Read The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment And The Tuning Of The World Online

Authors: R. Murray Schafer

The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment And The Tuning Of The World (15 page)

But I want to extend a thought which I had begun to develop in Part One. We have already noted how loud noises evoked fear and respect back to earliest times, and how they seemed to be the expression of divine power. We have also observed how this power was transferred from natural sounds (thunder, volcano, storm) to those of the church bell and pipe organ. I called this Sacred Noise to distinguish it from the other sort of noise (with a small letter), implying nuisance and requiring noise abatement legislation. This was always primarily the rowdy human voice. During the Industrial Revolution, Sacred Noise sprang across to the profane world. Now the industrialists held power and they were granted dispensation to make Noise by means of the steam engine and the blast furnace, just as previously the monks had been free to make Noise on the church bell or J. S. Bach to open out his preludes on the full organ.

The association of Noise and power has never really been broken in the human imagination. It descends from God, to the priest, to the industrialist, and more recently to the broadcaster and the aviator. The important thing to realize is this: to have the Sacred Noise is not merely to make the biggest noise; rather it is a matter of having the authority to make it without censure.

Wherever Noise is granted immunity from human intervention, there will be found a seat of power. The noisy clank of Watt’s original engine was maintained as a sign of power and efficiency, against his own desire to eliminate it, thus enabling the railroads to establish themselves more emphatically as the “conquerers” that I will, in a moment, let Charles Dickens describe. A glance at the sound output of any representative selection of modern machines is enough to indicate where the centers of power lie in the modern world.

| | Steam engine | 85 dBA |

| | Printing works | 87 dBA |

| | Diesel-electric generator house | 96 dBA |

| | Screw-heading machine | 101 dBA |

| | Weaving shed | 104 dBA |

| | Sawmill chipper | 105 dBA |

| | Metalwork grinder | 106 dBA |

| | Wood-planing machine | 108 dBA |

| | Metal saw | 110 dBA |

| | Rock band | 115 dBA |

| | Boiler works, hammering | 118 dBA |

| | Jet taking off | 120 dBA |

| | Rocket launching | 160 dBA |

Sound Imperialism

The historian Oswald Spengler distinguishes two phases in the development of a social movement: the cultural phase, during which the main ideas are still maturing; and the civilization phase, during which the main ideas, having matured, are legalized and transmitted abroad. Imperialism is the word used to refer to the extension of an empire or ideology to parts of the world remote from the source. It is Europe and North America which have, in recent centuries, masterminded various schemes designed to dominate other peoples and value systems, and subjugation by Noise has played no small part in these schemes. Expansion took place first on land and sea (train, tank, battleship) and then in the air (planes, rocketry, radio). The moon probes are the most recent expression of the same heroic confidence that made Western Man a world colonial power.

When sound power is sufficient to create a large acoustic profile, we may speak of it, too, as imperialistic. For instance, a man with a loudspeaker is more imperialistic than one without because he can dominate more acoustic space. A man with a shovel is not imperialistic, but a man with a jackhammer is because he has the power to interrupt and dominate other acoustic activities in the vicinity. (In this sense we note that outside workers were able to improve their position remarkably after they were in possession of tools to attract attention to themselves. No one listens to a ditchdigger.) Similarly, the growing importance of the international aviation industry can be easily assessed from the growth patterns of airport noise profiles. Western Man leaves his calling cards all over the world in the form of Western-made or Western-inspired machinery. As the factories and the airports of the world multiply, local culture is pulverized into the background. Everywhere one travels today one hears the evidence, though only in the more remote places is the incongruity immediately striking.

Increase in the intensity of sound output is the most striking characteristic of the industrialized soundscape. Industry must grow; therefore its sounds must grow with it. That is the fixed theme of the past two hundred years. In fact, noise is so important as an attention-getter that if quiet machinery could have been developed, the success of industrialization might not have been so total. For emphasis let us put this more dramatically: if cannons had been silent, they would never have been used in warfare.

The Flat Line in Sound

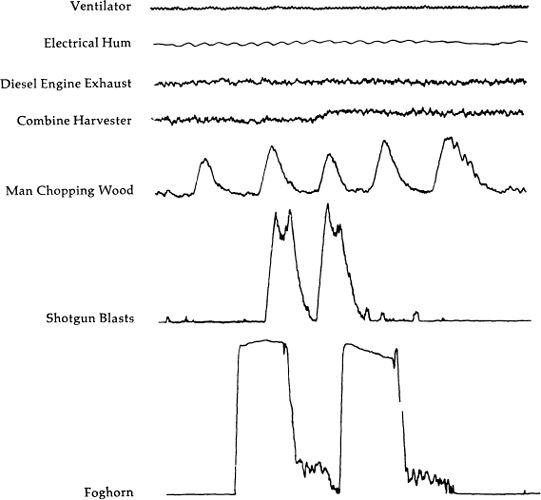

The Industrial Revolution introduced another effect into the soundscape: the flat line. When sounds are projected visually on a graphic level recorder, they may be analyzed in terms of what is called their envelope or signature. The principal characteristics of a sound envelope are the attack, the body, the transients (or internal changes) and the decay. When the body of the sound is prolonged and unchanging, it is reproduced by the graphic level recorder as an extended horizontal line.

Machines share this important feature, for they create low-information, high-redundancy sounds. They may be continuous drones (as in a generator); they may be rough-edged, possessing what Pierre Schaeffer calls a “grain” (as in mechanical sawing or filing); or they may be punctuated with rhythmic concatenations (as in weaving or threshing machines)—but in all cases it is the continuousness of the sound which is its predominating feature.

The flat continuous line in sound is an artificial construction. Like the flat line in space, it is rarely found in nature. (The continuous stridulation of certain insects like cicadas is an exception.) Just as the Industrial Revolution’s sewing machine gave us back the long line in clothes, so the factories, which operated night and day nonstop, created the long line in sound. As roads and railroads and flat-surfaced buildings proliferated in space, so did their acoustic counterparts in time; and eventually flat lines in sound slipped out across the countryside also, as the whine of the transport truck and the airplane drone demonstrate.

A few years ago, while listening to the stonemasons’ hammers on the Takht-e-Jamshid in Teheran, I suddenly realized that in all earlier societies the majority of sounds were discrete and interrupted, while today a large portion—perhaps the majority—are continuous. This new sound phenomenon, introduced by the Industrial Revolution and greatly extended by the Electric Revolution, today subjects us to permanent keynotes and swaths of broad-band noise, possessing little personality or sense of progression.

Just as there is no perspective in the lo-fi soundscape (everything is present at once), similarly there is no sense of duration with the flat line in sound. It is suprabiological. We may speak of natural sounds as having biological existences. They are born, they flourish and they die. But the generator or the air-conditioner do not die; they receive transplants and live forever.

The flat line in sound emerges as a result of an increased desire for speed. Rhythmic impulse plus speed equals pitch. Whenever impulses are speeded up beyond 20 occurrences or cycles per second, they are fused together and are perceived as a continuous contour. Increased efficiency in manufacturing, transportation and communication systems fused the im-pulses of older sounds into new sound energies of flat-line pitched noise. Man’s foot sped up to produce the automobile drone; horses’ hooves sped up to produce the railway and aircraft whine; the quill pen sped up to produce the radio carrier wave, and the abacus sped up to produce the whirr of computer peripherals.

Graphic level recordings of typical flat-line and impact sounds

.

Henri Bergson once asked how we should know about it if some agent suddenly doubled the speed of

all

events in the universe? Quite simply, he replied, we should discern a great loss in the richness of experience. Even as Bergson wrote, this was happening, for as discrete sounds gave way to flat lines, the noise of the machine became “a narcotic to the brain,” and listlessness increased in modern life.

The function of the drone has long been known in music. It is an anti-intellectual narcotic. It is also a point of focus for meditation, particularly in the East. Man listens differently in the presence of drones, and the importance of this change in perception is becoming evident in the West.

The flat line in sound produces only one embellishment: the glissando—that is, as the revolutions increase the pitch gradually rises, and as they decrease the pitch descends. Then flat lines become curved lines. But they are still without sudden surprises. When flat lines become jerky or dotted or looping lines—the machinery is falling apart.

Another type of curve produced by the flat line is the Doppler effect, which results when a sound is in motion at sufficient velocity to cause a bunching up of the sound waves as the sound approaches an observer (resulting in a rise in pitch) and an elongation of the sound waves as the sound recedes (resulting in a lowering of pitch). There are certainly Doppler effects in nature (the flight of a bee, for instance, or the galloping of horses) but only after the new speeds of the Industrial Revolution did the effect become conspicuous enough to be “discovered.” Christian Johann Doppler (1803–53) formulated the explanation of the effect to which he has bequeathed his name in a work entitled Ü

ber das Farbige Licht der Doppelsterne

, where he applied the principle to light waves. But Doppler acknowledged that he worked by analogy from sound to light.

Some sounds move in space, some do not; and we may move some sounds by carrying them with us. But which sound attracted Doppler’s ear? It could only have been the railway. Although he does not mention this, we do know trains were used to verify the Doppler effect. About 1845 “musically trained observers were stationed along the tracks of the Rhine Railroad between Utrecht and Maarsen in Holland and listened to trumpets played in a railway car as it sped past. From the known pitch of the trumpet and the apparent pitch of the approaching and receding tones, the speed of the railway car was estimated with fairly good accuracy.”

The Lore of Trains

The first railway was the Stockton and Darlington run in England (1825), designed to carry coal from the mines to the waterways. It proved so immediately successful that within a few years Britain was covered with a railway network. Dickens described the new sound in 1848:

Night and day the conquering engines rumbled at their distant work, or, advancing smoothly to their journey’s end, and gliding like tame dragons into the allotted corners grooved out to the inch for their reception, stood bubbling and trembling there, making the walls quake, as if they were dilating with the secret knowledge of great powers yet unsuspected in them, and strong purposes not yet achieved.

From England the railway system fanned out quickly across Europe and the world. France had a railway by 1828 as did the U.S.A., Ireland by 1834, Germany by 1835, Canada by 1836, Russia by 1837, Italy by 1839, Spain by 1848, Norway and Australia by 1854, Sweden by 1856 and Japan by 1872.

The train conquered the world with a minimum of opposition. Dickens didn’t like it: “Louder and louder yet, it shrieks and cries as it comes tearing on resistless to the goal.” Neither did Wagner, and although the Bavarian College of Medicine protested in 1838 that the speed with which trains traveled would undoubtedly cause brain damage, the trains remained and the tracks multiplied.

Of all the sounds of the Industrial Revolution, those of trains seem across time to have taken on the most attractive sentimental associations. J. M. W. Turner’s celebrated painting

Rain, Steam and Speed

(1844), with its locomotive thrusting down diagonally on the spectator, was the first lyric inspired by the steam engine. It was a painter, too, who caught the next change in the epic of the railroads. By 1920 the main lines of Europe (though not of England and North America) were being electrified, and the change is recorded in de Chirico’s wistful landscapes, where silent smoke-puffing trains pass out of sight in the extreme distance.

By comparison with the sounds of modern transportation, those of the trains were rich and characteristic: the whistle, the bell, the slow chuffing of the engine at the start, accelerating suddenly as the wheels slipped, then slowing again, the sudden explosions of escaping steam, the squeaking of the wheels, the rattling of the coaches, the clatter of the tracks, the thwack against the window as another train passed in the opposite direction—these were all memorable noises.