The Silk Road: A New History (8 page)

Read The Silk Road: A New History Online

Authors: Valerie Hansen

Inside the hall, Stein’s men dug through a refuse heap and found eleven wood slips with Chinese characters on both sides; eight were legible. Each records the name of the giver and the recipient—the king, his mother, his wife, the heir apparent in the royal family, and a courtier.

34

The front side of one, for example, says “Minister Chengde bows his head to the ground and sincerely presents this piece of jade. He bows again to ask,” while the reverse gives the name of the recipient, in this case, “the great king.”

35

These tags suggest that a Chinese advisor, who visited, or lived at, the Jingjue court sometime early in the first century

CE

, taught the ruler to attach them to gifts. Three of the wood slips from room 14 use the distinct language of the usurper Wang Mang (reigned 9–23

CE

), who founded the Xin (“New”) dynasty, a fourteen-year-long interregnum between the Former and Later Han dynasties.

36

Several other Chinese documents from the refuse pit in Niya house 14 mention envoys: “The seat of the envoy of the King of Ferghana [Dayuan]; below him on the left, the Great Yuezhi.”

37

These various documents all indicate that the Chinese must have had some type of outpost at Niya before and after the start of the Common Era.

According to Chinese laws, every time a traveler arrived in a new place within China, he had to present his

guosuo

travel document to local officials who verified that he was the person whose name appeared on the pass. Travel passes found at Niya, which date to the third century, state whether or not the traveler was a free man, give a physical description, and specify his destination. One, for example, describes a thirty-year-old traveler “of medium build, black hair, big eyes, with moustache and beard.” They also list the itinerary of the travelers, who had to keep to a predetermined route. Two of the wood slips instruct officials what to do if someone’s pass was missing, but do not reveal what actually happened when local officials discovered the problem. Did the border officials simply issue a new pass? Or did they punish the errant merchants? Regardless, Chinese officials at Niya were clearly aware of existing regulations about travel passes.

38

Assessing Chinese power in the region during this early period has direct political implications for today. The Chinese government’s legitimacy in Xinjiang rests partially on the precedent of Han-dynasty control. But that claim seems weaker if local rulers were largely independent and simply hosted Chinese garrisons and received the occasional advisor or envoy, as surviving documents indicate.

HOUSE 26 AT NIYA

After he finished excavating house 26 at Niya in 1906, Stein asked his workers to place the double wooden bracket that provided support for the main room’s ceiling on a pillar so that it could be photographed. Typically Gandharan, the carved wooden bracket shows a vase with fruit and flowers at the center and a mythical animal with wings, a dragon’s head, and a horse’s body. Measuring 9 feet long and 1.5 wide (2.74 m by .46 m), the bracket was too large to transport. Stein’s men sawed it into pieces and hollowed it out so that it could be shipped to London. Courtesy of the Board of the British Library.

Whatever they suggest about the Chinese presence at the turn of the Common Era, the wooden slips from house 14 at Niya reveal little about the lives of those who lived at the site. Fortunately, material evidence supplements these early Chinese documents. Niya’s ancient residents joined several wooden beams together to form a foundation and slotted vertical poles into the floor beams to make walls. They then packed the walls with grasses and mats to protect occupants from the wind. They crafted roofs from beams, too. The houses ranged from small dwellings with just one room to larger houses with multiple rooms with walls over 16 feet (5 m) long. Stein and Hedin found a few elaborate carvings at Niya and Loulan; their designs matched wooden objects made in the Gandhara region, confirming that their makers had come to Xinjiang from Pakistan and Afghanistan.

The extreme dryness of the Niya and Loulan sites has preserved about one hundred ancient corpses of the residents. At Loulan Stein found one corpse with “fair hair,” while another had a “red moustache.” Both he and Hedin sensed that these desiccated corpses did not look either Chinese or Indian. All subsequent excavators in the region have marveled at the excellent state of preservation of corpses whose light skin, fair hair, and heights nearing six feet (1.8 m) mark them as Caucasoid. It seems most likely that the original inhabitants of the Kroraina Kingdom, like many others living in Central Asia, originally came from somewhere on the Iranian plateau.

39

Burials at the Niya and Loulan sites have much to tell us about the lives of those interred there because they carried their most precious articles with them to the afterlife. In 1959 a team of ten archeologists from the Xinjiang Museum entered the desert on camels (lacking desert vehicles) and walked seven days before reaching the site where they discovered the graves. They found a huge coffin measuring 6.5 feet (2 m) long with four wooden legs, which they dated between the second and fourth centuries

CE.

40

The coffin held the corpses of a man and woman and two wooden staffs for carrying their possessions. The man carried a bow and four arrows in an arrow holder, while the woman had a makeup box along with combs and other female grooming articles. Although the clothing of the deceased couple had decayed wherever it touched their skin, the archeologists managed to recover pieces from more than ten different textiles, some cotton, some silk. The presence of the two fabrics testified to Niya’s location midway on the overland routes linking China with the West.

While the knowledge of how to raise silkworms and to spin silk originated in central China and traveled west, cotton traveled east to Niya from West Asia. This and another tie-dyed piece of cotton are the earliest cotton textiles unearthed in China to date.

41

A Chinese encyclopedia reports that in 331

CE

the king of Ferghana (in western Uzbekistan) gave cotton cloth and glass to a north Chinese ruler, confirming the introduction of cotton from the west.

42

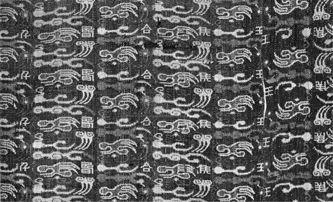

COTTON TEXTILE FROM NIYA

A distinctive printed cotton textile from the tomb had different squares showing a checkerboard pattern, a Chinese dragon, a goddess holding a cornucopia, and the tail and two paws of an animal whose body has been cut off. The dragon motif is clearly of Chinese origin, but the goddess is Tyche, the Greek city guardian who frequently appears in the art of Afghanistan. Because Tyche is often paired with Hercules, it is likely that the paws and the tail are those of Hercules’s lion.

The Niya site also produced cocoons and seeds from mulberry trees, the main foodstuff of silkworms. The residents knew how to spin silk thread and how to make a simple tabby weave (one thread over, one under—a basket weave), but they did not have the sophisticated looms required to make the elaborate silk brocades found in the coffin. Those found in 1959 included gloves and socks for the man and a pillow for the couple, all cut from the same bolt of cloth with seven Chinese characters woven into the design: “increased longevity over the extended years and multiple sons and grandsons.” These twin goals—a long life and many male descendants—date back to the earliest times in China. These textiles, which closely resemble one of the brocades found at Palmyra, were clearly of Chinese manufacture, as was a mirror found with them. Four characters along the rim of bronze mirror urged the deceased tomb owner: “You should be a high official.”

43

While it is unclear if the deceased couple could read Chinese, the placement of the inscribed textiles and mirror in the coffin indicate that these were valued items.

A 1995 expedition to Niya unearthed eight more burials, three in rectangular coffins, five in boat-shaped coffins made from poplar trees that had been hollowed out after being set on fire. The coffin in the largest tomb (M3) contained the desiccated bodies of a man and a woman that were remarkably well preserved (shown in color plate 7). As in the tomb found in 1959, gender roles were apparent. The man was buried with bows, arrows, a small dagger, and a knife sheath; his wife had a makeup box, a bronze mirror of Chinese manufacture, combs, a needle, and small bolts of cloth. Knife marks stretching from the man’s ear to his neck are from the wound that caused his death, while his wife’s body was unscarred, suggesting death by suffocation so that she could be interred at the same time.

CHINESE SILK FROM NIYA

Artfully woven into the fabric were Chinese characters saying “kings and lords shall be married for thousands of autumns and tens of thousands of years; it is right that they bear sons and grandsons.” This is one of thirty-seven textiles found in a single burial at Niya, making it one of the most important finds along the Silk Road. Courtesy of Wang Binghua.

The couple lay underneath a single-layered coverlet of blue silk brocade with a pattern of stylized dancers in red, white, and brown. The deceased wore complete sets of clothing.

A slightly later tomb, numbered M8, also contained a deceased couple, as well as some textiles with Chinese characters on them and a simple clay vessel with the Chinese character for king on it.

44

The use of the words “king” and “lord” in the textiles from tombs M3 and M8 suggests that these are gifts from the Chinese central authorities to a local king. At some point after 48

CE

the Shanshan Kingdom “incorporated” the Jingjue Kingdom, we learn from the

History of the Later Han.

45

And so the Niya site, which had served as the capital of the Jingjue state, became part of the larger Shanshan Kingdom.

A contemporaneous burial from the site of Yingpan (southwest of Loulan) contrasts sharply with the Niya burials, because the corpse was buried in wool, not cotton or silk.

46

The deceased man wears a red woolen robe with an elaborate design composed of pairs of facing pomegranate trees, animals, and human figures. Naked cherubic figures brandish swords and lassos as they confront one another in a combat stance. With two interwoven layers, this textile is too complex to have been made by local weavers. It was probably made in Bactria, far to the west, where local artisans modified the Greco-Roman motifs first introduced to the region by the armies of Alexander of Macedon in the fourth century

BCE.

47

Archeologists have speculated about the identity of this beautifully dressed corpse. The former director of the Xinjiang Archaeological Institute, Wang Binghua, suggests the he may have been a ruler of yet another small oasis kingdom mentioned in the official histories, the Kingdom of Shan (literally “The Hill Kingdom”), whose southeastern border abutted the Shanshan Kingdom.

48