The Story of the Romans (Yesterday's Classics) (18 page)

Pompey's Conquests

A

S

Pompey had claimed all the credit of the victory over the revolted slaves, you can readily understand that Crassus did not love him very much. Both of these men were ambitious, and they both strove to win the favor of the Romans. They made use of different means, however; for Pompey tried to buy their affections by winning many victories, while Crassus strove to do the same by spending his money very freely.

Crassus was at this time a very rich man. He gave magnificent banquets, kept open house, and is said to have entertained the Romans at ten thousand public tables, which were all richly spread. He also made generous gifts of grain to all the poor, and supplied them with food for several months at a time.

In spite of this liberality, the people seemed to prefer Pompey, who, soon after defeating the slaves, made war against the pirates that infested the Mediterranean Sea. These pirates had grown very numerous, and were so bold that they attacked even the largest ships. They ruthlessly butchered all their common prisoners, but they made believe to treat the Roman citizens with the greatest respect.

If one of their captives said that he was a Roman, they immediately began to make apologies for having taken him. Then they stretched a plank from the side of the ship to the water, and politely forced the Roman to step out of the vessel and into the sea.

The pirates also robbed all the provision ships on their way from Sicily to Rome; and, as a famine threatened, the Romans sent Pompey to put an end to these robberies. Pompey obeyed these orders so well that four months later all the pirate ships were either captured or sunk, and their crews made prisoners or slain.

Pompey knew that the pirates were enterprising men, so he advised the senate to send them out to form new colonies. This good advice was followed, and many of these men became in time good and respectable citizens in their new homes.

As Pompey had been so successful in all his campaigns, the Romans asked him to take command of their armies when a third war broke out with their old enemy Mithridates, King of Pontus in Asia Minor.

With his usual good fortune, Pompey reached the scene of conflict just in time to win the final battles, and to reap all the honors of the war. We are told that he won a glorious victory by taking advantage of the moonlight, and placing his soldiers in such a way that their shadows stretched far over the sand in front of them. The soldiers of Mithridates, roused from sound slumbers, fancied that giants were coming to attack them, and fled in terror.

As for Mithridates, he preferred death to captivity, and killed himself so that he would not be obliged to appear in his conqueror's triumph.

Pompey next subdued Syria, Phœnicia, and Judea, and entered Jerusalem. Here some of the Jews held out in their temple, which was taken only after a siege of three months. In spite of their entreaties, Pompey went into the Holy of Holies,—a place where even the high priest ventured only once a year; and we are told that he was punished for this sacrilege by a rapid decline of his power.

All the western part of Asia was now under Roman rule; and, when Pompey came back to Rome, he brought with him more than three million dollars' worth of spoil.

Wealth of all kinds had been pouring into Rome for so many years that it now seemed as if these riches would soon cause the ruin of the people. The rich citizens formed a large class of idlers and pleasure seekers, and they soon became so wicked that they were always doing something wrong.

The Conspiracy of Catiline

W

HILE

Pompey was away in the East, a few young Romans, who had nothing else to do, imagined that it would be a fine thing to murder the consuls, abolish all the laws, plunder the treasury, and set fire to the city. They therefore formed a conspiracy, which was headed by Catiline, a very wicked man.

The reason why Catiline encouraged the young idlers to such crimes was that he had spent all his own money, had run deeply into debt, and wished to find some way to procure another fortune to squander on his pleasures.

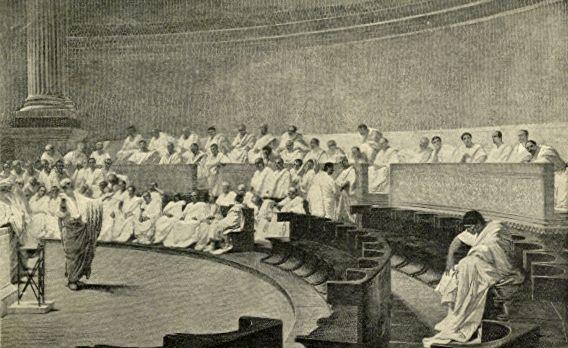

Fortunately for Rome, this conspiracy was discovered by the consul Cicero, the most eloquent of all the Roman orators. He revealed the plot to the senate, but Catiline had the boldness to deny all knowledge of it.

Cicero then went on to denounce the traitor in one of those eloquent speeches which are read by all students of the Latin language. Catiline, however, indignantly left the senate hall, and, rushing out of the city, went to join the army of rebels that was awaiting him. But the conspirators who staid in the city were arrested and put to death by order of Cicero and the senate.

Cicero denouncing Catiline

In the mean while, an army had been sent out against Catiline, who was defeated and killed, with the greater part of his soldiers. The Romans were so grateful to Cicero for saving them from the threatened destruction that they did him much honor, and called him the "Father of his Country."

Shortly after this event, and the celebration of Pompey's new triumph, the old rivalry between him and Crassus was renewed. They were no longer the only important men in Rome, however; for Julius Cæsar was gradually coming to have more and more power.

This Julius Cæsar was one of the greatest men in Rome. He was clever and cool, and first used his influence to secure the recall of the Romans whom Sulla had banished. As Cæsar believed in gentle measures, he had tried to persuade the senate to spare the young men who had plotted with Catiline. But he failed, owing to Cicero's eloquence, and thus first found himself opposed to this able man.

Cæsar was fully as ambitious as any of the Romans, and he is reported to have said, "I would rather be the first in a village than the second in Rome!" In the beginning of his career, however, he clearly understood that he must try and make friends, so he offered his services to both Pompey and Crassus.

Little by little Cæsar persuaded these two rivals that it was very foolish in them to fight, and finally induced them to be friends. When these three men had thus united their forces, they felt that they held the fortunes of Rome in their hands, and could do as they pleased.

They therefore formed a council of three men, or the Triumvirate, as it is called. Rome, they said, was still to be governed by the same officers as before; but they had so much influence in Rome that the people and senate did almost everything that the Triumvirate wished.

To seal this alliance, Cæsar gave his daughter Julia in marriage to Pompey. Then, when all was arranged according to his wishes, Cæsar asked for and obtained the government of Gaul for five years. To get rid of Cicero, Clodius, a friend of the Triumvirate, revived an old law, whereby any person who had put a Roman citizen to death without trial was made an outlaw. Clodius argued that Cicero had not only caused the death of the young Romans in Catiline's conspiracy, but had even been present at their execution.

Cicero could not avoid the law, so he fled, and staid away from Rome for the next sixteen months. This was a great trial to him, and he complained so much that he was finally recalled. The people, who loved him for his eloquence, then received him with many demonstrations of joy.

Cæsar's Conquests

I

N

the mean while, Cæsar had gone to govern Gaul, and was forcing all the different tribes to recognize the authority of Rome. He fought very bravely, and wrote an account of these Gallic wars, which is so simple and interesting that it is given to boys and girls to read as soon as they have studied a little Latin.

Cæsar not only subdued all the country of Gaul, which we now know as France, but also conquered the barbarians living in Switzerland and in Belgium.

Although he was one of the greatest generals who ever lived, he soon saw that he could not complete these conquests before his time as governor would expire. He therefore arranged with his friends Crassus and Pompey, that he should remain master of Gaul for another term, while they had charge of Spain and Syria.

The senate, which was a mere tool in the hands of these three men, confirmed this division, and Cæsar remained in Gaul to finish the work he had begun. But Pompey sent out an officer to take his place in Spain, for he wished to remain in Rome to keep his hold on the people's affections.

As Crassus liked gold more than anything else, he joyfully hastened off to Syria, where he stole money wherever he could, and even went to Jerusalem to rob the Temple. Shortly after this, he began an unjust war against the Parthians. They defeated him, killed his son before his eyes, and then slew him too.

We are told that a Parthian soldier cut off the Roman general's head and carried it to his king. The latter, who knew how anxious Crassus had always been for gold, stuffed some into his dead mouth, saying:

"There, sate thyself now with that metal of which in life thou wert so greedy."

You see that even a barbarian has no respect whatever for a man who is so base as to love gold more than honor.

Cæsar's Soldiers

While Crassus was thus disgracing himself in Asia, Cæsar was daily winning new laurels in Gaul. He had also invaded Britain, whose shores could be seen from Gaul on very clear days.

Although this island was inhabited by a rude and war-like people, it had already been visited by the Phœnicians, who went there to get tin from the mines in Cornwall.

Cæsar crossed the Channel, in small ships, at its narrowest part, between the cities of Calais and Deal. When the Britons saw the Romans approaching in battle array, they rushed down to the shore, clad in the skins of the beasts they had slain. Their own skins were painted blue, and they made threatening motions with their weapons as they uttered their fierce war cry.

But in spite of a brave resistance, Cæsar managed to land, and won a few victories; however, the season was already so far advanced that he soon returned to Gaul. The next year he again visited Britain, and defeated Cassivelaunus, a noted Briton chief.

This victory ended the war. The Britons pretended to submit to the Roman general, and agreed to pay a yearly tribute. So Cæsar departed to finish the conquest of Gaul; but he carried off with him a number of hostages, to make sure the people would keep the promises they had made.

As the news of one victory after another came to Rome, Cæsar's influence with the people grew greater every day. Pompey heard all about this, and he soon became very jealous of his friend's fame. As his wife, Julia, had died, he no longer felt bound to Cæsar by any tie, so he began to do all he could to harm his absent colleague.

As to the soldiers, they were all devoted to their general, because he spoke kindly to them, knew them by name, and always encouraged them by word and example, in camp and on the march.

The Crossing of the Rubicon

T

HE

news of Pompey's hostility was soon conveyed to Cæsar, who therefore tried harder than ever to keep in the good graces of the Romans, and asked to be named consul.

Cæsar had now been governor of Gaul almost nine years. In that short space of time he managed to subdue eight hundred towns and three hundred tribes; and he had fought against more than three million soldiers. His services had been so great that Pompey did not dare oppose his wishes openly, lest the people should be angry.

Pompey, however, was very anxious that his rival should come to Rome only as a private citizen. He therefore bribed a man to oppose Cæsar's election as consul, on the plea that it was against the law to elect any man who was absent from the city.

Then, as Cæsar staid in Gaul, Pompey advised the senate to recall two of his legions; but even when parted from him, these men never forgot the general they loved, and remained true to him.

As all the attempts to hinder Cæsar and lessen his glory had been vain, Pompey now fancied that it would be a good plan to make him come back to Rome, where he would not have an army at his beck and call. So the senate sent out the order that Pompey wished; but, instead of starting out for Italy alone, Cæsar came over the Alps at the head of his army. The great general was determined to get the better of his rival, arms in hand, if he could not secure what he wished more peaceably.