The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England (62 page)

Read The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Ian Mortimer

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Renaissance, #Ireland

History is not really about the past; it is about understanding mankind over time. Within that simple, linear story of change and survival there are a thousand contrasts, and within each of those contrasts there is a range of experiences, and if we put our minds to it, we can relate to each one. Such a multidimensional picture of the human race is a far more profound one than an understanding based on a reading of today’s newspapers: the image of mankind in the mirror of the moment is a relatively superficial one. Indeed, it is only through history that we can see ourselves as we really are. It is not enough to study the past for its own sake, to work out the facts; it is necessary to see the past in relation to ourselves. Otherwise studying the past is merely an academic exercise. Don’t get me wrong: such exercises are important – without them we would be lost in a haze of uncertainty, vulnerable to the vagaries of well-meaning amateurs and prejudicial readings of historical evidence – but sorting out the facts is just a first step towards understanding humanity over time. If we wish to follow the old Delphic command, ‘Mankind, know thyself’, then we need to look at ourselves over the course of history.

One last thought. It is often said of Shakespeare that he is ‘not of an age but for all time’ – a line originally penned by Ben Jonson. But Shakespeare

is

of an age: Elizabethan England. It makes him. It gives him a stage, a language and an audience. If Shakespeare is ‘for all time’, then so too is Elizabethan England.

The queen as she wants to be seen after 1588, with the victorious English fleet in the background and her hand resting on the New World. All later European queens will owe something to her model of powerful queenship.

The other face of the queen, laden with the burdens of her office. She stands apart from the throne, and is reflective and alone, holding an olive branch (for peace) as war with Spain looms.

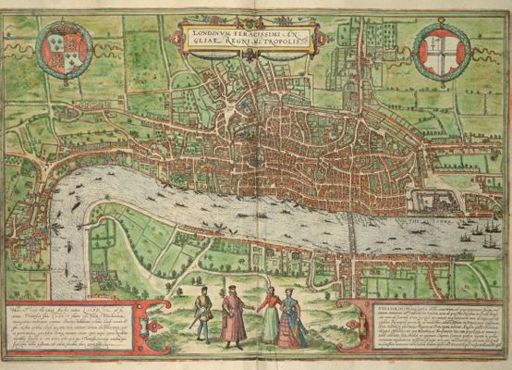

London, published in

Civitates Orbis Terrarum

(1572). The cathedral is shown with its spire intact, so this must have been engraved from pre-1561 sketches.

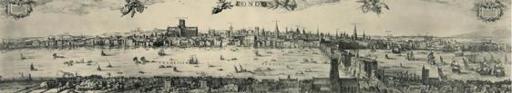

Claess Visscher’s view of London shows two of the Southwark theatres, the Swan (

far left

) and the Globe (

the righthand of the two theatres below St Paul’s

), as well as the Bear Garden. Notice also the skulls of traitors above Bridge Gate.

A fete at Bermondsey in 1569. The bright colours show people out in their best clothes and new ruffs, listening to the music, smelling the roast meat and watching the procession.

Bess of Hardwick, countess of Shrewsbury, as a young woman, in the relatively modest attire of the 1550s.

The fashionable Elizabeth Knollys, Lady Layton, in 1577. Note her Spanish sleeves, high-brimmed hat with dyed feather and hatband, and very fine ruff.

Lady Mary Fitzalan here wears a train gown over a Spanish farthingale, with an elaborately woven forepart beneath: a fashion from the start of the reign that proves remarkably enduring.

Elizabeth Buxton, painted by Robert Peake, c.1588–90. She wears a gown with French farthingale and French sleeves, and an elaborately worked stomacher over her tightly corseted waist.

Nonsuch Palace, built by Henry VIII, is still regarded as the most remarkable building in England and a must-see sight for Continental tourists. Above, the queen is arriving by coach; townswomen, fishwives and a water carrier are shown in the foreground.