The Story of the Romans (Yesterday's Classics) (14 page)

Fabius was now obliged to share his command with another general, who did not like his plan of avoiding an open battle. This general advanced against Hannibal and began to fight; but he would have paid dearly for his imprudence, had not Fabius come to his rescue just in time to save him.

By pursuing these cautious tactics, which have since often been called the "Fabian policy," Fabius prevented Hannibal from gaining any great advantage. But when his time of office was ended, his successors, the consuls Varro and Æmilius, thinking they would act more wisely, and end the war, again ventured to fight the Carthaginians.

The battle took place at Cannæ, and the Romans were again defeated, with very great loss. Æmilius fell, but not till he had sent a last message to Rome, bidding the people strengthen their fortifications, and acknowledging that it would have been far wiser to have pursued the Fabian policy.

So many Romans were slain on this fatal day at Cannæ that Hannibal is said to have sent to Carthage one peck of gold rings, taken from the fingers of the dead knights, who alone wore them.

When the tidings of the defeat came to Rome, the sorrowing people began to fear that Hannibal would march against them while they were defenseless, and that he would thus become master of the city. In their terror, they again appealed to Fabius, who soon restored courage and order, called all the citizens to arms, and drilled even the slaves to fight.

Hannibal, in the mean while, had gone to Capua, where he wished to spend the winter, and to give his men a chance to recruit after their long journey and great fatigues. The climate was so delightful, the food so plentiful, and the hot baths so inviting, that many of the Carthaginians grew fat and lazy, and before they had spent many months there, they were no longer able to fight well.

Ever since then, when people think too much of ease, and not enough of duty, they are said to be "languishing in the delights of Capua."

The Inventor Archimedes

H

IERO

,

King of Syracuse, died shortly after the battle of Cannæ. He had helped the Romans much, but his successors soon made an alliance with the Carthaginians, and declared war against Rome.

The Romans, however, had taken new courage from the welcome news that Hannibal had decided upon going to Capua, instead of marching straight on to Rome. As soon as some of the new troops could be spared, therefore, they were sent over to Sicily, under the command of Marcellus, with orders to besiege Syracuse. This was a very great undertaking, for the city was strongly fortified, and within its walls was Archimedes, one of the most famous mathematicians and inventors that have ever been known.

He had discovered that even the heaviest weights could be handled with ease by means of pulleys and levers; and he is said to have exclaimed: "Give me a long enough lever and a spot whereon to rest it, and I will lift the world."

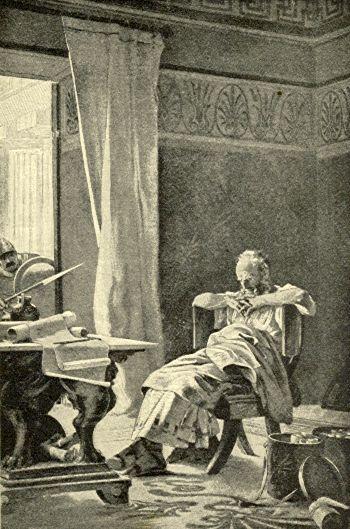

Archimedes

Archimedes made use of his great talents to invent all sorts of war engines. He taught the Syracusans how to fashion stone catapults of great power, and large grappling hooks which swung over the sea, caught the enemy's vessels, and overturned them in the water. He is also said to have devised a very clever arrangement of mirrors and burning glasses, by means of which he could set fire to the Roman ships. To prevent the Syracusan ships from sinking when they had water in their holds, he invented a water screw which could be used for a pump.

Thanks to the skill of Archimedes, the Syracusans managed to hold out very long; but finally the Romans forced their way into the town. They were so angry with the people for holding out so long that they plundered the whole city, and killed many of the inhabitants.

A Roman soldier rushed into the house where Archimedes was sitting, so absorbed in his calculations that he was not even aware that the city had been taken. The soldier, not knowing who this student was, killed Archimedes as he was sitting in front of a table loaded with papers.

Marcellus, the Roman general, had given orders that the inventor should be spared, and was very sorry to hear that he was dead. To do Archimedes honor, he ordered a fine funeral, which was attended by Romans and Syracusans alike.

In the mean while, Hannibal was beginning to lose ground in Italy; and the Carthaginians who were left in Spain had been obliged to fight many battles. Their leader was Hasdrubal, the brother of Hannibal, while the Romans were commanded by the two Scipios.

These two generals were at last both unlucky; but their successor, another Scipio, defeated the Carthaginians so many times that the whole country became at last a Roman province. Escaping from Spain, Hasdrubal prepared to follow the road his brother had taken, so as to join him in southern Italy.

He never reached Hannibal, however; for after crossing the Alps he was attacked and slain, with all his army. The Romans who won this great victory then hastened south and threw Hasdrubal's head into his brother's camp; and this was the first news that Hannibal had of the great disaster.

All the luck in the beginning of this war had been on the side of the Carthaginians. But fortune had now forsaken them completely; and Hannibal, after meeting with another defeat, went back with his army to Carthage, because he heard that Scipio had come from Spain to besiege the city.

The country to the west of Carthage, called Numidia, was at this time mostly divided between two rival kings. One of them, Masinissa, sent his soldiers to help Scipio as soon as he crossed over to Africa, and the Romans could not but admire the fine horsemanship of these men. They were the ancestors of the Berbers, who live in the same region to-day and are still fine riders.

Syphax, the rival of Masinissa, joined the Carthaginians, who promised to make him king of all Numidia if they succeeded in winning the victory over their enemies. With their help he fought three great battles against the Romans, but in each one he was badly defeated, and in the last he was made prisoner.

After Hannibal came, he soon met the invaders near Zama, and a great battle was fought, in which Scipio and Masinissa gained the victory. In their despair, the Carthaginians proposed to make peace. The Romans consented, and the Second Punic War ended, after it had raged about seventeen years.

On his return to Rome, Scipio was honored by receiving the surname of Africanus, and by a grand triumph, in which Syphax followed his car, chained like a slave. But although the Romans cheered Scipio wildly, and lavished praises upon him, they soon accused him of having wrongfully taken possession of some of the gold he had won during his campaigns.

This base accusation was brought soon after Scipio had helped to win some great victories in Asia, of which you will soon hear; and it made him so angry that he left Rome forever. He withdrew to his country house in Campania, a part of Italy to the southeast of Rome.

Here he remained as long as he lived; and when he died he left orders that his bones should not rest in a city which had proved so ungrateful as Rome.

The Roman Conquests

Y

OU

might think that the Romans had all they could do to fight the Carthaginians in Spain, Italy, and Africa; but even while the Second Punic War was still raging, they were also obliged to fight Philip V., King of Macedon.

As soon as the struggle with Carthage was ended, the war with Philip was begun again in earnest. The army was finally placed under the command of Flamininus, who defeated Philip, and compelled him to ask for peace. Then he told the Greeks, who had long been oppressed by the Macedonians, that they were free from further tyranny.

This announcement was made by Flamininus himself at the celebration of the Isthmian Games; and when the Greeks heard that they were free, they sent up such mighty shouts of joy that it is said that a flock of birds fell down to the earth quite stunned.

To have triumphed over the Carthaginians and Macedonians was not enough for the Romans. They had won much land by these wars, but were now longing to get more. They therefore soon began to fight against Antiochus, King of Syria, who had been the ally of the Macedonians, and now threatened the Greeks.

Although Antiochus was not a great warrior himself, he had at his court one of the greatest generals of the ancient world. This was Hannibal, whom the Carthaginians had exiled, and while he staid there he once met his conqueror, Scipio, and the two generals had many talks together.

On one occasion, Scipio is said to have asked Hannibal who was the greatest general the world had ever seen.

"Alexander!" promptly answered Hannibal.

"Whom do you rank next?" continued Scipio.

"Pyrrhus."

"And after Pyrrhus?"

"Myself!" said the Carthaginian, proudly.

"Where would you have placed yourself if you had conquered me?" asked Scipio.

"Above Pyrrhus, and Alexander, and all the other generals!" Hannibal exclaimed.

If Antiochus had followed Hannibal's advice, he might, perhaps, have conquered the Romans; but although he had a much greater army than theirs, he was soon driven out of Greece, and defeated in Asia on land and sea by another Scipio (a brother of Africanus), who thus won the title of Asiaticus.

Then the Romans forced Antiochus to give up all his land in Asia Minor northwest of the Taurus Mountains, and also made him agree to surrender his guest, Hannibal. He did not keep this promise, however; for Hannibal fled to Bithynia, where, finding that he could no longer escape from his lifelong enemies, he killed himself by swallowing the poison contained in a little hollow in a ring which he always wore.

The Romans had allowed Philip to keep the crown of Macedon on condition that he should obey them. He did so, but his successor, Perseus, hated the Romans, and made a last desperate effort to regain his freedom. The attempt was vain, however, and he was finally and completely defeated at Pydna.

Perseus was then made a prisoner and carried off to Italy, to grace the Roman general's triumph; and Macedon (or Macedonia), the most powerful country in the world under the rule of Alexander, was reduced to the rank of a Roman province, after a few more vain attempts to recover its independence.

Destruction of Carthage

W

HILE

Rome was thus little by little extending its powers in the East, the Carthaginians were slowly recovering from the Second Punic War, which had proved so disastrous for them. The Romans, in the mean while, felt no great anxiety about Carthage, because their ally, Masinissa, was still king of Numidia, and was expected to keep the senate informed of all that was happening in Africa.

But after the peace had lasted about fifty years, and Carthage had got over her losses, and again amassed much wealth, some of the Romans felt quite sure that the time would come when the contest would be renewed. Others, however, kept saying that Carthage should be entirely crushed before she managed to get strength enough to fight.

One man in Rome was so much in favor of this latter plan that he spoke of it on every opportunity. This was Cato, the censor, a stern and proud old man, who ended every one of the speeches which he made before the senate, by saying: "Carthage must be destroyed!"

He repeated these words so often and so persistently that by and by the Romans began to think as he did; and they were not at all sorry when the King of Numidia broke the peace and began what is known in history as the Third Punic War.

The Carthaginians, worsted in the first encounter, were very anxious to secure peace. Indeed, they were so anxious that they once gave up all their arms at the request of Rome. But after making them give up nearly all they owned, the Romans finally ordered them to leave their beautiful city so that it could be destroyed, and this they refused to do.

As peace was not possible, the Carthaginians then made up their minds to fight bravely, and to sell their liberty only with their lives. Their arms having been taken away from them, all the metal in town was collected for new weapons. Such was the love of the people for their city that the inhabitants gave all their silver and gold for its defense, to make the walls stronger.

Not content with giving up their jewelry, the Carthaginian women cut off their long hair to make ropes and bowstrings, and went out with their oldest children to work at the fortifications, which were to be strengthened to resist the coming attack. Every child old enough to walk, fired by the example of all around him, managed to carry a stone or sod to help in the work of defense.

The siege began, and, under the conduct of Hasdrubal, their general, the Carthaginians held out so bravely that at the end of five years Carthage was still free. The Romans, under various commanders, vainly tried to surprise the city, but it was only when Scipio Æmilianus broke down the harbor wall that his army managed to enter Carthage.

The Romans were so angry at the long resistance of their enemies that they slew many of the men, made all the women captives, pillaged the town, and then set fire to it. Next the mighty walls were razed, and Carthage, the proud city which had rivaled Rome for more than a hundred years, was entirely destroyed.