The Silk Road: A New History (4 page)

Read The Silk Road: A New History Online

Authors: Valerie Hansen

The first written description of the Silk Road trade concerns Zhang Qian (d. 113

BCE

), a Chinese envoy from Chang’an to Central Asia in the second century

BCE

, during the reign of Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty (reigned 140–87

BCE

). The emperor hoped that Zhang Qian would persuade the Yuezhi people, living in the Ferghana region of modern-day Uzbekistan, to ally with the Chinese against their common enemy to the north, the Xiongnu tribal confederation, based in modern-day Mongolia. The earliest surviving account about Zhang Qian was written at least 150 years after his trip and does not provide many basic facts about his journey, such as his exact itinerary.

It is clear, though, that Zhang went through Xiongnu territory on his way to the Yuezhi. The Xiongnu imprisoned Zhang, and it took him about ten years to escape. Nonetheless, he still proceeded to visit the Yuezhi. On his return, sometime around 126

BCE

, he gave the emperor the first detailed information the Chinese received about the different peoples of Central Asia.

20

Zhang Qian was extremely surprised to discover that Chinese merchants and trade goods had preceded him to Central Asia. In the markets of Bactria, in modern-day northern Afghanistan, Zhang Qian saw bamboo and cloth manufactured in the Chinese province of Sichuan, several thousand miles away. The Chinese goods must have traveled overland.

After Zhang Qian’s return, the Han dynasty gradually extended its control into the northwest. By the end of the second century

BCE

it secured the Gansu corridor and Dunhuang. Each time the Chinese army conquered a new region, it constructed beacon towers at fixed intervals. If a disturbance occurred, the soldiers guarding the beacon tower lit torches to alert the men in the next tower, and so on down the line until the news reached the first garrison that could dispatch troops to the troubled area. In addition to the beacon towers, the Han military also established garrisons in the newly conquered territories. Documents in the form of bamboo slips recording army purchases of clothing and grain from the local people have been found at Juyan (Ejina Banner, Inner Mongolia, 90 km northeast ofJinta County, Gansu) and Shule (near Dunhuang and Jiuquan, Gansu).

21

The largest cache of early documents from the Silk Road was excavated from just such a Chinese garrison at Xuanquan, located 40 miles (64 kilometers) east of Dunhuang.

22

A square dirt wall, 55 yards (50 meters) on each side, surrounded the complex, which had a stable for horses on its southern edge. Officials traveling on government business were entitled to get fresh mounts at the garrison, which also functioned as a postal station. On the northern and western edges of the enclosure were waste disposal areas; the western garbage pit extended 1.3 yards (1.2 m) underground at its greatest depth. The 2,650 artifacts from the site included coins, farm tools, weapons, iron cart parts, and utensils such as combs and chopsticks, as well as foodstuffs like grain, garlic, walnuts, almonds, and animal bones.

23

There are more than 35,000 discarded documents from the Xuanquan site: 23,000 wooden slips with Chinese characters on them, and 12,000 bamboo slips trimmed to size, apparently intended for later use. About two thousand of the slips bear dates between 111

BCE

and 107

CE

, the years when the garrison was in use.

The slips are written on wood and bamboo because paper was just spreading to Central Asia at this time. Invented in China during the second century

BCE

, paper was first used as a wrapping material and not for writing. The official histories record, for example, that in 12

BCE

a murderer used poison wrapped in paper.

24

Some of the earliest paper scraps found at Xuanquan, dating to the first century

BCE

, also bear the names of medicines, confirming the early use of paper as a wrapping material.

Not until four centuries later, in the second century

CE

, did paper come into widespread use as writing material in China. It took even longer for paper to replace wood and bamboo as the most common writing material along the Silk Road. Because paper was always expensive, people wrote on other materials like leather and tree bark. The documents at Xuanquan consist mostly of wooden slips tied together to form bunches (much like a placemat made from Popsicle sticks).

The documents from the Xuanquan site include much everyday correspondence among the officials stationed at the Xuanquan postal station and other nearby locations, notices of new edicts issued by the emperor, announcements of runaway prisoners, and private letters. The scribes at Xuanquan distinguished among different types of wood: they reserved higher-quality pine for imperial edicts and used poplar and tamarisk, which warped easily, for routine documents and correspondence.

Since Xuanquan was the final stop before Dunhuang on the way out of China, almost all envoys passed through it once on their journey into Han-dynasty China and again when leaving. Chinese geographic sources from the Han dynasty list more than fifty kingdoms in Central Asia. Although the Chinese documents usually refer to these rulers as kings, each domain often consisted of a single oasis with a population as small as several hundred people and no larger than several thousand. These oases resembled small city-states more than kingdoms.

25

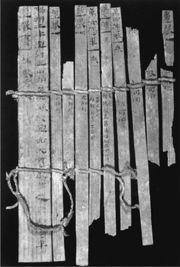

DOCUMENTS BEFORE PAPER

Even after paper spread from China to the Silk Road in the second century

BCE

, some documents continued to be written on wooden slips. The earliest paper was used to wrap medicine, and it was not until the third century

CE

that the transition to using paper for writing was complete. These slips record the carts requisitioned by a garrison. Bound together by string, they were rolled up when stored. Characters were read in columns from top to bottom and from right to left, so one began reading at the upper right-hand corner, and read vertically down the first slip, returning to the top of the second slip, and continuing in the same way until finishing at the bottom left corner.

Big or small, these different states dispatched envoys to visit the Chinese capital to present gifts to the emperor, whom they acknowledged as their superior, and to receive gifts in return. Among the most treasured gifts were the horses that grazed in the Central Asian grasslands; because they roamed free, they were always stronger than the smaller, less powerful Chinese breeds that ate fodder hand-carried to their stables. The Chinese prized the heavenly horses of the Ferghana valley, in Uzbekistan, most of all. Even in this early period, during the Han dynasty, it is impossible to distinguish between official trade, in which an envoy brought a gift (often animals such as horses or camels) and received something for his ruler in return, and private trade, in which the same envoy might present an identical animal to the Chinese and keep the return gift for himself.

The gift-bearing delegations from Central Asian kingdoms varied in size. On some occasions delegations were a thousand strong: the king of Khotan, for example, headed a single group of 1714 people.

26

More typical was a delegation from Sogdiana, in 52

BCE

, that included two envoys, ten aristocrats, and an unspecified number of other followers, who led nine horses, thirty-one donkeys, twenty-five camels, and a cow.

27

These delegations traveled on fixed itineraries and carried travel passes listing the towns, in order, they were allowed to visit. According to the law of the Han dynasty, which drew on even earlier precedents, anyone going through a checkpoint, on land or by water, needed a travel pass, called a

guosuo

(literally “passing through a place”).

28

Several of the Xuanquan documents list all the stops between Dunhuang, the first town within the empire, and the Han-dynasty capital, either Chang’an in the first century

BCE

or Luoyang in the first century

CE

. Delegations were not permitted to stray from these routes. At each stop, officials counted the people in each delegation and the animals traveling with them to ensure that the party exactly matched the one enumerated on the travel pass. Officials could emend these passes and could also issue new passes. They checked the delegations when they went through Xuanquan on their way to China and again when they left Xuanquan, usually about six months later, on their way back to Central Asia. The cooks at Xuanquan kept detailed records of their expenditures on food for each guest, whether Chinese or foreign, whom they identified by rank and direction of travel (east or west).

29

The wooden slips from Xuanquan are remarkably detailed. One of the longest records describes a dispute occurring in 39

BCE

, when four Sogdian envoys petitioned Chinese officials to protest the low prices they had received for camels. The Sogdians maintained that Chinese officials had paid them the rate for thin, yellow camels, but they had actually delivered more valuable fat, white camels. The Sogdian envoys not only had a clear sense of market values but also sufficient confidence in the predictability of the system to protest when the prices diverged from their expectations. The Sogdians also expected, as envoys carrying the appropriate credentials, to be housed and fed at each stop along the way, but ended up paying for their meals instead. The officials at Dunhuang who heard the dispute in 39

BCE

concluded that the Sogdians had been appropriately compensated. One possible explanation for the harsh treatment of the envoys: the Han-dynasty officials bitterly resented the Sogdians for cooperating with their longtime enemy, the Xiongnu, so they retaliated by underpaying them.

30

The Xuanquan documents define an entire world, a world that included oases on the far western edge of China, near the modern city of Kashgar, as well as those beyond modern China’s border in Uzbekistan, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. The rulers of these different Central Asian oases participated in the systematized exchange of diplomatic envoys with the Chinese emperor of the Han dynasty, and envoys from these different points regularly traveled the Silk Road on their way to the Chinese capital.

Of the many foreign embassies that visited the Han-dynasty emperors to present tribute, only one was conceivably from Rome. An envoy from the ruler of Da Qin (literally the “Great Qin”), the official history reports, arrived by sea in 166

CE

. Da Qin sat on the western edge of the world known to the Chinese and displayed many characteristics of a utopia; only in some instances does the term refer specifically to Rome. The Da Qin emissary presented ivory and rhinoceros horn, typical products of Southeast Asia. Many suspect that this envoy was an imposter who claimed to be from a distant, barely known place in order to receive permission to trade. This single mention is intriguing but hardly conclusive.

31

As the Xuanquan documents and other materials reveal, the Han dynasty initiated regular trade along the routes around the Taklamakan for purely strategic reasons—they sought alternative routes to Central Asia so that they could bypass the Xiongnu, their constant enemy. Official envoys might occasionally engage in private trade, but always as a sideline to their official business. Their movements were never spontaneous but took place along carefully planned and recorded itineraries. For all their detail about Chinese trade with the Central Asian oases, the Xuanquan documents make no mention of any place west of the Kushan Empire (in northern Afghanistan and Pakistan) and certainly not of Rome itself.

Unfortunately, no documents with a level of detail comparable to the Xuanquan documents have been excavated on the European side, so analysis of Europe’s trade must rely on known Greek and Latin texts. One of the most informative sources is the

Periplus of the Erythraean Sea,

a book written sometime in the first century

CE

by an anonymous merchant living in Egypt who wrote in Greek.

32

After describing the various ports of east Africa, Arabia, and India, the

Periplus

concludes with an account of the lands lying beyond the known world:

Beyond this region [an island in the sea to the east of the port at the mouth of the Ganges], by now at the northernmost point, where the sea ends somewhere on the outer fringe, there is a very great inland city called Thina from which silk floss, yarn, and cloth are shipped by land … and via the Ganges River.… It is not easy to get to this Thina; for rarely do people come from it, and only a few.

33