The Tao of Natural Breathing (5 page)

Read The Tao of Natural Breathing Online

Authors: Dennis Lewis

Compensating for a Poorly Functioning Diaphragm

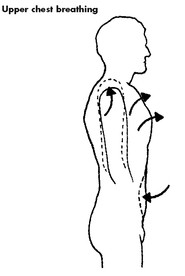

To attempt to compensate for decreased lung space resulting from a contracted belly and a poorly functioning diaphragm—especially in times of physical or psychological stress (when more energy is needed)—we either have to breathe faster (which may result in hyperventilation and the emergence of the “fight or flight reflex”) or we have to increase the expansion of the thoracic cage and raise the clavicles. Because the thoracic cage and clavicles are relatively rigid, however, this further expansion requires the expenditure of extra muscular effort and energy, and ultimately results in less oxygen being taken in during each breath. If someone were to ask us to take a deep breath, most of us would make a big effort to suck in our belly, expand our upper chest, and raise our shoulders—a not-so-funny caricature of “chest breathing”—the way most of us breathe most of the time (

Figure 9

). Such an effort, however, results in a shallow breath, not a deep one. As we shall see more clearly in later chapters, a deep inhalation requires the expansion of the abdomen outward, which helps the diaphragm move further downward and allows the bottom of the lungs to expand more completely. Though it is true that raising the shoulders reduces the weight on the ribs beneath and allows the lungs to expand further at the top, the potential volume at the top of the lungs is much smaller than the potential volume at the bottom. Expanding the top of the chest and raising the shoulders may be an effective emergency measure to take in more air for those of us with little elasticity in our diaphragm, rib cage, and belly, or who have asthma or emphysema, but for most of us it only further entrenches our bad breathing habits and undermines our health and vitality.

THE HARMFUL EFFECTS OF BAD BREATHING HABITS

Breathing based on such habits—habits in which the diaphragm is unable to extend through its full range and activate and support the rhythmical movement of the abdominal muscles, organs, and tissues—has many harmful effects on the organism. It reduces the efficiency of our lungs and thus the amount of oxygen available to our cells. It necessitates that we take from two to four times as many breaths as we would with natural, abdominal breathing, and thus increases energy expenditure through higher breath and heart rates. It retards venous blood flow, which carries metabolic wastes from the cells to the kidneys and lungs where they can be excreted before they do harm to the organism. (In this regard, it is important to realize that 70 percent of the body’s waste products are eliminated through the lungs, while the rest are eliminated through the urine, feces, and skin.) It retards the functioning of the lymphatic system, whose job it is to trap and destroy viral and bacterial invaders, and thus gives these invaders more time to cause disease. It also reduces the amount of digestive juices, including the enzyme pepsin, available for the digestive process, and slows down the process of peristalsis in the small and large intestines. This causes toxins to pile up and fester throughout the digestive tract. In short, such breathing weakens and disharmonizes the functioning of almost every major system in the body and makes us more susceptible to chronic and acute illnesses and “dis-eases” of all kinds: infections, constipation, respiratory illnesses, digestive problems, ulcers, depression, sexual disorders, sleep disorders, fatigue, headaches, poor blood circulation, premature aging, and so on. Many researchers even believe that our bad breathing habits also contribute to life-threatening diseases such as cancer and heart disease.

Through the gentle, natural practices in this book, however, we can begin to discover the power of natural breathing to counteract these habits and support the overall health, vitality, and well-being that is our birthright.

PRACTICE

The first step to working with your breath is to be clear in your mind about the actual mechanics, the physiological “laws,” of natural breathing. This mental clarity will help you experience the breathing process both more directly and more accurately. The next step is to deepen your awareness of your own particular breathing patterns. For your first exercise, read this chapter again; as you read, visualize and sense in yourself the various mechanisms being discussed. Don’t try to change anything; just see what you can learn about your own particular breathing process. In the next chapter you’ll have an opportunity to go more deeply into the process of self-sensing and its relationship to your breath and health.

2

BREATH, EMOTIONS, AND THE ART OF SELF-SENSING

... the work with breathing starts

with sensing the inner atmosphere

of our organism—

the basic emotional stance we take

toward ourselves and the world.

The integration of natural breathing into our lives begins with learning how to sense ourselves more completely and accurately—to consciously occupy our bodies. It is through conscious embodiment, the whole sensation of ourselves, that we can awaken to higher levels of organic intelligence, to the “wisdom” of the body. Though we all have the potential to sense our bodies in their entirety, the sensory image we have of ourselves is generally fragmentary and filled with distortions. What’s more, the body we think we know so well is in large part a “historical” body—a body shaped by the past, by the results of our long-forgotten physical and emotional responses to the conditions of our early lives. It is also, of course, shaped by the present, especially by our lack of sensory awareness.

THE WORK OF SENSORY AWARENESS

The term “sensory awareness” first became popular in America in the late 1960s, mainly through the work of Charlotte Selver (who had been giving workshops in America since 1938) and Charles Brooks, two of the pioneers in the human potential movement.

11

Their work was concerned in large part with the effort to discover through sensation what is natural in our functioning, and what is conditioned; what opens us to the reality of the present moment, and what closes us. It is, of course, questions such as these—and the answers that we can we experience in our own individual lives—that are crucial to our health, well-being, and inner growth. Enriched by the psychophysical experiments of Esalen Institute, in Big Sur, California, and the entry of various Asian spiritual traditions into America in the 1960s and 1970s—especially traditions such as Zen Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, and Taoism—the work of sensory awareness demonstrated a new, more fundamental way of relating to ourselves and our energies.

Though the work of sensory awareness begins with our inner and outer senses, it reaches far beyond them into the very meaning of consciousness. Anyone who seriously undertakes this work will quickly discover two remarkable facts. First, that we generally live our lives in a state of “somatic amnesia”—a state in which we are mostly oblivious to the rich, informative sensation of our bodies. What awareness we do have of our bodies is not only filled with enormous gaps, but is often just plain wrong, as physical therapists, body workers, and others are quick to point out. Second, that this somatic amnesia is closely related to our “emotional amnesia,” our frequent inability to feel the emotions and attitudes that are actually motivating our behavior. The gaps in the overall sensation of our bodies are not merely gaps in our bodily awareness; they also represent gaps in our mental and emotional awareness.

As a result of our lack of “integral awareness,” awareness that encompasses our entire being, we have lost touch not only with the gracefulness in action that is our birthright, but, even more importantly, with the extraordinary capabilities of the human organism to sense itself from the inside and to learn new and better ways of functioning through this sensation. Even many of us involved in physical fitness and martial arts have little conscious contact with our bodies, approaching them not through ever-deepening organic awareness but rather through memory, willfulness, coercion, and repetition. The slogan “no pain, no gain” is an extreme example of this approach.

THE WORLD IN THE BODY

From the perspective of Taoism, as well as of Chinese medicine, this lack of integral awareness is harmful to our health. It also deprives us of the vision, the perspective, we need for psychological or spiritual evolution. For the Taoist, the statement “as above, so below” is one of the fundamental truths of life. The body (including the brain) is a microcosm of the universe, and operates under the same laws. Not only is the body “in the world,” but the world is “in the body”—especially the

conscious body

. For those who can be sensitive, who can learn how to sense themselves impartially, the rich landscape of the outer world—the rivers, lakes, oceans, tides, fields, mountains, deserts, caves, forests, and so on—has direct counterparts in the inner world of the body. The energetic and material qualities of the outer world—represented in Taoism by “the five elements”: fire, earth, metal, water, and wood—manifest in the body as the network of primary organs: the heart, spleen, lungs, kidneys, and liver. And the atmospheric movements of matter and energy that we call “weather”—wind, rain, storm, warmth, cold, dampness, dryness, and so on—have their obvious counterparts in the inner atmosphere of our emotions. Likewise, the cosmic metabolism of the outer world—the conservation, transformation, and use of the energies of the earth, atmosphere, sun, moon, and stars—has its counterpart in the metabolism of our inner world, in the movement and transformation of food, air, and energy. To begin to sense the interrelationships and rhythms of the various functions of one’s own body—of one’s skin, muscles, bones, organs, tissues, nerves, fluids, hormones, emotions, and thoughts—is to experience the energies and laws of life itself. As Lao Tzu says: “Without leaving his house, he knows the whole world. Without looking out of his window, he sees the ways of heaven.”

Whether or not we agree with this vision of our organism as a microcosm of the universe, the work of self-sensing will quickly show us that the rhythms of breathing—of inhalation and exhalation—lie at the heart of our physical, emotional, and spiritual lives. We will see that it is through the sensory experience of these rhythms that we can awaken our inner sensitivity and awareness and begin to open ourselves to our inner healing powers—the creative power of nature itself. But for this to occur, our breathing must change from “normal” to “natural”; it must become free from the unconscious motivations and constraints of our self-image.

PERCEPTUAL REEDUCATION AND WHOLENESS

Our faulty patterns of breathing have developed over many years and are tied in closely with our self-image, with our individual patterns of illusion, avoidance, and forgetfulness. As a result, correcting them is not just a matter of applying the right techniques. Nor is it just a matter of going to a physical therapist or other body work practitioner to learn proper breathing mechanics, as we might go to an auto mechanic to fix a faulty carburetor or muffler. It is, rather, a matter of

perceptual reeducation,

of learning how to experience ourselves in an entirely new way, and from an entirely new perspective.