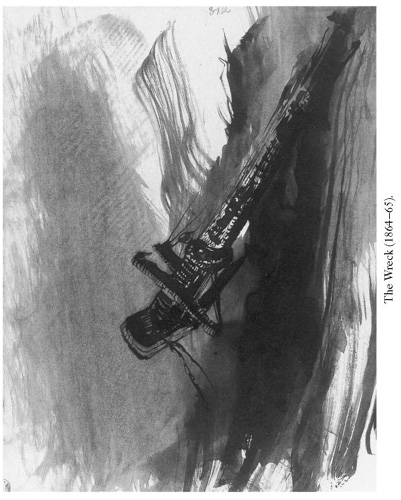

The Toilers of the Sea (35 page)

BOOK III

THE STRUGGLE

I

EXTREMES MEET AND CONTRARY FORESHADOWS CONTRARY

Nothing is more threatening than a late equinox.

There is an alarming phenomenon on the sea that could be called the arrival of the winds from the ocean. At any time of year, but particularly at the time of the syzygies,

182

when it is least to be expected, a strange tranquillity comes over the sea. The tremendous perpetual movement subsides; there is an air of somnolence; the sea becomes languid; it seems about to take a respite; it looks tired. All the flags worn by shipping, from the fishing boat's streamer to the warship's ensign, hang limply on the masts. The admiral's pennant and royal and imperial banners all sleep.

Suddenly the flags begin to flutter gently. This is the time, if there are clouds, to watch for the formation of banks of cirrusâif the sun is setting, to observe the reddening evening skyâif it is night and there is a moon, to study its haloes.

This is the time, too, when the captain or squadron commander, if he is fortunate enough to possess one of those storm glasses whose inventor is unknown, looks at his glass under the microscope and takes precautions against the south wind if the solution has the appearance of melted sugar and against the north wind if it breaks down into crystallizations resembling fern brakes or fir woods. And this is the time when, after consulting some mysterious gnomon engraved by the Romans, or by demons, on one of those enigmatic standing stones known in Brittany as menhirs and in Ireland as cruachs, the poor Irish or Breton fisherman hauls his boat ashore.

Meanwhile, the serenity of the sky and of the ocean persists. Day breaks radiantly and the dawn smiles. This was what filled the ancient poets and seers with religious horror, appalled as they were that the sun should be thought to be false.

Solem quis dicere falsum audeat?

183

The somber vision of a latent possibility is denied to man by the fatal opacity of material things. The most redoubtable and most perfidious of aspects is the mask of the abyss. We say “an eel under a rock”:

184

we should say “storm under calm.”

Hoursâsometimes daysâmay pass in this way. Pilots train their telescopes this way and that. The faces of old sailors take on an air of severity, reflecting their hidden anger as they wait in suspense.

Suddenly a great confused murmuring is heard. There is a kind of mysterious dialogue in the air, but nothing is to be seen. The vast expanse remains impassive.

Meanwhile the noise increases, becomes louder, rises in tone. The dialogue becomes more distinct.

There is someone beyond the horizon.

Someone terrible: the wind.

The wind: that is to say, the rabble of titans that we call sea breezes. The immense canaille of the shadows.

They were known in India as the marouts, in Judaea as the cherubim, in Greece as the aquilons. They are the invincible birds of prey of the infinite. These northerly winds are coming up fast.

II

THE WINDS FROM THE OCEAN

Where do they come from? From the incommensurable. Their wingspan takes up the whole expanse of the gulf of ocean. Their giant wings need the illimitable distances of the solitary wastes. The Atlantic, the Pacific, those vast blue open spaces: that is what suits them best. They darken the skies. They fly there in great troupes. Commander Page once saw seven waterspouts at the same time on the open sea. They are there in all their wildness. They premeditate disasters. Their business is to foment the ephemeral and eternally continuing swelling of the waves. What they can do is unknown; what they want is hidden from us. They are the sphinxes of the abyss, and Vasco da Gama is their Oedipus. They appear in the obscurity of the ever-moving expanse of ocean, the faces of the clouds. Those who catch sight of their pale lineaments in that wide dispersion that is the horizon of the sea feel themselves in presence of an irreducible force. It seems as if human intelligence upsets them, and they bristle with hostility to it. Intelligence is invincible, but this element is impenetrable. What can be done against this impalpable ubiquity? Wind turns into a club, and then becomes wind again. The winds fight an enemy by crushing him and defend themselves by vanishing. Those who encounter them, disconcerted by their varied plan of attack and swiftly repeated blows, are reduced to expedients. They withdraw as much as they attack. They are impalpable, but tenacious. How can they be overcome? The prow of the

Argo,

carved from an oak tree from Dodona, was both prow and pilot: it spoke to them. But they maltreated it, goddess though it was. Columbus, seeing them approaching the

Pinta,

stood up on deck and addressed the first verses of Saint John's Gospel to them. Surcouf 185 insulted them, saying: “Here comes the gang!” Napier

186

fired his cannon at them. They exercise a dictatorship of chaos.

They possess this chaos. What do they do with it? Implacable deeds: we know not what. The den of the winds is more monstrous than a lions' den. How many corpses there are in its deep recesses! The winds drive this great obscure and bitter mass pitilessly onward. We hear them always, but they listen to no one. They commit acts resembling crimes. We know not whom they are attacking with these white flecks of foam. What impious ferocity there is in bringing about a shipwreck! What an affront to Providence! They seem sometimes to be spitting on God. They are the tyrants of the unknown places.

Luoghi spaventosi,

as the seamen of Venice used to murmur.

The trembling expanses of sea suffer assault and battery at their hands. What happens in these great wastes cannot be expressed. Some mysterious horseman is concealed amid the shadows. There is the noise of a forest in the air. Nothing can be seen, but the sound of horses galloping is heard. It is midday, and all at once it is night; a tornado sweeps past; it is midnight, and suddenly it is broad daylight; the emanations of the Pole are illuminated. Whirlwinds pass to and fro, reversing their direction in a kind of hideous dance: the trampling of plagues on the water. An overheavy cloud breaks in two and falls in pieces into the sea. Other clouds, purple-tinged, flash and rumble, then turn dark and somber; the cloud, emptied of its thunder, blackens like an extinguished ember. Sacks of rain burst open and dissolve into mist. Here there is a furnace amid falling rain, there a wave emitting flame. The white gleam of the sea beneath the rain reflects light on astonishing distant vistas; in the depths, constantly changing, can be seen vaguely recognizable forms. Monstrous navels open up in the clouds. Vapors swirl around, the waves pirouette; naiads, drunk, tumble about; as far as the eye can see the massive sluggish sea is in movement, but moving nowhere; everything is livid; from the pallor emerge desperate cries.

In the depths of the inaccessible darkness great sheaves of shadow quiver. Every now and then there is a paroxysm. The noise grows into a tumult, as the waves grow into a swell. The horizon, a confused superposition of waves, an endless oscillation, murmurs in basso continuo; there are weird outbreaks of noise; there are sounds like the sneezing of hydras.

Cold winds blow up, then hot winds. The shuddering of the sea reflects a fear of some terrible happening. Disquiet; anguish; the profound terror of the waters. Suddenly the hurricane comes, like a wild beast, to drink in the ocean; there is an extraordinary suction; the water rises to the invisible mouth, a sucker takes shape, the tumor swells; there is a waterspout, the fiery whirlwind of the ancients, a stalactite above and a stalagmite below, a double upturned cone revolving, one point balanced on another, a kiss between two mountains, a mountain of foam rising and a mountain of cloud descending; a fearful coitus between the waves and the shadows. The waterspout, like the column of fire in the Bible, is dark during the day and luminous at night. In the face of the waterspout the thunder is silent, as if afraid.

There is a whole gamut in the vast confusion of the solitudes, a redoubtable crescendo: the shower of rain, the blast, the squall, the gale, the storm, the tempest, the waterspout; the seven strings in the lyre of the winds, the seven notes of the abyss. The sky is a wide expanse, the sea a rounded surface; a breath of wind passes, then there is a sudden change, and all is fury and confusion.

Such are these harsh regions.

The winds run, fly, swoop down, die away, rise again, whistle, roar, laugh; frantic, lascivious, unbridled, taking their ease on the irascible waves. They howl, but their howling has a certain harmony. They fill the sky with sound. They blow on the clouds as on a brass instrument, they raise space to their lips, and they sing in the infinite, with all the mingled voices of clarions, horns, oliphants, bugles, and trumpets, in a kind of Promethean fanfare. Any who hear them are listening to Pan. The fearful thing is that they are playing. They are filled with a colossal joy made up of shadows. In these solitudes they hunt down ships. Unceasingly, day and night, at any time of year, in the Tropics as at the Pole, blowing their wild trumpets, they pursue through the entanglements of clouds and waves the great black hunt after shipwrecks. They are the masters of hounds. They are enjoying themselves. They urge on their hounds to bark at the rocks and the waves. They drive the clouds together and tear them apart. They knead, as with millions of hands, the supple immensity of water.

Water is supple because it is incompressible. When pressed it slips away again. Put under compulsion on one side, it escapes on the other. It is thus that water becomes waves. The waves are its form of freedom.

III

EXPLANATION OF THE SOUND HEARD BY GILLIATT

The great descent of the winds on the earth takes place at the equinoxes. At these times the balance between the Tropics and the Pole swivels and the colossal tide of the atmosphere directs its flow on one hemisphere and its ebb on the other. There are constellations that symbolize these phenomena, the Balance and the Water Carrier.

This is the season for storms.

The sea waits, and keeps silent.

Sometimes the sky has an unhealthy look. It is pale, and a dark veil obscures its face. Seamen are worried when they see the ill humor of the shadows.

But they are most afraid when the shadows seem contented. A smiling sky at the equinox is a storm concealing its iron hand in a velvet glove. When the sky was in this mood the Weepers' Tower

187

in Amsterdam was filled with women scanning the horizon.

When the spring or autumn storms are late in coming they accumulate greater force. They are storing up greater resources for creating havoc. Beware of arrears! Ango

188

used to say: “The sea is good at settling her accounts.”

When there is too long a wait the sea betrays its impatience only by greater calm; but the magnetic tension is shown by what might be called the inflammation of the water. Lights are emitted by the waves; the air is electric, the water phosphoric. Seamen feel harassed. This moment is particularly perilous for ironclads; their iron hull can produce wrong compass directions and lead them to destruction. The transatlantic steamer

Iowa

perished in this way.

For those who are on familiar terms with the sea, its aspect at such moments is strange; it is as if it desired and at the same time feared the cyclone. Some nuptials, though strongly desired by nature, are received in this fashion. The lioness in heat flees from the lion's pursuit. The sea, too, is in heat: hence its trembling motion.

This immense union is about to be consummated. And this mating, like the marriages of the ancient emperors, is celebrated by immolations. It is a festival given piquancy by disasters.

Meanwhile, from over yonder, from the open sea, from those unreachable latitudes, from the livid horizon of these solitary wastes, from the depths of the ocean's boundless freedom, the winds are approaching.

Beware! This is the equinox.

A tempest is the result of a conspiracy. Ancient mythology glimpsed these indistinct personalities mingled with the whole diffused substance of nature. Aeolus was seen as conspiring with Boreas. Agreement between the one element and the other is necessary.

They share out the task between them. Impulsions have to be given to the waves, to the clouds, to the emanations; night is an auxiliary, and use must be made of it. There are compasses to be led astray, beacons to be extinguished, lighthouses to be masked, stars to be hidden. The sea must cooperate in all this. Every storm is preceded by a murmuring. Beyond the horizon there are the preliminary whisperings of hurricanes.

This is the sound that is heard in the darkness, far away, over the terrified silence of the sea. It was this dread whispering that Gilliatt had heard. The phosphorescence had been the first warning, the murmuring the second.

If the demon Legion exists, it is he, undoubtedly, that is the Wind.

The wind is multiple, but air is of one substance. In consequence all storms are mixed. The unity of air requires it.

The whole of the abyss is involved in a tempest. The entire ocean is in a squall. All its forces are mobilized and take part in the action. A wave is the gulf below, a gust of wind the gulf above. In facing a gale you are facing the whole of the sea and the whole of the sky. Messier,

189

the great naval expert, the thoughtful astronomer in his cottage at Cluny, said: “The wind from everywhere is everywhere.” He did not believe that winds could be imprisoned, even within landlocked seas. In his view there were no purely Mediterranean winds. He claimed to be able to recognize them in their passage. He declared that on one day, at such and such an hour, the foehn of Lake Constance, the ancient Favonius of Lucretius, had crossed the horizon of Paris; on another day the bora of the Adriatic; on another the gyratory Notus that is said to be confined to the circle of the Cyclades. He specified their various emanations. He did not think that the autan that blows between Malta and Tunis and the autan that blows between Corsica and the Balearics were unable to escape from these bounds. He did not accept that winds could be confined in cages like bears. He said: “All rain comes from the Tropics and all lightning comes from the Poles.” For winds become saturated with electricity at the intersection of the meridians of the celestial sphere, which mark the ends of the earth's axis, and with water at the equator, bringing liquid from the Line and fluid from the Poles.

Ubiquity is the name of wind.

This does not mean, of course, that there are no particularly windy zones. Nothing has been more clearly demonstrated than the existence of such continuously blowing currents of air; and one day aerial navigation, using ships of the airâwhich in our mania for Greek terms we call aeroscaphsâwill make use of the principal lines of this kind. The canalization of the air by the winds is beyond doubt; there are rivers of wind, streams of wind, and brooks of wind. But the ramifications of the air operate in the inverse way from the ramifications of water: the brooks branch off from the streams and the streams from the rivers rather than flow into themâproducing dispersion in place of concentration.

It is this dispersion that creates the solidarity of the winds and the unity of the atmosphere. One molecule out of place will displace another. The whole of wind moves together. To these deeper causes of amalgamation are to be added the relief pattern of the globe, intruding into the atmosphere with all its mountains, creating knots and torsions in the course of the wind, and giving rise to countercurrents in all directions: boundless irradiation. The phenomenon of wind is the oscillation of two oceans, one upon the other: the ocean of air, superimposed on the ocean of water, rests on this constant motion and wavers over the trembling element below.

The indivisible cannot be broken up into compartments. There is no intervening wall between one wave and another. The Channel Islands feel impulses coming from the Cape of Good Hope. Shipping throughout the world is confronting a single monster. The whole of the sea is one hydra. The waves cover the sea with a kind of fish's skin. The Ocean is Ceto.

190

On this unity swoops down the innumerable.