The Sugar King of Havana (10 page)

Read The Sugar King of Havana Online

Authors: John Paul Rathbone

By the 1910s, the Lobos were a well-established presence in Havana. After Galbán retired in 1914 to return to the Canary Islands, Heriberto became president of the company, which was renamed Galbán Lobo shortly after. He and Virginia invited their Caracas relatives to stay, adding other Venezuelan touches to their life in Havana, such as the traditional Christmas meal of

hallaca

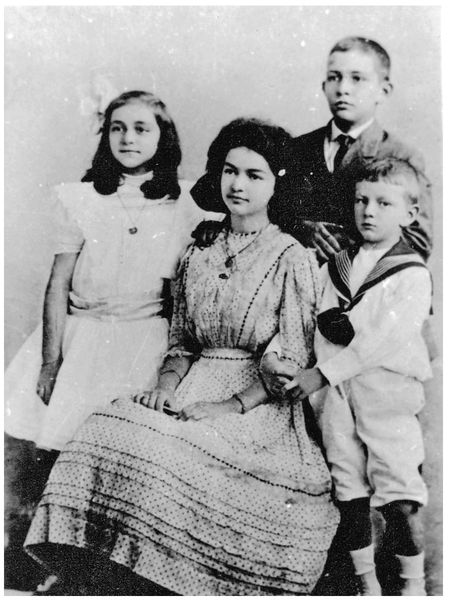

, a mixture of pork, beef, capers, raisins, and olives packed into a cornmeal mush, wrapped in plantain leaves. They had two more children, Jacobo and Helena, fussed over by nannies and governesses, as was the norm. Leonor grew into a striking teenager; an accomplished pianist, she was Virginia and Heriberto’s favorite. Julio apparently vied for his parents’ attention; although he had a happy childhood, this may have been an early spur to his ambition. Jacobo was the mischievous younger son. Although he is scowling in the photograph, his humor and charm could make his elder brother look sullen by comparison. The youngest, Helena, everyone agreed, was the sweetest-tempered.

hallaca

, a mixture of pork, beef, capers, raisins, and olives packed into a cornmeal mush, wrapped in plantain leaves. They had two more children, Jacobo and Helena, fussed over by nannies and governesses, as was the norm. Leonor grew into a striking teenager; an accomplished pianist, she was Virginia and Heriberto’s favorite. Julio apparently vied for his parents’ attention; although he had a happy childhood, this may have been an early spur to his ambition. Jacobo was the mischievous younger son. Although he is scowling in the photograph, his humor and charm could make his elder brother look sullen by comparison. The youngest, Helena, everyone agreed, was the sweetest-tempered.

Helena, Leonor, Julio, and Jacobo. Havana, c. 1910.

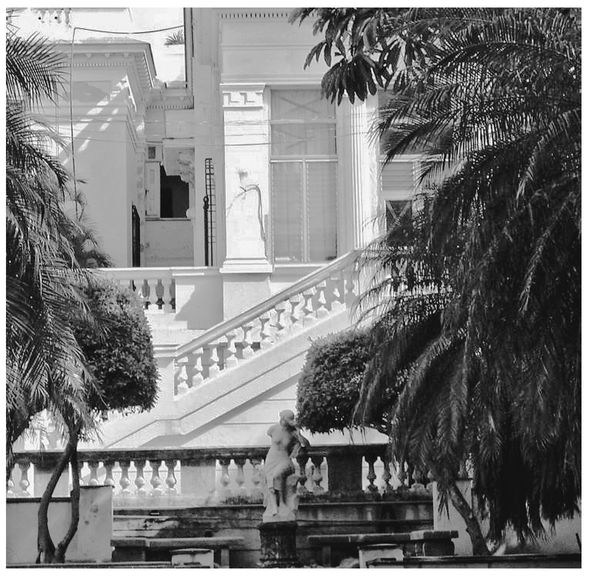

Heriberto later built further homes next door as his children established their own families, so turning the house into a homestead. As adults, Helena lived across the street; Julio in the middle building on Eleventh and Fourth streets next to his parents’ house on the corner; Jacobo on the far corner on the other side, with a garden interconnecting them all around the back. After so many centuries of wandering the world, this family compound in Vedado perhaps seemed to Heriberto like a place which the Lobo family would never need to leave again. To the south, inland up the hill, lay the university. To the north glittered the sea, beyond the domed mosaic tower of St. George’s School. And around them sprang up embassies and other large residences, the highest fronds of the trees planted in their central courtyards reaching above the rooftops, rustling in the sea breeze and giving Vedado a sense of permanence and peaceful lushness. But then Fidel Castro came down from the Cuban Sierra, just like Cipriano Castro had come down from the Venezuelan Andes many years before, and the appropriated Lobo house became an annex to the Culture Ministry, watched over by a stern guard with dark glasses behind a barred gate. “The Castros have always had it in for the Lobos,” Lobo liked to quip as an old man.

A SHORT WORD about Cuba’s old homes, if only to preempt arguments that will surely arise later. They are a touchstone of exile experience. No other place gives such a sense of belonging. The fact that former owners may not have lived there for almost fifty years does not change that. The old home may have been altered and subdivided by postrevolution residents so that it is unrecognizable. It may now exist only in a yellowing photo album. Yet every detail captured by a camera half a century ago is burnished with memory and association, providing a still point from which life’s unsteadiness in exile can be measured and met. “I will never forget the view from my window,” Lobo’s younger daughter María Luisa wrote in a poignant evocation of the house on Eleventh and Fourth streets, where she grew up. “I yearn for my childhood and that distant world, lost forever.” These old houses also provide a fantasy of escape, nostalgia.

Lobo’s old home, glimpsed through the trees. Havana, 2002.

Few issues are more contentious on either side of the Florida straits. The Havana government often invokes the specter of exiles returning one day and turning people out of their houses. For some older émigrés, the nostalgic dream may still include a hope of reclaiming the house and the wealth it once represented. Yet for most, this nostalgia is less a wish for return than a dream of flight, the old house in Cuba becoming a lottery ticket out of the despair of old age. Younger exile generations have meanwhile raised children and perhaps grandchildren abroad, and so created new memories and new nostalgias. One Miami lawyer in his mid-fifties told me a typical story. He had traveled to Havana and, after much searching, found his father’s old house in the city center. It was half fallen down, the walls and window frames eaten away by the damp and sea air. The door, he said, was open but as uninviting as a wolf ’s mouth, and inside there was the sense of a muffled multitude moving about. Although he well knew that some governments in former Soviet bloc countries had restituted confiscated properties, the last thing he wanted, he said, was to try to reclaim the house one day and become the landlord of a slum property, where several families lived in permanent danger of the roof collapsing on their heads. Sometimes there is no going back because there is nothing to go back to. Then the idea of return has to take on broader meanings. Often, it is less a thirst for revenge than a desire to recreate a new home in the old country.

My mother discovered this when she first revisited the island in 1994. Like the Lobos, her family lived in a group of white stucco houses gathered around a Vedado town block. Her parents occupied one corner of the compound in a house built by their father, Don Pedro, Bernabé’s third son, who gave it to them as a wedding present. Her parents had grown up together in Senado, presided over by Bernabé the great patriarch,

recto como una palma

, as upright as a palm, as the saying went. They were also first cousins, so their marriage prompted endless family mirth about how it could only produce children with pig’s tails. Pedro built more houses around them for his other children, much as Heriberto had done, and they all opened at the back to a central patio, where my great-grandfather, a thin white-haired man whose uniform was a white guayabera and white linen trousers, reigned from a park bench.

recto como una palma

, as upright as a palm, as the saying went. They were also first cousins, so their marriage prompted endless family mirth about how it could only produce children with pig’s tails. Pedro built more houses around them for his other children, much as Heriberto had done, and they all opened at the back to a central patio, where my great-grandfather, a thin white-haired man whose uniform was a white guayabera and white linen trousers, reigned from a park bench.

Standing outside on the pavement again for the first time in thirty-four years, my mother saw the old neoclassical mansion on Nineteenth and Second streets, still shutterless, shaded by flower trees and adorned with columns and metal grillwork. She noticed the rubber trees that she had climbed as a young girl, collecting white resin and rubbing the sticky globules together in her hands to make bouncy balls. She saw the elegant terrace that circled the back of the house, and remembered the green lizard that one day fell from its eaves and tangled itself in her hair. Suddenly she recalled her old telephone number—F2032. The house is now part of the North Korean diplomatic compound, but the door was open. Propelled by old habits, my mother walked in.

Of course not all the grand old families left Vedado after the revolution. Some stayed, out of belief in the revolution’s ideals, others because they could not bear to leave. That was the case with one of my great-uncles, who died soon after the rest of the family had left. Government officials promptly sealed off the house, having been alerted that bourgeois treasure was hidden inside. They eventually found the hoard—silver plates, utensils, parasols, a wedding dress—in closets sealed with concrete, and the story played in local newspapers for a while.

Other Cuban grandees who stayed on in their Vedado homes passed the years living like ghosts among their old possessions. One of the most dramatic of these figures was the Cuban poet Dulce María Loynaz. She lived five blocks north of Don Pedro’s house, six blocks east of Heriberto’s, and was the youngest daughter of the impulsive and brave General Loynaz whom Bernabé had betrayed to the Spanish.

Dulce María was born in 1902, four years after Julio Lobo. A friend of Federico García Lorca and the Chilean Nobel Prize winner Gabriela Mistral, she wrote and published poetry through her youth and middle years, and then stopped suddenly in 1960. She lived for the next thirty-eight years in virtual seclusion in her Vedado home, like a tropical Miss Havisham, with her two sisters and one brother, some servants, and an exquisite collection of paintings, sculpture, and delicate china. The authorities thought Dulce María’s spare and classically inspired poems too effete or otherworldly to be published in a country where issues were painted in black and white, for or against, and were described with sledgehammer words like Sacrifice, Solidarity, and Revolution. But mostly they treated her neither badly nor well; they simply left her alone. “Yo Soñaba en Clasificar,” “I Dreamed of Classifying,” is one of her most popular poems:

I had a dream of classifying

Good and Evil, the same way scientists

classify butterflies:

Good and Evil, the same way scientists

classify butterflies:

I dreamed that I pinned Good and Evil

on to the dark velvet background

of a glass display case . . .

on to the dark velvet background

of a glass display case . . .

Below the white butterfly

a label that read “Good”.

Under the black butterfly,

a label that said “Evil”.

a label that read “Good”.

Under the black butterfly,

a label that said “Evil”.

But the white butterfly

was not so Good, nor the black butterfly

so Evil . . . And between my two butterflies,

all the world’s green, golden and infinite butterflies flew.

was not so Good, nor the black butterfly

so Evil . . . And between my two butterflies,

all the world’s green, golden and infinite butterflies flew.

Dulce María had to wait until 1991 for her first book of poems to be published in Cuba. The following year, she unexpectedly won Spain’s prestigious Cervantes literary prize. Dulce María was eighty-nine years old when she traveled to Madrid, and so frail that she had to take the Spanish queen’s congratulatory call from a sickbed, surrounded by flowers that she was too sick to smell, and chocolates that the doctor said she was too old to eat. Shortly before her death five years later, an interviewer asked this most aristocratic of writers why she had never left the island after the revolution. Dulce María simply replied: “I was here first.”

For some reason, my mother carried a Dictaphone when she walked into the North Korean diplomatic compound. On the recording you can hear the click of doors, her gasps of surprise and disappointment as she looked into the rooms of her old home, her voice echoing in the empty corridors. She saw the same black-and-white tiles in the hallway that she remembered, the same glass sliding door to the drawing room, and the same curved marble staircase that she walked down in her wedding dress on her father’s arm after the revolution had begun. She also remembered the side table, on which sat a bronze Medusa’s head with serpents entwined in its hair; the two black wicker chairs that flanked it, where her aunts would place her

en penitencia

, for punishment, whenever she lied or stole; and the piano, where her mother played pieces by the Cuban composer Ernesto Lecuona or the latest popular American hits, like “Saturday Night Is the Loneliest Night of the Week” and “Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate the Positive.” The table, the Medusa, the telephone, the piano, and the black chairs were all gone, of course.

en penitencia

, for punishment, whenever she lied or stole; and the piano, where her mother played pieces by the Cuban composer Ernesto Lecuona or the latest popular American hits, like “Saturday Night Is the Loneliest Night of the Week” and “Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate the Positive.” The table, the Medusa, the telephone, the piano, and the black chairs were all gone, of course.

Suddenly there is a gabble of foreign voices in the background and the sound of footsteps on stairs. “The North Koreans are coming,” my mother whispers into the tape recorder, and then giggles like a naughty schoolgirl caught in a prank. The North Korean voices grow louder, my mother makes a polite protest, everyone switches to Spanish, and there is a rustle as she jams the Dictaphone to the bottom of her shoulder bag. Then there is a click, and the recording goes dead.

Four

SUGAR RUSH

While the ancient countries of Europe are consumed by war, in little Cuba there reigns a carnival of madness and laughter.

Other books

Missing Linc by Kori Roberts

Driven by Emotions by Elise Allen

Jeanne Glidewell - Lexie Starr 04 - With This Ring by Jeanne Glidewell

The Shadows of God by Keyes, J. Gregory

Wake Unto Me by Lisa Cach

Spare and Found Parts by Sarah Maria Griffin

In the Dead of Night by Aiden James

Undercover by Beth Kephart

The Big Killing by Annette Meyers

From the Indie Side by Indie Side Publishing