The Story of Rome (32 page)

One day he noticed that stands were being put up round the ground where public games were to be held. These stands were for the rich, who could afford to pay for them. As they took up a great deal of room, and would spoil the view of many of the poorer folk, Gaius begged that they might be removed. But his request was refused, and he himself was ridiculed by his enemies.

Then Gaius took the matter into his own rash hands.

The evening before the games were to take place he ordered workmen to pull down the stands and level the ground, so that on the morrow rich and poor would be forced to stand side by side if they were to see the games.

Soon after this the election of tribunes took place, and although Gaius had done much for the sake of the people's welfare, they showed no gratitude. In 121

B

.

C

.

he was not again chosen as their tribune.

What was even more serious was that the Consuls for the year, Fabius Maximus and Opimius, were leaders of the Optimates, so that the enemies of Gaius were now powerful enough to attack him publicly.

First they worked upon the superstitious fears of the populace. They reminded the people that the site of Carthage had been cursed, yet here were Gracchus and his friends venturing to build a new city on the very spot.

Omens, too, had been ignored. His enemies told how the boundary stones of the new city and the measuring poles had been torn out of the ground by wild beasts and carried away. Such things, they said, must portend the wrath of gods.

Thus they paved the way for the blow which they hoped to inflict upon Gracchus. For they now called the tribes together and asked them to repeal the law permitting the building and colonising of Carthage. The people themselves had passed the law only the year before.

Gracchus and his friends determined to fight against the repeal of this law. But while Gracchus hoped to avoid violence, his friends were ready to use force to gain their ends.

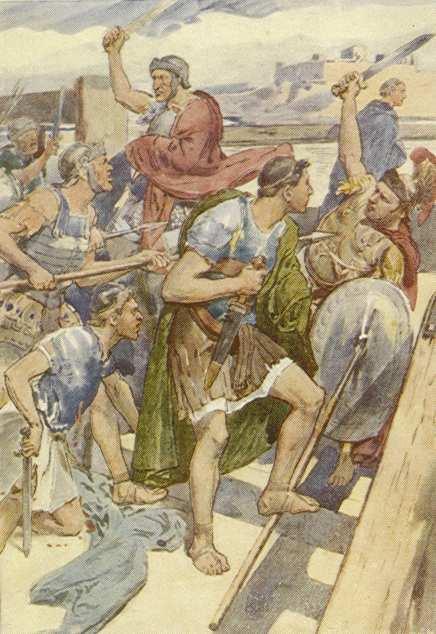

The anger of both parties was roused, and lest one side should take advantage of the other, both took up their position on the Capitol, meaning to spend the night on the hill. But it was unlikely to be a quiet night. Any moment a spark might set the flames of anger alight.

As Gracchus walked up and down, speaking to one and another, the servant of the Consul came from the temple carrying away part of the sacrifice that had just been offered, and shouting in a rude manner to the people to leave room for him to pass.

When he drew near to Gracchus the people imagined that he threatened their leader.

At once the mob was in a panic. Some one cried that the life of Gaius was in danger, and in a moment the insolent servant was killed.

Gracchus was deeply grieved that one of his party should have been so rash. It gave to his enemies the very opportunity which they wished.

The Senate, indeed, showed great horror at such a deed of violence, and ordered the body of the dead man to be held up to the people. "This is how Gracchus and his friends treat the poor," was what the Senate wished the people to think. It then denounced Gaius and his party as enemies of the republic.

After this both the parties left the Capitol, Gracchus and his friends taking up their position on the Aventine hill early the following morning.

Before he left home Gaius refused to wear armour, but put on his gown as though he were simply going to an Assembly of the people. He did, however, wear a short dagger beneath his tunic.

As he reached the threshold his wife rushed after him and caught him with one hand, while with the other she clasped one of her children.

"You go now," she said to her husband, "to expose your body to the murderers of Tiberius, unarmed, indeed, and rightly so, choosing rather to suffer the worst of injuries than do the least yourself."

But Gaius would listen to no more. Gently he withdrew himself from her hold, and stricken with grief, his wife fell to the ground.

When Opimius, the Consul, heard of the gathering on the Aventine, he declared that it was an act of war to seize a position within the city and hold it against the Senate. He ordered it to be proclaimed that he would give its weight in gold to any one who brought him the head of Gaius Gracchus. Then, with a troop of soldiers and archers, Opimius prepared to march against those whom he had declared rebels.

The leader of the mob, for indeed it was little else, was Fulvius, who had been both tribune and Consul.

He now sent his young son, of eighteen years of age, to propose to the Senate that peace should be arranged without having recourse to arms.

The lad was sent back to say that the rebels must disperse, and Gracchus and Fulvius appear before the Senate to answer for what they had done, before it was possible to think of terms.

Gracchus would have agreed to do this, but Fulvius refused to give way, and sent his son back to the Senate with other proposals.

This time the messenger was not sent back, but was kept prisoner by Opimius, who without further delay went forward toward the Aventine hill.

Fulvius had not courage to face the troops of the Consul, and he fled and hid himself in a bath, from which he was soon dragged ignominiously, and put to death.

Gracchus did not attempt to lead his followers against the soldiers. He may have felt it was hopeless to do so.

His friends urged him to escape, but he, it is said, first fell upon his knees, and in the bitterness of his heart besought the goddess Diana to punish the fickle, ungrateful people of Rome by sending them into unending slavery.

Then he fled down the hill toward the river Tiber, followed by two of his most faithful friends and a slave.

One of his friends fell and sprained his foot. He quickly rose and faced the pursuers, resolved to hinder them as long as might be. But he was soon put to death.

At the bridge that crossed the Tiber the other friend stopped. Here it would be possible, he thought, to hold the enemy at bay for a time. Perhaps as he stood at his post he thought of the old Roman hero, Horatius Cocles, who had so nobly held the bridge against the foes of Rome. But ere long he too was slain.

Here it would be possible, he thought, to hold the enemy at bay.

Then Gaius, knowing that all hope was at an end, called for a horse. But his enemies were watching, and no one dared to answer his request.

Yet taken alive he would never be! So with desperate speed he ran on until he reached a little grove, which was consecrated to the Furies, and here for a few brief moments he was hidden from his pursuers. Then in a stern voice he bade his slave, who was now alone with him, to kill him before he was discovered by his enemies.

His slave obeyed, and, faithful to the end, slew himself as well as his master.

Here in the grove his enemies found the body of Gaius Gracchus, covered by that of his devoted slave.

The head of the dead man was cut off, and to increase its weight was filled with lead. This was done, it is told, by one who was once his friend. But this we cannot easily believe. It was, however, taken to the Consul, who gave for it the promised reward—its weight in gold.

The body of Gaius was then dragged through the streets, and thrown into the Tiber.

And Cornelia, the mother of the Gracchi?

She bore the loss of her two sons as she had borne all the disasters of her life, with an undaunted spirit.

Her friends marvelled to hear her speak of her sons with no outward sign of grief, but Cornelia was too proud of the service they had done for Rome to weep. Yet she left the city and lived in retirement, for, with all her fortitude, she could not bear to meet those who had approved of the murder of her sons.

In after years the Romans learned to be ashamed of their treatment of the Gracchi, and in reverence for the noble matron who had borne them they erected a bronze statue in the Forum. On it were inscribed these simple words: "To Cornelia, the mother of the Gracchi."

CHAPTER LXXXIII

The Gold of Jugurtha

J

UGURTHA

was king, King of Numidia. It is true that he had stolen his kingdom, or at least the greater part of it, from his two young cousins, the grandsons of Masinissa, yet he was safely seated on the throne.

One of the princes Jugurtha had murdered, the other had escaped to Rome and claimed her help.

But Jugurtha was rich, and he knew that at Rome gold could purchase what he wished. So now he sent large sums of money to some of the senators, and these could not resist the wealth that was offered to them.

In this way justice went awry, to the bewilderment of Adherbal the prince, for the senators who were bribed, voted that Jugurtha should keep the wealthiest and strongest part of Numidia, while Adherbal might claim what was left.

But even this was not enough to satisfy the ambition of the king. He now wished to wrest from the prince even the small dominion that had been allotted to him.

Again and again Adherbal appealed to Rome, but her hands were filled with the gold of the tyrant, and she would do nothing to help his victim.

At length Jugurtha besieged his cousin in his capital town of Cirta.

The prince was not strong enough to defy his enemy, and there was no choice but to surrender, and this Adherbal did, on condition that his life and that of the inhabitants should be spared.

But it was vain to trust Jugurtha. He cared little for the promise he had given, and no sooner had the prince left the city than his cousin ordered that he should be put to death, while the inhabitants, Italians as well as Numidians, were also slain.

The treachery of Jugurtha was known in Rome, but it was ignored. How could it be otherwise when those who should have rebuked and punished him were spending his money.

But among the tribunes there was one man, whose hands were clean, and he, in the Assembly of the people, denounced the nobles for taking bribes and allowing Jugurtha to go on his treacherous way unchecked.

So earnest were the words of Memmius that the people were roused, and the Senate dared no longer refuse to call the tyrant to account. War was therefore declared against the King of Numidia in 112

B

.

C

.

But it was useless to send an army to Africa unless the officers were honourable men.

Bestia, the Consul, when he reached the enemy's country, did at first attack and capture several towns, as well as take many of Jugurtha's men prisoners.

Then, all at once, the activities of the Consul came to an end. He fought no more against the enemy. For Bestia had been offered the gold of Jugurtha and had accepted it, and the tyrant was again left to use his power as he chose.

At home, however, Memmius did not scruple to expose the conduct of Bestia, and to denounce it as unworthy of a Roman. His persistence won the day.

In 110

B

.

C

.

Jugurtha was brought to Rome under a safe conduct, that he might give evidence against those who had accepted his gold.

But even now the king still found some willing to handle his money, and justice was delayed, if it was not altogether turned aside.

One of the Consuls meanwhile wished to depose Jugurtha and make a young prince King of Numidia.

When Jugurtha heard this he did not hesitate to order his slave to go at once to put his rival to death.

Such a deed was more than Rome could tolerate, and Jugurtha found it necessary to escape from the city.

The Senate saw that the war in Africa must be carried on. But to do so with any hope of success it was necessary to find a general who would scorn to take a bribe.

In the summer of 109

B

.

C

.

such a man was found in the Consul Metellus, who was now sent to Numidia as commander of the army. With him, as his lieutenant or legate, he took Gaius Marius, of whose boyhood I must tell you.

CHAPTER LXXXIV

Gaius Marius Wins the Notice of Scipio Africanus

G

AIUS

Marius was born in 157

B

.

C

.

His parents were humble folk, who had to work for their daily bread.

Marius grew up knowing nothing of the indolence and luxury that surrounded so many Roman youths of noble birth.

His boyhood was lived in a mountain village, where, if his training made him rough and uncouth, it also taught him to endure hardness, and to eat and drink only what was needful for his health. It was many long years before Marius knew anything of the polished manners and indulgent ways of the city.

From his youth Gaius Marius was bold and active. As he grew older, his temper would often flash out in ungovernable passion when there was little to provoke it.

The lad first served as a soldier under the younger Scipio Africanus. He was used to frugal fare, and to him the simple manner in which Scipio insisted that his soldiers should live seemed only natural.