The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction (3 page)

Read The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction Online

Authors: Rachel P. Maines

Tags: #Medical, #History, #Psychology, #Human Sexuality, #Science, #Social Science, #Women's Studies, #Technology & Engineering, #Electronics, #General

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Like all hardworking historians, I have more intellectual debts than I can remember or repay. Over the decade I spent writing this book, my two most important supports have been my husband, Garrel Pottinger, and my friend Karen Reeds. Although neither resorted to nagging, both made it clear that they would accept no excuses for my failing to complete the book.

I have, of course, taxed the patience and ingenuity of any number of librarians, archivists, and curators. Among these, I owe the greatest debt to Elizabeth Ihrig and Albert Kuhfeld of the Bakken Library and Museum of Electricity in Life, in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Without the material the Bakken staff provided while I was a fellow there in the summer of 1985, this project would not have amounted to much more than a speculative article or two. The support of the Bakken Fellowship program enabled me to make the discoveries in the primary sources that convinced me I was on solid historical ground.

The libraries of Cornell University, especially the History of Science collection, have proved invaluable, as have the collections of the National Library of Medicine, the Library of Congress, the New York Public Library, the Charcot Library of the Salpêtrière in Paris, the Saratoga County Historical Society in Ballston Spa, New York, the Center for the History of American Needlework, the Kinsey Institute at Indiana University, and the Saratoga Room collection on hydrotherapy and balneology at the Saratoga Springs (New York) Public Library.

As sources of inspiration and guidance I must acknowledge Shere Hite of Hite Research, Joel Tarr of Carnegie-Mellon University, and my

former students at Clarkson University in Potsdam, New York, especially my Great Ideas in Western Culture students Marianne Incerpi and Gary Cassier. James Glynn III of Comtech, Incorporated, provided valuable insights into why so many people find this subject disturbing. Participants in seminars and meeting sessions asked important questions that needed answers at the 1986 meeting of the Society for the History of Technology at Queens University in Kingston, Ontario, the University of Ottawa Hannah Lectures in the History of Medicine series, and the Cornell University Humanities Colloquium. Joani Blank of Down There Press and Good Vibrations in California provided useful material on early vibrators and has been a consistent source of encouragement, as was Dell Williams of Eve’s Garden in New York City.

I owe a debt of gratitude to Robert J. Whelchel of Tri-State University and James Brittain of the Georgia Institute of Technology for their courageous decision to publish my article “Socially Camouflaged Technologies: The Case of the Electromechanical Vibrator,” in the July 1989 issue of the IEEE’s

Technology and Society

.

My editors and reader at the Johns Hopkins University Press deserve credit for their courage and sensitivity, as well: series editor Merritt Roe Smith, history editor Bob Brugger, reader Ruth Schwartz Cowan, Sarah Cline of the acquisitions department, marketing manager Hilary Reeves, and production editor Kimberly Johnson. Alice Bennett provided the kind of meticulous copyediting which all authors should have and aren’t capable of doing for themselves.

Gretchen Aguiar put a mind-numbingly long bibliography into a format that made it possible to find the references I needed when I needed them. Last but definitely not least, I doubt I would have found the courage to persist in my eccentricities, especially this one, had not my best friends cheered me on: Catherine Gatto Oliver, Judith Ruszkowski, Karen La Monica, and of course my mother, Natalie L. M. Petesch.

THE

TECHNOLOGY

OF

ORGASM

1

THE JOB NOBODY WANTED

In 1653 Pieter van Foreest, called Alemarianus Petrus Forestus, published a medical compendium titled

Observationem et Curationem Medicinalium ac Chirurgicarum Opera Omnia

, with a chapter on the diseases of women. For the affliction commonly called hysteria (literally, “womb disease”) and known in his volume as

praefocatio matricis

or “suffocation of the mother,” the physician advised as follows:

When these symptoms indicate, we think it necessary to ask a midwife to assist, so that she can massage the genitalia with one finger inside, using oil of lilies, musk root, crocus, or [something] similar. And in this way the afflicted woman can be aroused to the paroxysm. This kind of stimulation with the finger is recommended by Galen and Avicenna, among others, most especially for widows, those who live chaste lives, and female religious, as Gradus [Ferrari da Gradi] proposes; it is less often recommended for very young women, public women, or married women, for whom it is a better remedy to engage in intercourse with their spouses.

1

As Forestus suggests here, in the Western medical tradition genital massage to orgasm by a physician or midwife was a standard treatment for hysteria, an ailment considered common and chronic in women. Descriptions of this treatment appear in the Hippocratic corpus, the works of Celsus in the first century

A.D

., those of Aretaeus, Soranus, and Galen in the second century, that of Äetius and Moschion in the sixth century,

the anonymous eighth- or ninth-century work

Liber de Muliebria

, the writings of Rhazes and Avicenna in the following century, of Ferrari da Gradi in the fifteenth century, of Paracelsus and Paré in the sixteenth, of Burton, Claudini, Harvey, Highmore, Rodrigues de Castro, Zacuto, and Horst in the seventeenth, of Mandeville, Boerhaave, and Cullen in the eighteenth, and in the works of numerous nineteenth-century authors including Pinel, Gall, Tripier, and Briquet.

2

Given the ubiquity of these descriptions in the medical literature, it is surprising that the character and purpose of these massage treatments for hysteria and related disorders have received little attention from historians.

The authors listed above, and others in the history of Western medicine, describe a medical treatment for a complaint that is no longer defined as a disease but that from at the least the fourth century

B.C.

until the American Psychiatric Association dropped the term in 1952, was known mainly as hysteria.

3

This purported disease and its sister ailments displayed a symptomatology consistent with the normal functioning of female sexuality, for which relief, not surprisingly, was obtained through orgasm, either through intercourse in the marriage bed or by means of massage on the physician’s table. I shall place this disease paradigm in the context of androcentric definitions of sexuality, which explain both why such treatments were socially and ethically permissible for doctors and why women required them. Androcentric views of sexuality, and their implications for women and for the physicians who treated them, shaped the development not only of the concept of female sexual pathologies but also of the instruments designed to cope with them.

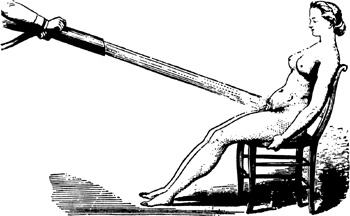

Technology tells us much about the social construction of the tasks and roles it is designed to implement. Although massage instrumentation has had many medical uses in history, I am concerned here only with its role in the treatment of a certain class of “women’s complaints.” The vibrator and its predecessors in the history of medical massage technologies are the means by which I shall examine three themes: androcentric definitions of sexuality and the construction of ideal female sexuality to fit them; the reduction of female sexual behavior outside the androcentric standard to disease paradigms requiring treatment; and the means by which physicians legitimated and justified the clinical production of orgasm in women as a treatment for these disorders. In evaluating these technologies, the perspective of gender is significant: for example,

men typically react to

figure 1

by wincing, and women laugh. Clearly, where technologies impinge on the body, especially its sexual organs, the sex of the body matters.

When the vibrator emerged as an electromechanical medical instrument at the end of the nineteenth century, it evolved from previous massage technologies in response to demand from physicians for more rapid and efficient physical therapies, particularly for hysteria. Massage to orgasm of female patients was a staple of medical practice among some (but certainly not all) Western physicians from the time of Hippocrates until the 1920s, and mechanizing this task significantly increased the number of patients a doctor could treat in a working day. Doctors were a male elite with control of their working lives and instrumentation, and efficiency gains in the medical production of orgasm for payment could increase income. Physicians had both the means and the motivation to mechanize.

The demand for treatment had two sources: the proscription on female masturbation as unchaste and possibly unhealthful, and the failure of androcentrically defined sexuality to produce orgasm regularly in most women.

4

Thus the symptoms defined until 1952 as hysteria, as well as some of those associated with chlorosis and neurasthenia, may have been at least in large part the normal functioning of women’s sexuality in a patriarchal social context that did not recognize its essential difference from male sexuality, with its traditional emphasis on coitus. The historically androcentric and pro-natal model of healthy, “normal” het-erosexuality is penetration of the vagina by the penis to male orgasm. It has been clinically noted in many periods that this behavioral framework fails to consistently produce orgasm in more than half of the female population.

5

Because the androcentric model of sexuality was thought necessary to the pro-natal and patriarchal institution of marriage and had been defended and justified by leaders of the Western medical establishment in all centuries at least since the time of Hippocrates, marriage did not always “cure” the “disease” represented by the ordinary and uncomfortably persistent functioning of women’s sexuality outside the dominant sexual paradigm. This relegated the task of relieving the symptoms of female arousal to medical treatment, which defined female orgasm under clinical conditions as the crisis of an illness, the “hysterical paroxysm.” In effect, doctors inherited the task of producing orgasm in women because it was a job nobody else wanted.

F

IG

. 1. French pelvic douche of about 1860 from Fleury, reproduced from Siegfried Giedion,

Mechanization Takes Command

(New York: Oxford University Press, 1948).

There is no evidence that male physicians enjoyed providing pelvic massage treatments. On the contrary, this male elite sought every opportunity to substitute other devices for their fingers, such as the attentions of a husband, the hands of a midwife, or the business end of some tireless and impersonal mechanism.

6

This last, the capital-labor substitution option, reduced the time it took physicians to produce results from up to an hour to about ten minutes.

7

Like many husbands, doctors were reluctant to inconvenience themselves in performing what was, after all, a routine chore. The job required skill and attention; Nathaniel Highmore noted in 1660 that it was difficult to learn to produce orgasm by vulvular massage. He said that the technique “is not unlike that game of boys in which they try to rub their stomachs with one hand and pat their heads with the other.”

8

At the same time, hysterical women represented a large and lucrative market for physicians. These patients neither recovered nor died of their condition but continued to require regular treatment.

Russell Thacher Trail and John Butler, in the late nineteenth century, estimated that as many as three-quarters of the female population were “out of health,” and that this group constituted America’s single largest market for therapeutic services.

9

Furthermore, orgasmic treatment could have done few patients any harm, whether they were sick or well, thus contrasting favorably with such “heroic” nineteenth-century therapies as clitoridectomy to prevent masturbation.

10

It is certainly not necessary to perceive the recipients of orgasmic therapy as victims: some of them almost certainly must have known what was really going on.

11

THE ANDROCENTRIC MODEL OF SEXUALITY

The androcentric definition of sex as an activity recognizes three essential steps: preparation for penetration (“foreplay”), penetration, and male orgasm. Sexual activity that does not involve at least the last two has not been popularly or medically (and for that matter legally) regarded as “the real thing.”

12

The female is expected to reach orgasm during coitus, but if she does not, the legitimacy of the act as “real sex” is not thereby diminished.

13

That more than half of all women, possibly more than 70 percent, do not regularly reach orgasm by means of penetration alone has been brought to our attention by researchers such as Alfred Kinsey and Shere Hite, but the fact was known, if not well publicized, in previous centuries.

14

This majority of women have traditionally been defined as abnormal or “frigid,” somehow derelict in their duty to reinforce the androcentric model of satisfactory sex.

15

These women may constitute most of the hysterics of history, whose numbers make plausible Thomas Sydenham’s argument in the seventeenth century that hysteria was “the most common of all diseases except fevers.”

16

It also explains the contention of nineteenth-century doctors that hysteria was pandemic in their time.

17

When marital sex was unsatisfying and masturbation discouraged or forbidden, female sexuality, I suggest, asserted itself through one of the few acceptable outlets: the symptoms of the hysteroneurasthenic disorders.