Read The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment And The Tuning Of The World Online

Authors: R. Murray Schafer

The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment And The Tuning Of The World (7 page)

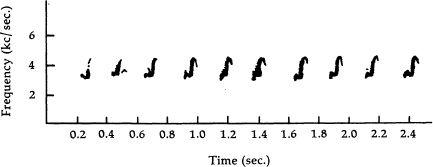

A sound spectrograph distinguishes clearly among bird notes having different tonal qualities: (a) nightingale note, very pure, with harmonics; (b) white-throated sparrow, clear whistle; (c) marsh warbler, musical trill; (d) clay-colored sparrow, toneless buzz; (e) budgerigar, noisy flight squawk

.

But despite these similarities, it is obvious that to whatever extent the birds are deliberately communicating, it is for their own benefit rather than ours that their vocalizations are designed. Some men may puzzle over their codes, but most will be content merely to listen to the extravagant and astonishing symphony of their voices. Birds, like poems, should not mean, but be.

Bird SymphonieS Of the World

Each territory of the earth will have its own bird symphony, providing a vernacular keynote as characteristic as the language of the men who live there. In Paris, Victor Hugo listened to the birds in the Luxembourg Gardens during May, the month of mating.

The quincunxes and flower-beds sent balm and dazzlement into the light, and the branches, wild in the brilliancy of midday, seemed trying to embrace each other. There was in the sycamores a twittering of linnets, the sparrows were triumphal, and the woodpeckers crept along the chestnuts, gently tapping the holes in the bark …This magnificence was free from stain, and the grand silence of happy nature filled the garden,—a heavenly silence, compatible with a thousand strains of music, the fondling tones from the nests, the buzzing of the swarms, and the palpitations of the wind.

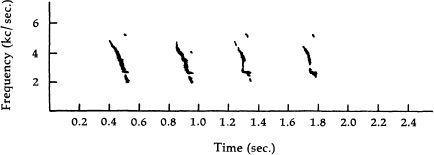

A sound spectrograph of the pleasure notes (above) and distress call (below) of a three-day-old chick

.

Such rich polyphony is absent from the North American grasslands. On a plain near Pittsburgh a century ago, a German writer fourd “absolutely nothing. … Far and wide there was not a bird, nor a butterfly, nor the cry of an animal, not the hum of an insect.” In the grasslands, sounds evaporated as if they had never been uttered. In the Russian Steppes, bird-song was also often isolated: “Everything might be dead; only above in the heavenly depths a lark is trilling and from the airy heights the silvery notes drop down upon adoring earth, and from time to time the cry of a gull or the ringing note of a quail sounds in the steppe.” Occasionally only a single species is heard: “How enchanting this place was! Orioles kept making their clear three-note calls, stopping each time just long enough to let the countryside suck in the moist fluting sounds down to the last vibration.” And in winter the birds blended with sleigh bells: “What could be more pleasant than to sit alone at the edge of a snowy field and listen to the chirping of the birds in the crystal silence of a winter’s day, while somewhere far away in the distance sounded the bells of a passing troika—that melancholy lark of the Russian winter.”

But in the jungles of Burma, such clarity was impossible to find, as Somerset Maugham discovered when he journeyed there. “The noise of the crickets and the frogs and the cries of the birds” produced a tremendous din, “so that till you become accustomed to it you may find it hard to sleep.” “There is no silence in the East,” Maugham concluded.

Ornithologists have not yet measured the statistical density of birds’ singing in different parts of the world in sufficient detail for us to make objective comparisons—comparisons that would be helpful in mapping the complex rhythms of the natural soundscape. But ornithologists have done a lot of work on another subject of interest to soundscape researchers by classifying the types and functions of bird-song. Basically these are distinguished as follows:

pleasure calls

distress calls

territorial-defense calls

alarm calls

flight calls

flock calls

nest calls

feeding calls

Equivalents for many of these can be found in human soundmaking. To take some obvious examples: the territorial calls of birds are reproduced in automobile horn blowing, their alarm calls are reproduced in police sirens and their pleasure calls in the beach-side radio. In the territorial calls of birds we encounter the genesis of the idea of acoustic space, with which we will be much concerned later. The definition of space by acoustic means is much more ancient than the establishment of property lines and fences; and as private property becomes increasingly threatened in the modern world, it may be that principles regulating the complex network of overlapping and interpenetrating acoustic spaces as observed by birds and animals will again have greater significance for the human community also.

Birds may be distinguished by the sounds of their flight. The great slow clapping of the eagle’s wing is different indeed from the tremulous shaking of the sparrow against the air. “In reality I did not see the birds, but I heard the fast whir of their wings,” wrote Frederick Philip Grove after crossing the Canadian prairies at night. The startled exodus of a flock of geese on a northern Canadian lake—a brilliant slapping of wings on water—is a sound as firmly imprinted in the mind of those who have heard it as any moment in Beethoven.

Some birds have furtive wings: “The owl’s flight is too silent, its wing is down-padded. You may hear its beautiful call, but you will not hear its flight, even though it circle right around your head in the dusk.” Only those who live close to the land can distinguish birds by the sounds of their wings in flight. Urban man has retained this facility only for insects and aircraft.

One notes with sadness how modern man is losing even the names of the birds. “I heard a bird” is a frequent reply I receive following a listening walk in a city.

"What bird?”

"I don’t know.” Linguistic accuracy is not merely a matter of lexicography. We perceive only what we can name. In a man-dominated world, when the name of a thing dies, it is dismissed from society, and its very existence may be imperiled.

Insects

The most easily recognized insect sounds for modern man are the most irritating. The mosquito, the fly and the wasp are easily distinguishable. The attentive listener can even tell the difference between male and female mosquitoes, the male usually sounding at a higher pitch. But only a specialist, such as a beekeeper, knows how to distinguish all the variants of the bee sound. Leo Tolstoy kept bees on his estate, and their sound is described in both

Anna Karenina

and

War and Peace

. “His ears were filled with the incessant hum in various notes, now the busy hum of the working bee flying quickly off, then the blaring of the lazy drone, and the excited buzz of the bees on guard protecting their property from the enemy and preparing to sting.” When a queenless hive is dying, the beekeeper knows this too from the sound.

The flight of the bees is not as in living hives, the smell and the sound that meet the beekeeper are changed. When the beekeeper strikes the wall of the sick hive, instead of the instant, unanimous response, the buzzing of tens of thousands of bees menacingly arching their backs, and by the rapid stroke of their wings making that whirring, living sound, he is greeted by a disconnected, droning hum from different parts of the deserted hive. … Around the entrance there is now no throng of guards, arching their backs and trumpeting the menace, ready to die in its defence. There is heard no more the low, even hum, the buzz of toil, like the singing of boiling water, but the broken, discordant uproar of disorder comes forth.

In his

Georgics

Virgil describes how the Roman beekeeper would “make a tinkling noise” with cymbals to attract the bees to a hive. He also describes vividly how two nests of bees would occasionally make war on one another with “a cry that is like the abrupt blasts of a trumpet.”

The sounds of insects are produced in a surprising number of ways. Some, such as those of the mosquito and the drone bee, result from wing vibrations alone. The general range of wing frequencies in insects is between 4 and upward of 1,100 beats per second, and much of the pitched sound we hear from insects is produced by these oscillations. But when the butterfly moves its wings at between 5 and 10 times per second, the result is too faint and too low to be registered. In the honeybee, the wing beat frequency is 200 to 250 cycles per second and the mosquito

(Andes cantans)

has been measured at up to 587 cycles per second (c.p.s.). These frequencies would thus be the fundamentals of the resulting sounds, but as a rich spectrum of. harmonics is also often present, the result may be a blurred noise with little discernible sensation of pitch.

Another type of sound produced by some insects is that created by tapping the ground. Such is the case in several species of termites. Large numbers of termites may hammer the ground in unison, presumably as a warning device, at a rate of about ten times a second, producing a faint drumming noise. Julian Huxley writes: “I remember waking up at night in camp, near Lake Edward, in the Belgian Congo, and hearing a strange clicking or ticking sound. A flashlight revealed that this was emanating from a column of termites which was crossing the floor of the tent under cover of darkness.”

Still other insects, such as crickets and certain ants, produce stridulating effects by drawing parts of the anatomy called scrapers across other parts called files. The result of this filing activity is a complex sound, rich in harmonics. The variety of these stridulatory mechanisms is enormous, and by far the greatest number and variety of sounds produced by insects are produced in this manner.

Among the loudest of insects are the cicadas. They produce sound by means of ridged membranes or tymbals of parchment-like texture, close to the junction of the thorax and abdomen, which are set in motion by a powerful muscle attached to the inner surface; this mechanism produces a series of clicks in the same manner as does a tin lid when pressed in by the finger. The movement of the tymbals (amounting to a frequency of about 4,500 c.p.s.) is greatly amplified by the air chamber that makes up the bulk of the abdomen, so that the sound has been heard as far as half a mile away. In countries such as Australia and New Zealand, they create an almost oppressive noise when in season (December to March), though during the night they give way to the more gentle warbling of the crickets.

It is difficult to describe cicadas to one who does not know them, and when the young Alexander Pope was translating Virgil’s line

sole sub ardenti resonant arbusta cicadis

(while the orchards echo to the harsh cicadas’ notes and mine), he fell on the expedient for his English readers of communicating the same idea by means of a more recognizable sound: “The bleating sheep with my complaints agree.”

Classical literature is full of references to cicadas as is oriental literature. They occur in the

Iliad

(where the Greek word

tettix,

T€TTL£

, is often wrongly translated as “grasshopper") and in the works of Hesiod. Theocritus says that the Greeks kept them in cages for their singing ability, and this practice is still common among the children of southern lands. In

Phaedrus

, Plato has Socrates tell how the cicadas were originally men who were touched by the muses so that they devoted their lives to singing and, forgetting to eat, died to be reborn as insects. In Taoism, cicadas became associated with

hsien

, the soul, and images of cicadas are employed when preparing a corpse for burial, to assist the soul in disengaging itself from the body after death. The importance of the cicada in the soundscape of the South, as well as the symbolism it has provoked, has been overlooked since the comparatively recent northern drift of European and American civilization.

When they become part of the farmer’s calendar, insects, like birds, arise out of the ambient soundscape to become signals for action: “May the fallows be worked for seed-time while the cicada overhead, watching the shepherds in the sun, makes music in the foliage of the trees.”