Read The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment And The Tuning Of The World Online

Authors: R. Murray Schafer

The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment And The Tuning Of The World (11 page)

From Town to City

The two great turning points in human history were the change from nomadic to agrarian life, which occurred between ten and twelve thousand years ago, and the transition from rural to urban life, which has occupied the most recent centuries. As this later development has occurred, towns have grown into cities and cities have swollen out to cover much that was formerly rural land.

In terms of the soundscape, a practical division of developing urbanization is, as in so many other matters as well, the Industrial Revolution. In the present chapter I will consider only the pre-industrial period, leaving the sequel to be taken up in Part Two of the book. A proper consideration of pre-industrial town and city life would need a much more thorough treatment than it can be given here. Town and city life diverged greatly before the Industrial and Electric revolutions began to level it, but I can only hope to hint at some of the variations, while dealing particularly with the European scene. There is a practical reason for this limitation: the accessibility of documentation.

Looking at the profile of a medieval European city we at once note that the castle, the city wall and the church spire dominate the scene. In the modern city it is the high-rise apartment, the bank tower and the factory chimney which are the tallest structures. This tells us a good deal about the prominent social institutions of the two societies. In the soundscape also there are sounds that obtrude over the acoustic horizon: keynotes, signals and soundmarks; and these types of sounds must accordingly form the principal subject of our investigation.

Making God Listen

The most salient sound signal in the Christian community is the church bell. In a very real sense it defines the community, for the parish is an acoustic space, circumscribed by the range of the church bell. The church bell is a centripetal sound; it attracts and unifies the community in a social sense, just as it draws man and God together. At times in the past it took on a centrifugal force as well, when it served to frighten away evil spirits.

Church bells appear to have been widespread in Europe by the eighth century. In England they were mentioned by The Venerable Bede at the close of the seventh century. Of their gigantic presence, Johan Huizinga writes in

The Waning of the Middle Ages:

One sound rose ceaselessly above the noises of busy life and lifted all things unto a sphere of order and serenity: the sound of bells. The bells were in daily life like good spirits, which by their familiar voices, now called upon the citizens to mourn and now to rejoice, now warned them of danger, now exhorted them to piety. They were known by their names: big Jacqueline, or the bell Roland. Every one knew the difference in meaning of the various ways of ringing. However continuous the ringing of the bells, people would seem not to have become blunted to the effect of their sound.

Throughout the famous judicial duel between two citizens of Valenciennes, in 1455, the big bell, “which is hideous to hear,” says Chastellain, never stopped ringing. What intoxication the pealing of the bells of all the churches, and of all the monasteries of Paris, must have produced, sounding from morning till evening, and even during the night, when a peace was concluded or a pope elected.

Throngs of pitched bells or carillons were especially popular in the Netherlands, where they irritated Charles Burney on his European tours. “The great convenience of this kind of music,” Burney wrote, “is that it entertains the inhabitants of a whole town, without giving them the trouble of going to any particular spot to hear it.” At a suitable distance, however, church bells could be powerfully evocative, for the strident noises of the clappers are lost and they are given a legato phrasing which wind currents or water will modulate dynamically, so that even a few simple and not very good bells can provide hours of pleasant listening. Perhaps no sound benefits more from distance and atmosphere. Church bells form a sound complement to distant hills, wrapped in blue-gray mist. Traveling a similar route to that of Charles Burney, yet keeping to the rivers and canals and avoiding the cities, Robert Louis Stevenson experienced church bells transformed in this way.

On the other side of the valley a group of red roofs and a belfry showed among the foliage. Thence some inspired bell-ringer made the afternoon musical on a chime of bells. There was something very sweet and taking in the air he played; and we thought we had never heard bells speak so intelligibly, or sing so melodiously, as these. … There is so often a threatening note, something blatant and metallic, in the voice of bells, that I believe we have fully more pain than pleasure from hearing them; but these, as they sounded abroad, now high, now low, now with a plaintive cadence that caught the ear like the burthen of a popular song, were always moderate and tunable, and seemed to fall in with the spirit of still, rustic places, like the noise of a waterfall or the babble of a rookery in spring.

Wherever the missionaries took Christianity, the church bell was soon to follow, acoustically demarking the civilization of the parish from the wilderness beyond its earshot.

f

The bell was an acoustic calendar, announcing festivals, births, deaths, marriages, fires and revolts. In Salzburg, from a small ancient hotel room, I listened to the innumerable bells ring slowly, just a shade slower than what one would expect, producing little tensions in the mind as anticipation fell a fraction of a second short of reality. And at San Miguel de Allende in Mexico I remember watching the convicts in the belfry, putting the giant bells into motion by tugging at their rims with heavy, awkward movements.

The Sound of Time

It was during the fourteenth century that the church bell was wedded to a technical invention of great significance for European civilization: the mechanical clock. Together they became the most inescapable signals of the soundscape, for like the church bell, and with even more merciless punctuality, the clock measures the passing of time audibly. In this way it differs from all previous means of telling time—water clocks, sand clocks and sundials—which were silent.

The church clock struck eleven. The air was so empty of other sounds that the whirr of the clock-work immediately before the strokes was distinct, and so was also the click of the same at their close. The notes flew forth with the usual blind obtuseness of inanimate things—flapping and rebounding among walls, undulating against the scattered clouds, spreading through their interstices into unexplored miles of space.

The clock bell had a great advantage over the clock dial, for to see the dial one must face it, while the bell sends the sounds of time rolling out uniformly in all directions. No European town was without its many clocks.

Other clocks struck eight from time to time—one gloomily from the gaol, another from the gable of an almshouse, with a preparative creak of machinery, more audible than the note of the bell; a row of tall, varnished case-clocks from the interior of a clock-maker’s shop joined in one after another just as the shutters were enclosing them, like a row of actors delivering their final speeches before the fall of the curtain; then chimes were heard stammering out the Sicilian Mariners’ Hymn; so that chronologists of the advanced school were appreciably on their way to the next hour before the whole business of the old one was satisfactorily wound up.

Clocks regulated the movements of the town with militant imperious-ness. Occasionally they rose to the status of soundmarks. (How well I remember the erratic pentatonic descent of the clock bell in the Kremlin wall—the only whimsy about the place.) Affectionately regarded by the inhabitants, some old clocks are even specifically exempted from anti-noise legislation, as is the case with the post office clock in Brantford (Ontario).

The historian Oswald Spengler believed that it was the mechanical clock that gave Europe (and particularly Germany) its sense of historical destiny.

Amongst the Western peoples, it was the Germans who discovered the mechanical

clock

, the dread symbol of the flow of time, and the chimes of countless clock towers that echo day and night over West Europe are perhaps the most wonderful expression of which a historical world-feeling is capable.

The association of clocks and church bells was by no means fortuitous; for Christianity provided the rectilinear idea of the concept of time as progress, albeit spiritual progress, with a starting point (Creation), an indicator (Christ) and a fateful conclusion (the Apocalypse). Already in the seventh century it was decreed in a bull of Pope Sabinianus that the monastary bells should be rung seven times each day, and these punctuation points became known as the canonical hours. Time is always running out in the Christian system and the clock bell punctuates this fact. Its chimes are acoustic signals, but even at a subliminal level the incessant rhythm of its ticking forms a keynote of unavoidable significance in the life of Western Man. Clocks reach into the recesses of night to remind man of his mortality.

Other Focal Points

Clocks are centripetal sounds; they unify and regulate the community. But they are not the only centripetal sounds. From early times in agricultural territories, the mill was a prominent institution at the center of town life, and its sound was as familiar as the voices of the inhabitants themselves. In Ecclesiastes (12: 3–5) the author sketches a sinister soundscape when “the women grinding the meal cease to work … when the noise of the mill is low, when the chirping of the sparrow grows faint and the songbirds fall silent.” Water wheels used for milling were recorded in Rome as far back as the first century B.C., and while many other Roman arts disappeared, only to be rediscovered in the late Middle Ages, the water mill survived, for there are frequent references to it throughout early medieval literature.

Grinding grain was not the only work done by the mills, for by the early fourteenth century there were also papermills and sawmills. By then mills also turned grinding machines for the armorers and later they ran the hammering and cutting machines of ironworks. This is why so many towns were founded on the banks of rivers or streams, where water power was available.

Where the lake became a brook, there were two or three mills. Their wheels seemed to run after each other, splashing water, like silly girls. I used to stay there long hours, watching them and throwing pebbles in the waterfalls to see them bounce and then fall again to disappear under the whirling round of the wheel. From the mills one could hear the noise of the millstones, the millers singing, children screaming, and always the squeaking of the chain over the hearth while the polenta was being stirred. I know this because the smoke coming out of the chimney always preceded the occurrence of this new, strident note in the universal concert. In front of the mills, there was a constant coming and going of sacks and flour-covered figures. Women from nearby villages came and chatted with the women of the mills while their grain was being ground. Meanwhile, the little donkeys, freed of their loads, greedily enjoyed the bran mash prepared as a treat for them on the occasion of the trips to the mills. When they finished, they started to bray, merrily stretching ears and legs. The miller’s dog barked and ran around them with playful assaults and defenses. I tell you, it was indeed a very lively scene and I couldn’t think of anything better.

To those living in the mill itself, life was never without the “patter” (Thomas Hardy’s word) of the big wheel, to which the little ones mumbled responsively, producing “a remote resemblance to the stopped diapason in an organ.” Later the mill, now equipped with a strident whistle, began to take on a more dominating aspect. We jump ahead momentarily to 1900, to a description of Dryomov, Russia, in the words of Maxim Gorky. “Awakening in the pearly gloom of an autumn dawn, Artamonov senior would hear the summoning blast of the mill whistle. Half an hour later would commence the indefatigable murmur and rustle, the accustomed, dull, but powerful din of labour.” Another sound that continued all day within earshot of most of the residents of the early town was the blacksmith. “… the sounds could not have been more distinct if they had been dropped down a deep well. From the blacksmith shop … came a

tang-tang

. A bee droomed lazily. Annie sang in her kitchen … the halter shanks, made impatient, little clinking sounds.

Tang-tang-ting-tang-tang

, went Ab’s hammer on the anvil.”

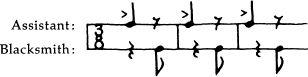

It is impossible to realize how diversified were the sounds of the blacksmith without a visit to an active forge. No museum anvil can suggest the sound, for each type of work had its own meters and accents. While on a recording expedition in Europe, we were fortunate in persuading an old Swabian blacksmith and his assistant to fire up their abandoned forge and to demonstrate the techniques. Shaping scythes consisted of a rapid series of taps, followed by slight pauses for inspection. By comparison, the shaping of horseshoes called for the assistant to strike the metal with mighty sledgehammer beats while the smith, with a little hammer for shaping, struck the metal off the beat. The meter was in three, thus: