The Sugar King of Havana (24 page)

Read The Sugar King of Havana Online

Authors: John Paul Rathbone

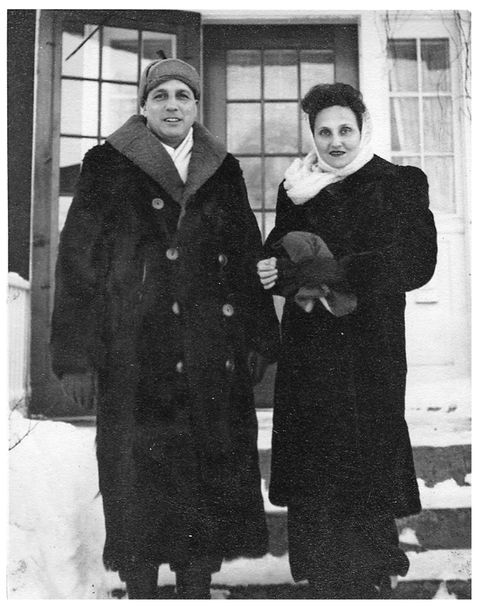

MY OWN FAMILY also removed themselves from the hurly-burly of Cuban life during this period, and also for reasons of health. Around the time that Lobo was shot, my grandfather was stricken with tuberculosis. His doctor recommended a long period of convalescence in a North American sanatorium. My grandmother borrowed money from her father and in the winter of 1944, she, my mother, her brother, her sister, and my grandfather left Cuba for an eighteen-month stay at a nursing home by Lake Placid, New York, a traditional rest cure for tuberculosis sufferers.

My mother’s recollections of that time—everyone wrapped in thick coats, snow on the rooftops, with white hills and bare trees in the background—seem incongruous compared with the more tropical memories of her childhood. My maternal grandfather, a gentle and studious man, said it was the happiest time in his life. Wrapped in blankets, with the snow-covered hills of New York State in view through his bedroom win-dow, he reread his favorite book,

The Magic Mountain

, Thomas Mann’s description of the intellectual development of Hans Castorp, a young German tuberculosis sufferer, in a Swiss sanatorium during the second decade of the twentieth century. At the end of the novel, Castorp discharges himself from the “half-a-lung club” and descends to the “flat-lands” of Europe, where he dies among millions of other anonymous conscripts during World War I. I cannot help but wonder if my grandfather, suffering from tuberculosis like the hero of Mann’s novel, felt any sense of doom when he returned to the flat sugar plains of Cuba.

The Magic Mountain

, Thomas Mann’s description of the intellectual development of Hans Castorp, a young German tuberculosis sufferer, in a Swiss sanatorium during the second decade of the twentieth century. At the end of the novel, Castorp discharges himself from the “half-a-lung club” and descends to the “flat-lands” of Europe, where he dies among millions of other anonymous conscripts during World War I. I cannot help but wonder if my grandfather, suffering from tuberculosis like the hero of Mann’s novel, felt any sense of doom when he returned to the flat sugar plains of Cuba.

My grandparents, Lake Placid, 1948.

My grandfather’s forebears, men such as Colonel Enrique Loret de Mola, had once risked all in Cuba’s political struggles. By contrast, everybody in Havana now wrinkled their noses when anyone mentioned politics, while politicians were viewed as “non-U,” in Nancy Mitford’s phrase, or violent and corrupt—often all three. “They’re all the same” was the common and disheartening refrain heard across the island. Removed from political life, like so many of his peers, my grandfather worked at the store and raised his family. His greatest consolations lay in the music of Beethoven, rare books of Buddhist thought, and the writings of the Catholic philosopher Miguel de Unamuno. I have his copy of

The Tragic Sense of Life

, Unamuno’s meditation on the quixotic human desire for immortality, the longing for everything—homes, families, even countries and ways of life—to remain the same. It is also the same edition that my grandfather read many years later while in exile, when his feelings of impermanence were strongest, and the margins are filled with notes and whole pages of text are underlined.

The Tragic Sense of Life

, Unamuno’s meditation on the quixotic human desire for immortality, the longing for everything—homes, families, even countries and ways of life—to remain the same. It is also the same edition that my grandfather read many years later while in exile, when his feelings of impermanence were strongest, and the margins are filled with notes and whole pages of text are underlined.

Lobo also sought out fresh consolations after his return to Havana. There were his growing Napoleon collection and his love affairs, which became ever more complicated and varied. Lobo’s work remained as important as before, and the biggest deals were yet to come. Yet even these triumphs were now tempered by a sense of evanescence.

The following October, he and María Esperanza divorced. She had long known about his affairs; formal separation was only a matter of time, and it was easier with their two daughters abroad at school. They reached a settlement and sold their place in Miramar. María Esperanza set up a new house, and Lobo moved back to his parents’ in Vedado and sought to regather himself at his childhood home. Instead, he found only more sadness and death. Less than a year later, his mother died. Imperious Virginia, who had seemed almost immortal in her family’s eyes when she had smashed an umbrella over Cipriano Castro’s head, had been unwell for several months, slipping in and out of a coma, no longer recognizing the familiar faces around her bed.

“Fortunately she suffered nothing, and went out like a candle,” Lobo wrote to María Luisa in Pennsylvania. “We were all by her side when she died, and afterwards her face rejuvenated itself. She seemed only thirty years old. You’ve no idea how marked the change was. She became a young woman again.”

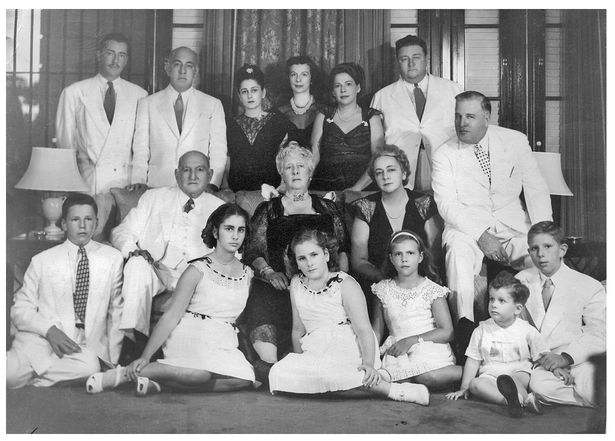

The Lobo family. Heriberto, Virginia, Helena, and her husband, Mario Montoro, are

in the middle. Lobo is second from the left at the back, next to María Esperanza.

Jacobo stands on the far right. Leonor and María Luisa

sit in the middle at the front.

in the middle. Lobo is second from the left at the back, next to María Esperanza.

Jacobo stands on the far right. Leonor and María Luisa

sit in the middle at the front.

Six weeks later, Lobo’s spry eighty-year-old father collapsed, felled literally by a broken heart. Heriberto had been married to Virginia for fifty-five years. Death caught him on a glorious December morning as he dressed for battle at the office, like a good general, with his boots on. Heriberto regained consciousness one last time after he was found on the floor of his bedroom. When placed on his bed, Heriberto addressed his last thoughts and words to the worried faces gathered around him. “

¿Qué pasa?

” he asked—What is the matter? One unfortunate answer came two months later on St. Valentine’s Day, when Lobo’s younger brother, Jacobo, committed suicide with a bullet to his head. Some said it was because of drugs or alcohol; others, love; some that his business affairs had turned sour.

¿Qué pasa?

” he asked—What is the matter? One unfortunate answer came two months later on St. Valentine’s Day, when Lobo’s younger brother, Jacobo, committed suicide with a bullet to his head. Some said it was because of drugs or alcohol; others, love; some that his business affairs had turned sour.

It happened early in the morning, and the single shot woke Lobo, whose bedroom was across the hallway from Jacobo’s. Since his divorce and Jacobo’s recent separation from his own wife, Estela Menocal, the two brothers had lived together as bachelors at their parents’ old house on the corner of Eleventh and Fourth. They were the antithesis of each other and made for odd housemates. While Lobo worked and studied, Jacobo drank and socialized. Jacobo was often rash at work; it was said that his two mills, Amazonas and Limones, were failing. While Lobo kept himself trim, Jacobo’s waistline was a balloon. Yet any jealousy flowed both ways. Jacobo was

simpático,

he had

un don de la gente,

a gift for people. So although it was his elder brother who enjoyed business success, it was Jacobo who held the floor at parties. Living together, they had grown close again, and any former rivalries had dissolved. After Jacobo’s death, Lobo put the squeeze on his brother’s business partners, and when he had finished, Jacobo’s sons had inherited $1 million between them.

simpático,

he had

un don de la gente,

a gift for people. So although it was his elder brother who enjoyed business success, it was Jacobo who held the floor at parties. Living together, they had grown close again, and any former rivalries had dissolved. After Jacobo’s death, Lobo put the squeeze on his brother’s business partners, and when he had finished, Jacobo’s sons had inherited $1 million between them.

Lobo found himself suddenly alone. Sharp physical pain and the recurring operations that he had to endure were frequent reminders of his own near-death experience. “The truth is I have been unlucky lately,” he wrote to María Luisa after an unfortunate fall. “Gun shots, a broken skull, broken ribs, sinusitis, operations on my spine, headaches, stomach cramps, a bust sacroiliac, and now a broken leg. I’ve had my full quota in the past few years, hopefully those that come will be happier and more tranquil.”

Lobo’s condition mirrored that of his country; prosperous and hopeful, but battered. The Prío government was better than Grau’s. Debonair and charming, the “President of Cordiality” surrounded himself with able technocrats, the sugar price was high at over 5 cents a pound, the economy growing, and the press was free.

¡Qué Suerte Tiene El Cubano!

, how lucky Cubans are, ran a popular Bacardi rum advertising slogan that summed up the national mood. But El Presidente Cordial, the man who told Lobo on the night of the shooting that he didn’t know who had tried to kill him, could not or would not end Cuban gangsterism and corruption. While Prío took delight in La Chata, his luxurious farm outside Havana that was fitted out with what has been called the understatement of a Busby Berkeley production, Cubans felt that the corruption of Grau’s years was repeating itself.

¡Qué Suerte Tiene El Cubano!

, how lucky Cubans are, ran a popular Bacardi rum advertising slogan that summed up the national mood. But El Presidente Cordial, the man who told Lobo on the night of the shooting that he didn’t know who had tried to kill him, could not or would not end Cuban gangsterism and corruption. While Prío took delight in La Chata, his luxurious farm outside Havana that was fitted out with what has been called the understatement of a Busby Berkeley production, Cubans felt that the corruption of Grau’s years was repeating itself.

Prío’s presidency came to a premature end, hastened—if only indirectly—by a charismatic rival, Eddy Chibás. An emotional man who always dressed in white, Chibás was also genuinely honorable, the heir to a huge fortune, and totally uninterested in money. Widely seen as the man most likely to win the 1952 election, his favorite image was the broom—to sweep away corruption. His favorite word was

aldabonazo

—the sharp knock or wake-up call. His political prescription was to throw corrupt politicians in jail. And his greatest weapon was the radio. Cuba literally stopped every Sunday at 8 p.m. to listen to Chibás’s increasingly hysterical broadcasts on the CMQ station. His show on August 5, 1951, ended in a typically ringing style, with a description of Cubans as a Chosen People, defeated by original sin.

aldabonazo

—the sharp knock or wake-up call. His political prescription was to throw corrupt politicians in jail. And his greatest weapon was the radio. Cuba literally stopped every Sunday at 8 p.m. to listen to Chibás’s increasingly hysterical broadcasts on the CMQ station. His show on August 5, 1951, ended in a typically ringing style, with a description of Cubans as a Chosen People, defeated by original sin.

“Geographical position, rich soils and the intelligence of its inhabitants mean that Cuba is destined to play a magnificent role in history, but it must work to achieve it,” Chibás harangued. “The historical destiny of Cuba, on the other hand, has been frustrated until now by the corruption and blindness of its rulers. . . . People of Cuba, arise and walk!” he screamed. “People of Cuba, awake! This is my last call!” Then Chibás shot himself in the stomach. Rushed to the hospital, he died of internal bleeding eleven days later.

Probably an accident more than a suicide, the probable reason for Chibás’s self-immolation was his inability to provide proof of corruption charges he had made against one of Prío’s ministers. Chibás was also Cuba’s great hope, and his death created a political vacuum. Into it stepped Batista. The former president, still popular with the military and rural vote, had returned from Florida hoping to make a comeback in the forthcoming election. But his campaign sputtered, and a December poll showed him trailing in third place. Faced with the prospect of losing the vote, and encouraged by disaffected army officers who believed that Prío was planning a coup—although there was no evidence of this—Batista literally took the country by surprise.

At around 3 a.m. on March 10, 1952, Batista drove up to the main gate of the Camp Columbia army base in a Buick with his co-conspirators. He was waved through by the captain of the guard, who was a party to the plot. Once inside, they arrested the chiefs of staff. Tanks were dispatched to the Presidential Palace; Prío drove off to seek support from loyal regiments outside Havana, but found that they had changed sides. The whole affair took only a few hours. Cubans woke that morning to martial music on the radio and found out that Prío was no longer president, that Batista was again their ruler, and there would be no election in June—although one was promised soon. The former stenographer declared: “The people and I are dictators.”

Prío went into exile with his family after taking refuge in the Mexican embassy. “They say that I was a terrible President of Cuba,” he remarked later. “That may be true. But I was the best President Cuba ever had.” Fifteen years later in Miami, Prío shot himself, as Chibás had done. Nobody had noticed that he was feeling depressed; Prío was cordial until the last.

Like Cuba itself, Lobo was left without a compass. He had no parents to turn to and no wife. His brother had shot himself, and his elder sister Leonor had died many years before. His only other remaining close relative was Helena, his younger sister. His daughters were away at school and he wrote frequent and tender letters to both in his cramped hand, often late at night. He reassured them, made plans for their holidays (trips to a music festival in Europe, fishing jaunts around his mills in Oriente), and visited them whenever he traveled to New York for work. He was philosophical but missed their company dreadfully. “My life alone is no pleasure,” he admitted to María Luisa in one letter.

In Havana, Lobo returned home after work and rattled around the three adjacent houses at Eleventh and Fourth streets. He had lived in one, Jacobo in the second, his parents in the third. Now, except for his own rooms, they were empty. In the evening he sometimes sat with a glass of scotch by the swimming pool in the garden, under the shade of a mango tree. Lobo said he did some of his best thinking there. If Leonor or María Luisa were in town during the holidays, they joined him for a drink. Lobo punctuated the conversation with poetry. Shelley’s “Ozymandias” was one of his favorites.

“. . . Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Within a decade, Lobo’s mighty works would also disappear. Fifty years after that, Castro’s socialist revolution would seem like an Ozymandian dream too.

Other books

The Buenos Aires Quintet by Manuel Vazquez Montalban

The Boy Who Could See Demons by Carolyn Jess-Cooke

Chase (Prairie Grooms, Book Four) by Kit Morgan

Pride of the King, The by Hughes, Amanda

To Catch a Leaf by Kate Collins

The Runaway by Grace Thompson

The Mammoth Book of Unsolved Crimes by Wilkes, Roger

The Fragrance of Geraniums (A Time of Grace Book 1) by Ruggieri, Alicia G.

Shooting for the Stars by R. G. Belsky