabad as I have relinquished charge as S.P. [Superintendent of Police] Special duty and am proceeding to Ratnagiri.’ There’s one final order, dated July 1947: ‘Mr SM. Moore-Gilbert, I.P., Dist. Supt. Police, Ratnagiri, is granted leave ex-India on average pay for eight months followed by leave on half average pay for one year, three months and twenty-eight days from 15 August, 1947, preparatory to retirement.’

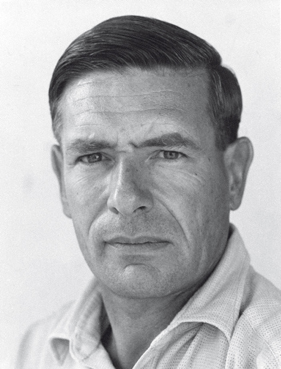

Portrait of Bill, months before he died

Did Bill only make up his mind at the last moment to leave, the very day of Indian Independence? Whatever, it seems a very generous redundancy package, ample to get married and buy a stake in my grandparents’ coffee farm.

‘Could I get a photocopy of these documents?’ The ones with Bill’s signature would be precious.

Rajeev looks uneasy. ‘They’re not supposed to have been taken from the archives. A friend did it for me.’

How on earth did he arrange that? Evidently I’m not hiding my disappointment well.

‘Alright then, but we’ll have to do it in my special place,’ Rajeev says. ‘It’s on the way.’

‘Where are we going?’

‘I want to try one last place to see if we can find those confidential weekly reports. Bring Shinde.’

‘Has Poel come up with anything?’

My host shakes his head apologetically as he gets up. ‘I’ll explain later.’

I gather my things.

‘Before we go, have a look at these.’

He leads me to the desk. The comics are indeed vintage, mainly American ones with heroes like John Steel, Robot Archie and Rick Random, the lurid colours now respectably dulled by age.

‘I used to buy them as a kid. They were smuggled into India. Morally corrupting and all that. Glad I looked after them. Worth a lot of money now. I might need to cash them in for my retirement.’

Elvis, comics. What other surprises does Rajeev have up his sleeve in our last hours together?

‘When do you retire?’

Rajeev laughs ruefully. ‘Four months, three weeks and a day.’

We head East from Rajeev’s flat. I’m going to badly miss this bustle and spectacle, the warm milling crowds. India, or Maharashtra at least, has got right under my skin. I can’t believe it took me so long to get here. What must Bill have felt on his last day in Bombay Province, after nearly nine years of service? Perhaps, like me, he was bereft, even if the adventure of Africa was beckoning. How did he spend his final hours? With friends? Arm-in-arm with one of the ‘girl-friends’ in Aunt Pat’s photo album? Packing and last-minute shopping for the curios which found their way into my childhood home in Tanganyika? Perhaps he strolled in civvies, before enjoying a final curry with Bombay Duck, trying – like me – to make

sense of his time here. The closeness I felt to Bill during my first tentative explorations of Mumbai surges up again and I miss him piercingly.

In the cramped photocopy shop tucked away up an alley, the proprietor behaves as if he’s receiving a distinguished visitor. Rajeev disappears after him into a back room, returning a few minutes later with two manila envelopes.

‘Make sure you don’t leave it anywhere,’ he mutters, handing me mine.

I put it carefully away in my knapsack and we set off again, in the direction of the old Victoria railway terminus and Crawford Market. After fifteen minutes, however, we veer south-east. There are signs for Cama Hospital and we turn up a nondescript lane which skirts its perimeter.

‘Want to show you something,’ Rajeev says.

We stop at a junction, where the roads are barely wide enough for two vehicles to pass. It’s a shabby and unremarkable site, a temporary-looking tea stall set up next to a back entrance to the hospital.

‘This is where they killed poor Kamte, whose grandfather was Moore-Gilbert’s colleague. Those bloody bearded bandits. They just want to go backwards. Serves them right what’s going on in Gaza.’

He’s visibly upset, so I don’t ask if he’s seen the latest television pictures.

‘They hid behind that gate after they attacked the hospital. When the police vehicle stopped at this junction, they shot Kamte and his colleagues in cold blood. One constable survived by playing dead. They dragged the bodies out and drove off on their rampage downtown.’

I remember the images of the boxy black-and-white vehicle, like the one I was lent in Satara, careering southwards, pedestrians throwing themselves to the ground as the only Mumbai attacker to survive sprayed sub-machine-gun fire out of the passenger window.

‘I’m very sorry, Rajeev,’ I mutter, patting him on the shoulder.

‘Why was Kamte allowed to bleed to death just a hundred yards from the hospital?’ Face working, he leads me on.

Soon we’re passing through a rather more imposing gate, into an annexe of what Rajeev explains is the headquarters of the City police, the senior branch of the Maharashtra force, and of the Bombay service before it. We’re nodded through with barely a glance. Either he’s known, or security’s ridiculously lax, especially given the recent attacks. We enter a modern three-storey building, where Rajeev chats to the duty sergeant.

‘Special Branch number two,’ Rajeev informs me. ‘The City lot have their own archives, separate from the State police where you went before. It’s a long shot.’

We’re shown into a clammy ground-floor room where the windows are wide open onto a courtyard. A slight man with a scholarly air and bullfrog cheeks stands up to greet Rajeev effusively.

‘My friend from London University I was telling you about.’

After the compulsory tea, Rajeev shows him Shinde’s book. The archivist skims the footnotes and bibliography.

‘I’ll have to consult. Of course, there’s the issue of permission.’

‘I’ve phoned Ramanandan,’ Rajeev reassures him. ‘So has Mr Poel.’

‘Who’s Ramanandan?’ I ask.

‘Assistant commissioner, City. Poel’s counterpart. A lot of intelligence was collated here in those days, since City was senior.’

While the archivist leaves the room to confer with colleagues, we chat about the frustrations I’ve encountered hunting down the confidential reports.

‘Yes. And no wonder all the “Terrorism” files were missing when you went to look,’ Rajeev nods lugubriously. ‘Poel and

I, we made some inquiries. Seems the whole lot were taken by someone inside the force.’

‘What?’

‘Apparently he wanted to write a history of the Patri Sarkar. He disagreed with some interpretations of the police role in events.’

‘Did he do so?’

Rajeev shakes his head. ‘He died before finishing.’

‘So where are the files?’

My friend grimaces. ‘I suspect they’re with his widow. She lives in Pune, apparently. Someone’s going to contact her.’

Too late for me, I think ruefully. It’s criminal that such a precious historical resource might be mouldering in some monsoon-damp basement.

‘And many of the other files you looked at have been tampered with as well. After Independence, some of that stuff would have been dynamite. It could have ruined a few careers, especially the material on police informants and collaborators.’

‘Please to follow,’ the librarian invites us when he returns. ‘We need to go into the main holdings.’

It’s an extraordinary room, the size of a tennis court, no windows, like a bank strongroom. Floor-to-ceiling shelves are stocked with metal canisters, like ammunition boxes, all with handwritten labels. These records would seem to have a better chance of being preserved than most I’ve seen.

‘Right back to the earliest days,’ the librarian affirms.

The entire archive of the Bombay City police. What stories must be hidden here. Yet very few scholars come these days, our guide tells us. There’s little interest in the history of the security services during the Raj. We find ourselves at a desk where a young man in Gandhi glasses is studying Shinde’s book, glancing intermittently across at a computer screen. He looks doubtful.

‘I’ve checked the references on the pages you marked. I’m afraid they’re not in this building. Even though some

of them have Special Branch file numbers. If you’ve already looked in State Police HQ, there’s only one other place they might be.’

Rajeev and I glance at each other. ‘Home Department at Mantrale,’ we intone simultaneously.

‘Sorry,’ my friend murmurs.

But I smile. The possibility of hearing Bill’s voice and understanding his perspective on events has kept me going through some tough times on this journey. Since Ratnagiri, however, I’ve been increasingly comfortable that mysteries remain. They might be reason to come back to India sometime, get to the Home Department archives in Nasik and Ahmedabad, see some of the friends I’ve made again. I’m already beginning to miss them.

Back in the office, I chat with the chief archivist about his treasures, while Rajeev goes to relieve himself. My curiosity eventually gets the better of me.

‘How come Mr Divekar has access here? No one’s asked any questions,’ I venture.

The librarian seems surprised that I don’t know. ‘Well, he worked at State Police Headquarters for eighteen years.’

What? No wonder Rajeev was able to turn up the documents we’ve just photocopied.

‘Anyway, these raw people can get in anywhere.’

Raw? Something rings a bell. An acronym in the newspapers? But before I can ask, my friend returns, with another docket which he’s studying intently.

‘Here,’ Rajeev says when he’s finished, ‘you might be interested in this.’

I can’t believe my eyes: the confidential internal police report on the Mumbai attacks. I’m amazed to see that the death toll’s put at 123, when in the newspapers the lowest figure is in the 170s, sometimes much higher. Who’s been inflating the figures and why? Who’ll write the true history of the Mumbai attacks, I wonder, recalling the problems with

Shinde’s ‘official’ account of the Parallel Government. Will this document, too, disappear from the records or be tampered with?