The Sugar King of Havana (9 page)

Read The Sugar King of Havana Online

Authors: John Paul Rathbone

In Havana, the first car arrived, then the first tramway, and the Mutual Incandescent Company turned on the city’s first electric streetlamps. Drains were dug and modern bathrooms installed in old Spanish homes. Public buildings were repaired, streets paved, dock facilities improved, and new telephone lines installed. The scruffy bathing huts and fishermen’s houses that lined the city seafront were razed, the ground leveled, and the beginnings of a seafront corniche, the famous Malecón, built in a broad sweep across the bay. Three-story houses rose in new suburbs to the west, and a capitol building was commissioned for a site outside the old city walls that had been used as a garbage dump in colonial times. Looking much like the White House in Washington, D.C., but thirteen feet taller, it cost $20 million to build—enriching at least one generation of politician-contractors—and squatted athwart the Prado, top-heavy with bronze and Italian marble.

It is hard now to imagine the wealth that sugar once created—especially as it has become such a mundane commodity. After the war, there may not have been the same fortunes to be made in Cuba as during the colonial years when the Condesa de Merlin said Havana life recalled

les charmes de l’âge d’or

. Still, there was great excitement in the United States about the island’s prospects. Cuba was variously depicted as “virgin land,” a “new California,” “a veritable Klondike of wealth.” The destruction of the war also created stupendous business opportunities, and American carpetbaggers, speculators, and investors descended on the island.

les charmes de l’âge d’or

. Still, there was great excitement in the United States about the island’s prospects. Cuba was variously depicted as “virgin land,” a “new California,” “a veritable Klondike of wealth.” The destruction of the war also created stupendous business opportunities, and American carpetbaggers, speculators, and investors descended on the island.

Old Cuban businesses struggled during what became known as the “second occupation.” Racked by malaria, Bernabé contemplated selling Senado to one of the foreign syndicates buying land around Camagüey for “$2 or $4 an acre, depending on the want of the owner.” The weather still seemed bent on ruining his enterprise: after the rain came drought and fires that crackled through the cane. Mortgaged, sick, and without enough money to attend his eldest son’s wedding in Havana, Bernabé wrote in a moment of despair: “The life of an

hacendado

is hell.”

hacendado

is hell.”

Yet Bernabé did dig his mill out of the mud and eventually prosper. For this, the “enemy of the revolution” was lauded as a patriot. It was a sign of how fast Cuba had changed. The new Republic had many deficiencies. The first president, General Tomás Estrada Palma, was honest but ineffective, drawn from the rebel ranks like the Cuban presidents that followed him, and all better warriors than governors in times of peace. Worst of all was the new constitution’s hated Platt Amendment, by which Washington arrogated the right to intervene after U.S. troops left in May 1902—they would twice return. Even so, Cubans, bored with their colonial past, turned to the future with excitement, and the first decades of the century were optimistic years, the time of the

self-made man

as he was referred to in English; adroit, hardworking, and socially mobile. The island glittered with promise. After independence, some 100,000 exiles returned to the island with small amounts of capital or credit and valuable work experience gained in the United States. Despite the ferocity of the war, half a million Spaniards also came to try to make their fortune. Then there were men like Heriberto Lobo, Julio Lobo’s father, the epitome of the

self-made man,

who had recently lost one fortune in Venezuela and arrived in the new Cuban Republic at the start of the century, like so many others, to start again.

self-made man

as he was referred to in English; adroit, hardworking, and socially mobile. The island glittered with promise. After independence, some 100,000 exiles returned to the island with small amounts of capital or credit and valuable work experience gained in the United States. Despite the ferocity of the war, half a million Spaniards also came to try to make their fortune. Then there were men like Heriberto Lobo, Julio Lobo’s father, the epitome of the

self-made man,

who had recently lost one fortune in Venezuela and arrived in the new Cuban Republic at the start of the century, like so many others, to start again.

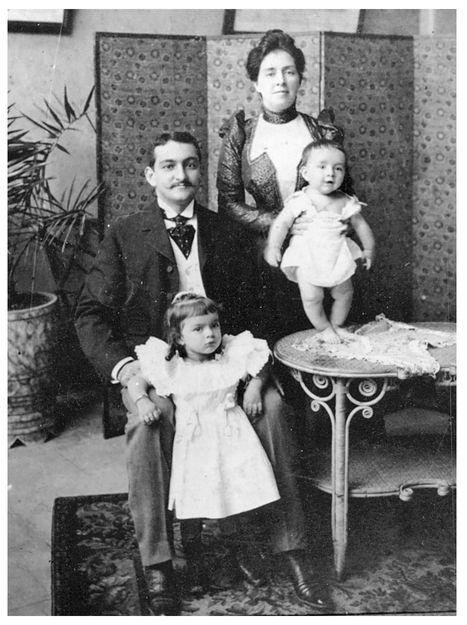

IN FACT IT was a quirk of fate that brought Don Heriberto, his wife, Virginia, and their two young children to Cuba in the autumn of 1900. A tall and moderately good-looking man with a broad forehead, aquiline nose, and deep dark eyes, Heriberto was born in 1870 in Puerto Cabello on Venezuela’s Caribbean coast to a long Sephardic line that almost embodied the medieval image of the wandering Jew. Since the Jewish expulsion from Spain in 1492, Heriberto’s ancestors had lived in Portugal, Amsterdam, London, Amsterdam again, then Saint Thomas, Venezuela, and now Cuba. Arriving penniless in Havana, Heriberto had already pulled his life up by the bootstraps once before. Just fourteen when his father died, Heriberto joined the Banco de Venezuela, the national bank, working as a clerk to support his mother and family. Six years later, after learning accounting, French, and English in his spare time, he was appointed chief accountant. By the time he was twenty-two, Heriberto had joined the board of directors. Three years later he ran the bank; it was a remarkable achievement.

Heriberto and Virginia in Caracas, 1899.

Leonor stands at the front, Julio on the table.

Leonor stands at the front, Julio on the table.

Virginia Olavarría, his wife, was six years older. The eldest daughter of an aristocratic Basque family that had settled in Venezuela in the sixteenth century, she had wavy dark hair and was handsome rather than beautiful. They married in Caracas in 1896, after Heriberto converted to Catholicism; their first child, Leonor, was born the following year and Julio the year after. Life seemed to be full of promise for the young couple in Caracas on the eve of the new century, until President Cipriano Castro threw them out of the country.

Castro was an

andino

, a native of the mountainous Venezuelan state of Táchira near the Colombian border. A brave military leader, like his unrelated Cuban namesake, and a vain man, Castro had a shock of dark hair and burning black eyes that many commented on; he was “a cockerel,” as his father described him, “made for fighting and women.” In 1899, he marched on Caracas from the Andes with a thin column of sixty men—“whistling, happy, clean dressed, as if for a party.” Armed, ironically, with rifles called

cubanos

, they took the capital five months later. But the country was bankrupt, the treasury empty, and Castro soon summoned Heriberto to the Presidential Palace and asked him to open the Banco de Venezuela’s vaults. When Heriberto refused, saying that would “ruin the bank,” Castro threw him in jail and thirty days later expelled him and Heriberto’s immediate family from the country. The Lobos sailed to the United States, planning to settle, but an American banker read an interview that Heriberto gave to a newspaper on arrival in New York. Impressed by how Heriberto had stood up to Castro, the “Monkey of the Andes,” he offered Heriberto a job in Havana as deputy manager of the North American Trust Company, which acted as fiscal agent for the U.S. troops on the island. (“The American people,” Heriberto commented wryly, “are easily impressed by anyone they believe is a victim of injustice.”) With no better immediate prospects, Heriberto accepted and arrived with his family in Havana on October 21, 1900, the eve of his thirtieth birthday. Leonor, his eldest daughter, was two years old at the time; Julio, one. “I came to Cuba with the new century,” as Lobo later liked to say.

andino

, a native of the mountainous Venezuelan state of Táchira near the Colombian border. A brave military leader, like his unrelated Cuban namesake, and a vain man, Castro had a shock of dark hair and burning black eyes that many commented on; he was “a cockerel,” as his father described him, “made for fighting and women.” In 1899, he marched on Caracas from the Andes with a thin column of sixty men—“whistling, happy, clean dressed, as if for a party.” Armed, ironically, with rifles called

cubanos

, they took the capital five months later. But the country was bankrupt, the treasury empty, and Castro soon summoned Heriberto to the Presidential Palace and asked him to open the Banco de Venezuela’s vaults. When Heriberto refused, saying that would “ruin the bank,” Castro threw him in jail and thirty days later expelled him and Heriberto’s immediate family from the country. The Lobos sailed to the United States, planning to settle, but an American banker read an interview that Heriberto gave to a newspaper on arrival in New York. Impressed by how Heriberto had stood up to Castro, the “Monkey of the Andes,” he offered Heriberto a job in Havana as deputy manager of the North American Trust Company, which acted as fiscal agent for the U.S. troops on the island. (“The American people,” Heriberto commented wryly, “are easily impressed by anyone they believe is a victim of injustice.”) With no better immediate prospects, Heriberto accepted and arrived with his family in Havana on October 21, 1900, the eve of his thirtieth birthday. Leonor, his eldest daughter, was two years old at the time; Julio, one. “I came to Cuba with the new century,” as Lobo later liked to say.

The Lobos had arranged lodgings in Vedado, now a residential area of stately mansions to the west of the old city, then an almost rural area with cows tethered on vacant lots. Heriberto reported for work at the North American Trust. Shortly thereafter, when the bank’s American manager died of yellow fever, Heriberto was promoted to the top in a macabre leap over his boss’s corpse. This stroke of fortune, along with his Venezuelan experiences, left Heriberto with an enduring sense of equanimity and generosity of spirit; it also made him alert to the possibilities of luck. Vaulted into the commercial world of postcolonial Havana, Heriberto met Luis Suárez Galbán, a gruff and hardworking Canary Islander. Galbán had arrived in Cuba in 1867, aged fifteen, first sleeping on the floor of his uncle’s struggling import business. Several bankruptcies and restructurings later, the diligent Galbán had transformed it into a prosperous merchant house. Heriberto joined in 1904 after the U.S. troops left. He arranged the financing that planters needed to harvest their cane and, after the

zafra,

with his fluent English, French, and Spanish, sold their sugar abroad.

zafra,

with his fluent English, French, and Spanish, sold their sugar abroad.

Galbán’s business survived the onslaught of the American carpetbaggers, his firm “emerging more powerful than ever from the struggle,” as Galbán put it. And it continued to prosper thereafter, with Heriberto deploying his talents as a prudent and humane administrator alongside Galbán. Virgilio Pérez, later a senior manager and close friend, remembered meeting Heriberto on his first day as a nervous young employee. He reported to Heriberto’s office and grew even more alarmed when he heard shouting inside. The door suddenly swung open and a distressed clerk scurried down the hall. Before him stood Heriberto, smiling broadly and entirely at ease.

“Come in, don’t worry,

mi hijo

, my son,” he told Pérez. “Sorry that I made you wait. . . . All those harsh words you heard for that

mozo

—pure fiction. He thought I was furious. But it’s the only way of getting these youngsters to work. You know the saying,

quien bien te quiere, te hará llorar

, who loves you well will make you cry.”

mi hijo

, my son,” he told Pérez. “Sorry that I made you wait. . . . All those harsh words you heard for that

mozo

—pure fiction. He thought I was furious. But it’s the only way of getting these youngsters to work. You know the saying,

quien bien te quiere, te hará llorar

, who loves you well will make you cry.”

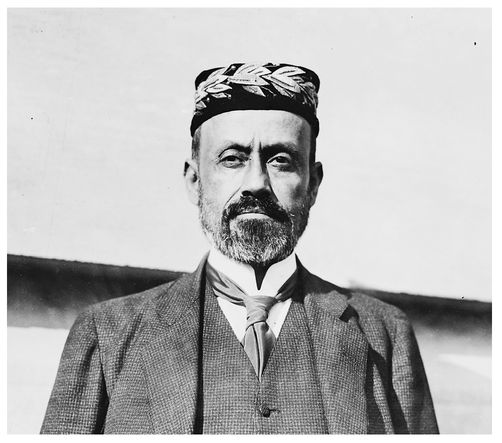

Cipriano Castro in 1913, the year of Virginia’s revenge in Havana.

From Heriberto, Lobo inherited ambition and humor; from his fiery mother, a sharp temper. “May the mountains fall on your head,” Virginia had shouted at Castro’s Presidential Palace as she left Caracas, shaking a fist at the despot who had run her family out of the country. A small Venezuelan earthquake almost did just that ten months afterward, although Virginia exacted a more satisfying revenge thirteen years later. Castro, by then deposed from power, had arrived in Havana to drum up support for a counterrevolution. He sped through customs, clad in white flannels, swinging a silver-topped cane, and his drive through the city turned into a procession as a fifty-strong orchestra playing national Venezuelan and Cuban songs led the way. Virginia, meanwhile, headed to Castro’s hotel, the Inglaterra, and waited in the lobby. When Castro appeared, she rushed him with her parasol, and hotel staff had to pry the umbrella from her hands as she beat her old enemy around the head.

Cuba’s self-made men pursued their interests. The island prospered. Senado now milled some fifteen thousand tons of sugar a year, a crop worth almost $1 million, and Bernabé had become a

personage

, a man who could ride in his own Pullman carriage direct from his mill in Camagüey to Havana’s central railway station. Galbán’s business also expanded; he bought three mills, operated the Westinghouse concession in Cuba, and opened a trading office on Wall Street with equity capital of $1 million. Heriberto remained in Havana as co-head of the Cuban operation.

personage

, a man who could ride in his own Pullman carriage direct from his mill in Camagüey to Havana’s central railway station. Galbán’s business also expanded; he bought three mills, operated the Westinghouse concession in Cuba, and opened a trading office on Wall Street with equity capital of $1 million. Heriberto remained in Havana as co-head of the Cuban operation.

By now the Lobos had put down roots. Heriberto and Virginia bought the Vedado house they had first settled in, paying six thousand pesos to Doña Lucia, a Sicilian who owned the building with her Cuban husband, a failed sugar planter who sported a white mustache with sharp ends that pointed upward like the kaiser’s. Three stories high, the house stood on a breezy rise in Vedado, shaded by ficus trees. Although roomy, its simple white stucco front seemed plain compared with some of the other palaces built around them in Renaissance, Moorish, or belle époque styles. Among the string of markers that locate the Lobo family in Havana’s prerevolutionary social geography, there was the house of Mario García Menocal, a general in the War of Independence and one of Cuba’s first presidents; Jacobo later married Menocal’s cousin, Estela. There were also the homes of the Gelats, leading Cuban bankers; the Condesa de Revilla de Camargo, who lived in an ornate mansion built with Carrara marble by her brother, the sugar baron and amateur racing car driver José Gómez Mena; and the imposing Sarrá family residence next door to the Lobos’, with its gardens and chapel. The Sarrás were well connected, big in pharmaceuticals and real estate, and renowned for their wealth, a source of gentle rivalry with their neighbors. Pérez tells the story of how Heriberto tripped and fell while on a business trip abroad. Surprised by the attention he received from some of the female guests in his hotel when it became known that a “Cuban millionaire” had hurt his leg, Heriberto asked his traveling companion: “Do you see any change in me?” “Not really, you seem the same,” Pérez replied. “Ahh, just as I thought,” Heriberto mused. “I’ve no extra magnetism, or animal charisma, or sex appeal. What these noble women are responding to is my Sarrá-appeal.”

Other books

Biarritz Passion: A French Summer Novel by Laurette Long

A Christmas Promise by Mary Balogh

Stryker by Jordan Silver

Dear Mystery Guy (Magnolia Sisters Book 1) by Brenda Barrett

Most Eagerly Yours by Chase, Allison

Fate Intended (The Coulter Men Series Book 3) by Seckman, Elizabeth

Death Row Apocalypse by Mackey, Darrick

A Ticket to the Boneyard by Lawrence Block

The Lady In Red: An Eighteenth-Century Tale Of Sex, Scandal, And Divorce by Hallie Rubenhold

Native Dancer by John Eisenberg