The Tao of Natural Breathing (4 page)

Read The Tao of Natural Breathing Online

Authors: Dennis Lewis

THE INNER BREATH

Whatever outer form our breath takes, an inner process of breathing also occurs. This process takes place in the cells, which inhale oxygen from the steady stream of hemoglobin flowing throughout the body and exhale carbon dioxide back into this stream. It is in the cells, and more particularly the mitochondria, where the inhaled oxygen helps transform food into biological energy. This transformation occurs when oxygen is combined with carbon (from food) in a slow-burning fire. The energy released from the interaction of oxygen and carbon is transferred to energy storage molecules, called ATP (adenosine triphosphate), which make it available to all the cells of the body. Waste products, such as carbon dioxide, are returned to the venous blood and ultimately to the lungs and back into the atmosphere.

THE RESPIRATORY CENTER

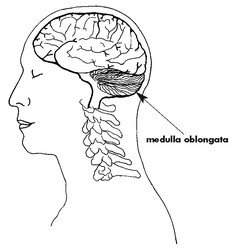

The process of breathing and its relationship to the production of energy in our organism is so fundamental to our survival that nature has given us little direct control over it. Our breathing is thus mostly involuntary, generally controlled by the respiratory center of the autonomic nervous system—especially the vagus nucleus in the medulla oblongata, the nervous tissue at the floor of the fourth ventricle of the brain (

Figure 5

). The respiratory center, which is located near the occiput (where the spine meets the skull), transmits impulses to nerves in the spinal cord that cause the diaphragm and intercostal muscles to begin the process of inhalation. Branches of the vagus nerve coming from this center sense the stretching of the lungs during inhalation and then automatically inhibit inhalation so that exhalation can take place. The respiratory system is connected to most of the body’s sensory nerves; hence any sudden or chronic stimulation coming through any of the senses can have an immediate impact on the force or speed of our breath, or can stop it altogether. Intense beauty, for example, can momentarily “take our breath away,” while pain, tension, or stress generally speeds up our breathing and reduces its depth. We can, of course—within limits—intentionally hold our breath, lengthen or reduce our inhalation and exhalation, breathe more deeply, and so on. When we do so, the nerve impulses generated in the cerebral cortex as a result of our intention bypass the respiratory center and travel down the same path used for voluntary muscle control.

Acid/Alkaline Balance

The respiratory center does its work based on the acid/ alkaline balance of the blood. The cells in the nucleus of the medulla are sensitive to this balance. From the standpoint of our health, the blood must remain slightly alkaline (pH 7.4). Even tiny deviations from this condition can be dangerous. When the body’s chemical activity increases because of physical effort, emotional stress, sensory stimulation, and so on, more carbon dioxide and other acids are produced. This increases the acidity of the blood. To counteract this increase and maintain homeostasis, the respiratory center automatically increases the breath rate. This helps to bring in needed oxygen and to expel excess carbon dioxide. When the body’s chemical activity decreases through relaxation or rest, less carbon dioxide is produced and our breathing automatically slows down.

8

Though we cannot, for the most part, alter the basic chemistry of the respiratory process, we can influence it in a variety of “indirect” ways. One such way is through the relaxation of excessive tension in our postures, movements, and actions. Tension, which involves muscular contraction, produces both lactic acid and carbon dioxide. By reducing chronic tension, we reduce the quantity of these waste products, as well as the work that the body needs to do to counteract them. The relaxation of chronic tension also makes possible the more efficient coordination of the various mechanisms involved in breathing. It is through the harmonious coordination of these mechanisms that we can take in oxygen and expel carbon dioxide with the least possible expenditure of the body’s resources.

THE RESPIRATORY MUSCLES

Healthy breathing involves the harmonious interplay not just of the rib muscles, abdominal muscles, and diaphragm, but also of various other muscles throughout the body. These include the extensor muscles of the back, which keep us vertical in relation to gravity, and the psoas muscles, which connect the vertebrae in the lower thoracic and lumbar areas to the pelvis and thigh bones, and are involved in both hip and spinal flexion (

Figure 6

). Unnecessary tension in the muscles of our shoulders, chest, belly, back, or pelvis—whether it is caused by negative emotions, physical or psychological stress, trauma, injury, or faulty posture—increases the level of carbon dioxide in our blood and interferes with respiratory coordination. It also overstimulates our sensory nerves, which, as we will see later, has an unhealthy influence on our overall functioning.

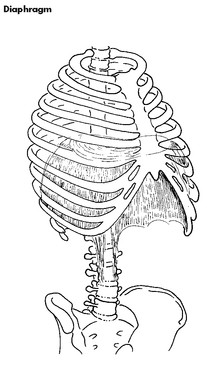

The Diaphragm—the “Spiritual Muscle”

Of all the respiratory muscles, the most important from the standpoint of our overall health is the diaphragm. Though few of us make efficient use of this muscle, it nevertheless lies at the foundation of healthy breathing. Shaped like a large dome, the diaphragm functions as both the floor of the chest cavity and the ceiling of the abdominal cavity (

Figure 7

). It is penetrated by—and can affect—several important structures, including the esophagus, which carries food to the stomach; the aorta, which carries blood from the heart to the arteries of all the limbs and organs except the lungs; the vena cava, the central vein that carries venous blood from the various parts of the body back to the heart; and various nerves including the vagus nerve, which descends from the medulla oblongata and branches to the various internal organs.

Although breathing can continue even if the diaphragm stops functioning, it is the rhythmical contraction and relaxation of the diaphragm that animates our breath and plays an important role in promoting physical and psychological health. When we inhale, the diaphragm normally contracts. This pulls the top of its dome downward toward the abdominal organs, while the various chest muscles expand the rib cage slightly outward and upward. This pumplike motion creates a partial vacuum, which, as we know, draws air into the lungs. When we inhale fully, the diaphragm can double or even triple its range of movement and actually massage—directly in some cases, indirectly in others—the stomach, liver, pancreas, intestines, and kidneys, promoting intestinal movement, blood and lymph flow, and the absorption of nutrients.

Even a slight increase in the diaphragm’s movement downward not only has a beneficial impact on our internal organs, but also brings about a large increase in the air volume of the lungs. For every additional millimeter the diaphragm expands, the volume of air in our lungs increases by some 250 to 300 milliliters. Research done in mainland China demonstrates that novices working with deep breathing can learn to increase the downward movement of their diaphragms by an average of four millimeters in six to 12 months. They are thus able to increase the volume of air in their lungs by more than 1,000 milliliters—in a year or less.

9

At maximum inhalation, the muscles of the abdomen naturally contract to counterbalance the movement of the diaphragm downward and help limit the further expansion of the lungs. As exhalation begins, the diaphragm relaxes upward, its elasticity helping to expel used air from the lungs. When we exhale completely, the diaphragm projects firmly up against the heart and lungs, giving these organs life and support. For Taoist master Mantak Chia, the diaphragm is nothing less than

a spiritual muscle

. “Lifting the heart and fanning the fires of digestion and metabolism, the diaphragm muscle plays a largely unheralded role in maintaining our health, vitality, and well-being.”

10

Restrictive Influences on the Diaphragm

Unfortunately, most of us do not experience the full benefit of this “spiritual muscle.” There are two major reasons for this. First, the movement of the diaphragm is adversely influenced by the sympathetic nervous system as a result of the chronic stress, fear, and negativity in our lives (I will discuss the sympathetic nervous system in more detail in the next chapter). Second, it is also adversely influenced by unnecessary tension in our muscles, tendons, and ligaments, as well as by the faulty configurations of our skeletal structure. In understanding this second point, it is useful to know something about how and where the diaphragm actually attaches to the skeletal structure. Though most of the body’s muscles are attached to two different bones—one fixed, called the “origin,” and one which moves as a result of muscle contraction, called the “insert”—the diaphragm is not attached in this way. The diaphragm is fixed to the inside of the lower ribs as well as to the lumbar spine, close to the psoas muscles, but it does not “insert” to any bone. Rather, it inserts to its own central tendon, which lies just under the heart (

Figure 8

). The diaphragm is thus influenced by the health and mobility of the spine and pelvis, and their associated muscles, and these in turn are influenced not just by our habitual postures, but also by our emotions and attitudes.

One of the most adverse influences on the movement of the diaphragm is the unnecessary tension that many of us carry in our abdominal muscles and internal organs. Most of these tensions are the result of chronic stress, repressed emotions, and excessive negativity, but they also can be caused by the prevailing image of the hard, flat belly that we find in fashion magazines and fitness centers. When the belly is overly contracted it resists the downward movement of the diaphragm. When this occurs, the diaphragm’s central tendon replaces the rib cage and spine as the diaphragm’s fixed point, and the contraction of the diaphragm during inhalation causes excessive elevation of the ribs.