The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England (65 page)

Read The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Ian Mortimer

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Renaissance, #Ireland

Primero is one of the most popular card games. If you are invited to take a hand, it will cost you – especially if you play with the queen, who loves to gamble and always seems to win.

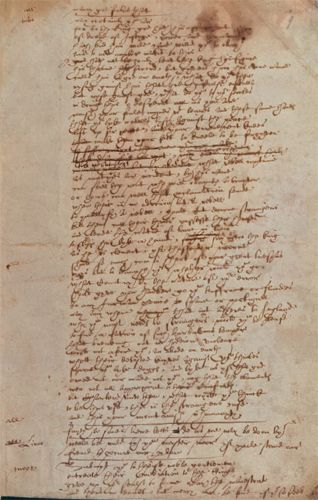

An example of secretary hand, the script that most well-educated people use. However, this is not just any example; it is an addition to Anthony Munday’s play

Sir Thomas More

, in the handwriting of William Shakespeare.

Notes

Introduction

1

. The story of William Hacket is to be found in Richard Cosin, A

conspiracie for pretended reformation

(1592). I came to this piece after reading Alexandra Walsham’s article on the events of 16 July 1591. See Walsham, ‘Hacket’.

2

.

Eliz. People

, p. 45, quoting Conyers Read,

Mr Secretary Cecil and Queen Elizabeth

(1955), p. 124.

3

. With reference to ‘the most powerful Englishwoman in history’, Elizabeth personally ruled over England and had huge influence over the entire anti-Catholic community of Europe. This personal rule, not subject to the pope, is the reason for saying she was the most powerful woman in British history. While Anne, Victoria and Elizabeth II all ruled over greater dominions, they were supported and controlled by a constitution that allowed them very little direct power. The power lay rather with the constitution that supported the monarchy, not in their own control of it. As for Margaret Thatcher, no elected secular politician can possibly have the authority of a hereditary and divinely appointed monarch, who can redirect the faith of the kingdom. A modern political leader simply has bigger bombs and better surveillance at her disposal.

1. The Landscape

1

. These figures are based on an area of 50,337 square miles for England and the population estimate of 2,984,576 for 1561 in Wrigley & Schofield, p. 528. The modern population figure is the 2008 estimate by the Office for National Statistics of 51,460,000.

2

. The regular layout of Stratford’s centre still reflects its charter of 1196, which stipulated that all the tenements or burgage plots should be a standard 3½ × 12 perches (57¾ feet × 198 feet). See Bearman,

Stratford

, p. 37.

3

. Jones,

Family

, pp. 22–3.

4

. Platt,

Rebuildings

, p. 20, quoting Harrison’s

Description

.

5

. Dyer, ‘Crisis’, p. 90.

6

. Wilson, ‘State’, p. 11. For modern research into the number of market towns, see the ‘Gazetteer of

Markets and Fairs in England and Wales to 1516: Full Introduction, table 2’, maintained by the Centre for Metropolitan History, available online freely at

http://www.history.ac.uk/cmh/gaz/gazweb2.html

. This states that 675 of the 2,022 markets granted or functioning prior to 1516 were still active in 1600, one less than Wilson.

7

. Vanessa Harding has suggested that the population, which most historians agree reached 55,000 in 1524 and 200,000 in 1600, could have reached 75,000 by 1550. See Harding, ‘London’, p. 112.

8

. Sacks, ‘Ports’, p. 383.

9

. Sacks, ‘Ports’, p. 384, using table 7.1 in E. A. Wrigley, ‘Urban growth and agricultural change: England and the continent in the early modern period’,

Journal of Interdisciplinary History

, 15 (1985).

10

. England’s coastline (not including any of its numerous islands) is about 5,581 miles long, and Wales, including Anglesey and Holyhead, is 1,680 miles long, a combined total of 7,261 miles. The total coastline of the kingdom of Denmark and Norway is in the region of 20,000 miles. Greece and Italy, which both have long coastlines, were not political states in their own right in the sixteenth century, Greece being part of the Ottoman Empire and Italy a series of smaller states. Spain’s coastline is about 3,100 miles long, as is that of Iceland; France’s is about 2,140 miles.

11

. In addition to the 336,000 in the table, my own rough estimates are as follows. The next sixty largest towns (with 2,500–6,000 people in 1600, and an average of about 3,000) represent another 180,000 citizens. The next hundred towns (of 2,000–2,500, average 2,200) are home to another 220,000. About two hundred towns have populations of 1,000–2,000 (300,000); and the approximately three hundred remaining towns with 500–1,000 inhabitants (average 700) represent about 210,000 more. This total means that 1.2 million people, out of a population of 4.11 million, were living in towns (29 per cent). Checking this against the

Cambridge Urban History

figures, which are most detailed for the 1660s onwards, even the rural south-west had achieved an overall proportion of 26 per cent by 1660 (see Jonathan Barry, ‘South-West’, in

CUH

, p. 68). A proportion of one in four is reasonable for 1600. For the medieval figures, see Mortimer,

TTGME

, p. 11 and note 3 on pp. 293–4. Note that the rise in urban populations was not a constant. In the early sixteenth century there was a significant downturn in the prosperity and size of the major towns.

12

. Villeinage still survived as a description of status in 1 per cent of the population. See Black,

Reign

, p. 251. A rare example of it having legal force is published in

DEEH

, p. 126.

13

. Wilson, ‘State’, p. 11.

14

. Hoskins,

Landscape

, p. 139.

15

. For the role of towns in supplying their hinterlands, see Mortimer, ‘Marketplace’.

16

.

Tudor Tailor

, p. 9, quoting B. Fagan,

The Little Ice Age

(New York, 2000).

17

. Dyer, ‘Crisis’, p. 89.

18

. M. A. Havinden, ‘Agricultural Progress in Open-Field Oxfordshire’,

Agricultural History Review

, 11 (1961), 73–83, at p. 73; Mortimer,

Glebe

, pp. ix, xxviii; Ross Wordie (ed.),

Enclosure in Berkshire 1485–1885

, Berkshire Record Society, vol. 5 (2000), p. xvii.

19

. These figures are adapted from those of Gregory King, computed at the end of the seventeenth century, given in Thirsk,

Documents

, p. 779. Hoskins,

Landscape

, p. 139, calculated that the woodland in the early sixteenth century must have been a million acres greater than in King’s day (a total of four million acres). The million acres of lost woodland were probably mostly put to pasture and parkland by 1695, so this area has been deducted from those totals. The amount of arable was probably within 500,000 acres of King’s estimate, as that which had been turned into parkland by 1695 is very unlikely to have all been taken from arable. Besides, many enclosures of arable fields would have resulted in consolidated arable holdings, not just pasture, and thus be included as arable by King. The figure for Berkshire waste is from Hoskins,

Landscape

, p. 141.

20

. Black,

Reign

, p. 237. The other major exports included in that 18.4 per cent were lead, tin, corn, beer, coal and fish.

21

. This is the number estimated for the sheep population of England in 1500. Hoskins,

Landscape

, p. 137.

22

. Rowse,

Structure

, p. 97; Dawson,

Plenti & Grase

, p. 85. Thomas Platter notes that the heaviest sheep he sees on his journey weigh 40–60lbs. See Platter,

Travels

, p. 185.

23

. Hoskins,

Landscape

, p. 138.

24

. Damian Goodburn, ‘Woodworking aspects of the Mary Rose’, in Marsden,

Noblest Shippe

, p. 68.

25

. For the Acts, see 1 Elizabeth, cap. 15; 23 Elizabeth, cap. 5; 27 Elizabeth, cap. 19. For prices, see Overton, ‘Prices’, esp. tables 6.1 (cupboards), 6.5 (bedsteads and coffers), 6.8 and 6.9 (coffers) and 6.11 (all wood).

26

. Williams,

Life

, p. 40 (Warwickshire); Hoskins,

Landscape

, p. 154 (Leicestershire).

27

. Tim Carder,

Encyclopaedia of Brighton

(1990), quoting Brighton’s ‘Book of Auncient Customs’.

28

. For the expansion of fishing in the south-east, see

CUH

, p. 54.

29

. See Magno, esp. p. 147.

30

. Emmison,

HWL

, pp. 290–3.

31

. Hoskins, ‘Towns’, p. 5.

32

. Platter,

Travels

, p. 153.

33

. Machyn,

Diary

, p. 259.

34

. For the prohibition of houses within three miles, see 35 Elizabeth I, cap. 6. For the spread of housing:

DEEH

, p. 46.

35

. Simon Thurley, ‘The Lost Palace of Whitehall’,

History Today

, 48, 1 (January 1998).

36

. Platter,

Travels

, pp. 153–4.

37

. In the order they appear in Stow,

Survay

, these are: (1) Portsoken, (2) Tower Street, (3) Aldgate, (4) Lime Street, (5) Bishopsgate, (6) Broad Street, (7) Cornhill, (8) Langbourn, (9) Billingsgate, (10) Bridge Within, (11) Candlewick Street, (12) Walbrook, (13) Dowgate, (14) Vintry, (15) Cordwainer Street, (16) Cheap, (17) Coleman Street, (18) Basinghall, (19) Cripplegate, (20) Aldersgate, (21) Farringdon Within, (22) Bread Street, (23) Queenhithe, (24) Castle Baynard, (25) Farringdon Without and (26) Bridge Without (including Southwark).

38

. Schofield, ‘Topography’, p. 300.

39

. Magno, p. 142.

40

. Machyn,

Diary

, p. 263.

41

. 24 Henry VIII, cap. 11 (Strand); 25 Henry VIII, cap. 8 (Holborn High Street).

42

. All the cries mentioned here are from plates 26 and 27

reproduced in Picard,

London

.

43

. Nicoll,

Elizabethans

, p. 49, quoting W. Burton, ‘The Rowsing of the Sluggard’.

44

. Orlin, ‘Disputes’, at p. 347. Houses of six storeys are visible in several early seventeenth-century woodcuts and engravings of the city and are specified in Ralph Tressell’s surveys.

45

. For sales of fish in Old St Paul’s, see Holmes,

London

, p. 41.

46

. As often noted, the stories of the drinking club at The Mermaid attended by Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, John Donne etc. are somewhat romantic. However, the landlord, William Johnson, was a friend and business partner of Shakespeare’s, for they both took part in what proved to be Shakespeare’s last property investment in 1613. See Schoenbaum,

Shakespeare

, p. 208.

2. The People

1

. According to Wrigley & Schofield, p. 528, the greatest compound annual growth rate for the sixteenth century was 1.13 in 1581–6. This was not equalled until 1786–90, when it reached 1.20. By then the population was well in excess of seven million.

2

. William Lambarde’s charge at the commission for almshouses, etc., at Maidstone, 17 January 1594, in Conyers Read (ed.),

William Lambarde and Local Government

, p. 182 (quoted in

Eliz. People

, p. 47).

3

. Carew,

Survey

, f. 37v.

4

. Wrigley & Schofield, pp. 229, 383, 399–400, 425, 477; Laslett,

WWHL

, p. 15. This model omits the factor of migration to the towns and the increase in real wages due to the increased manufacturing that accompanies increased urbanisation, which is another reason for the rise in wage rates and the independence of men who otherwise would have been in service of some sort or other. See Wrigley & Schofield, esp. p. 477.