The Toilers of the Sea (16 page)

V

WELL-EARNED SUCCESS ALWAYS ATTRACTS HATRED

At that time this was the state of Mess Lethierry's affairs: The Durande had fully lived up to her promise. Mess Lethierry had paid off his debts, repaired the breaches in his fortune, settled his accounts in Bremen, and paid his bills in Saint-Malo. He had cleared the mortgages on Les Bravées and redeemed all the small charges on the house. He was the owner of a valuable and productive capital asset, the Durande. The net annual income from the ship was a thousand pounds sterling and was still increasing. The Durande was in fact the sole source of his fortune. It also made the fortune of the district. Since the transport of cattle was the ship's main source of profit, it had been necessary, in order to improve the arrangements for the stowage of cargo and facilitate the loading and unloading of cattle, to dispense with the davits and the two dinghies. This was perhaps unwise. The Durande now had only one boat, the longboatâthough this was an excellent craft.

It was ten years since Rantaine had made off with Mess Lethierry's money.

The weak point in the Durande's success was that people had no confidence in it; it was thought to be merely a lucky chance. Mess Lethierry's prosperity was accepted, but it was regarded as an exception. He was seen as having embarked on a crazy scheme that had turned out well. Someone who had imitated him at Cowes, on the Isle of Wight, had failed, and the shareholders in the venture had been ruined. Lethierry said that this was because the ship was badly built. But people still shook their heads. New ideas suffer from the disadvantage that everyone is against them, and the slightest thing that goes wrong discredits them. One of the commercial oracles of the Norman archipelago, a banker named Jauge who came from Paris, was once consulted about investing money in steamships. He is said to have replied, turning his back on the enquirer: “The proposition you have in mind is a conversionâthe conversion of money into smoke.” Sailing ships, on the other hand, could find any number of people ready to invest in them. Capital was firmly in favor of canvas as against a boiler. On Guernsey the Durande was a fact, but steam was not a principle that people were ready to accept: so strong is the prejudice against progress. People said of Lethierry: “All right, it has turned out well; but he wouldn't do it again.” The example he had given did not encourage others but alarmed them. No one would have ventured on a second Durande.

VI

SHIPWRECKED MARINERS ARE LUCKY IN ENCOUNTERING A SLOOP

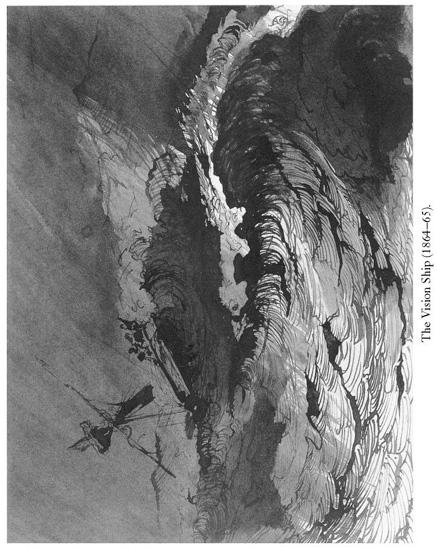

The equinox arrives early in the Channel. It is a narrow sea that hampers and irritates the wind. Westerly winds begin to blow in the month of February, and the waves are churned in all directions. Seafarers become apprehensive; the people of the coast keep an eye on the signal mast; there are worries about ships that may be in distress. The sea lies in ambush; an invisible bugle sounds, as if calling men to war; fierce gusts of air overwhelm the horizon; the wind increases in fury. The darkness is filled with whistling and howling. Far up in the clouds the black face of the storm puffs out its cheeks.

The wind is one danger; fog is another.

Seamen have always feared fog. Some fogs hold in suspension microscopic prisms of ice, to which Mariotte

117

attributed such effects as haloes, parhelia, and paraselenae. Fogs during a storm are composite; in them various vapors of differing specific gravity combine with water vapor, superimposed in an order that divides the fog into zones, giving it a regular structure; at the bottom is iodine, above this is sulfur, above this is bromine, and above this again is phosphorus. To some extent this structure, allowing for electrical and magnetic tension, explains a number of phenomenaâthe Saint Elmo's fire observed by Columbus and Magellan, the shooting stars raining down on ships of which Seneca speaks, the two flames called Castor and Pollux that are mentioned by Plutarch, the Roman legions whose javelins seemed to Caesar to be catching fire, the pike in Duino Castle in Friuli that sent out sparks when the sentry on duty touched it with his lance, and perhaps even the thunderings down below that the ancients called the “terrestrial lightnings of Saturn.” On the equator there seems to be a permanent band of mist around the globe, the cloud ring. The function of the cloud ring is to cool down the Tropics, as that of the Gulf Stream is to warm up the Pole. Under the cloud ring are the dangerous fogs. These are the horse latitudes, in which in past centuries sailors threw horses into the sea, with the object in stormy weather of lightening the ship and in calm weather of husbanding their water. Columbus said:

“Nube abaxo es muerte,”

“Low cloud is death.” The Etruscans, who were to meteorology what the Chaldeans were to astronomy, had two priesthoods, the priesthood of thunder and the priesthood of the clouds; the

fulguratores

observed lightning and the

aquileges

observed fog and mist. The college of priest-augurs of Tarquinia was consulted by the Tyrians, the Phoenicians, the Pelasgians, and all the primitive seamen of the ancient Mediterranean. They had some inkling of the way in which storms were generated; it is intimately connected with the method of generation of fog, and is indeed the same phenomenon. There are three foggy zones on the ocean: an equatorial zone and two polar zones: seamen give them the same name, the “black pot.”

In all waters, and particularly in the Channel, the equinoctial fogs are dangerous. They suddenly bring night over the sea. One of the dangers of fog, even when it is not particularly dense, is that it prevents sailors from recognizing changes in the seabed from changes in the color of the water, resulting in a dangerous concealment of approaching breakers or shallows. You can suddenly come on a reef without any warning. Frequently fog leaves a vessel with no alternative but to lay to or drop anchor. Fog causes as many shipwrecks as wind.

After a heavy gale that followed one of these days of fog the mail sloop

Cashmere

nevertheless arrived safely from England. It entered St. Peter Port at first light, just as Castle Cornet was firing its cannon to greet the sun. The sky had cleared. The

Cashmere

had been eagerly awaited, since it was believed to be bringing St. Sampson's new rector. Soon after its arrival the rumor spread in the town that during the night it had picked up a boat containing the crew of a vessel that had suffered shipwreck.

VII

A STRANGER IS LUCKY IN BEING SEEN BY A FISHERMAN

That night, when the wind died down, Gilliatt went out fishing, though without going too far from the coast.

Coming back on the rising tide about two o'clock in the afternoon, on a fine sunny day, as he was passing the Beast's Horn on his way to the creek at the Bû de la Rue, he thought he saw a shadow on the Seat of Gild-Holm-âUr, a shadow that was not the shadow of the rock. He brought his boat closer in and saw that there was a man sitting in the seat. The tide was already high and the rock was surrounded by the sea; escape was impossible. Gilliatt waved vigorously to the man, but he remained motionless. Gilliatt drew nearer. The man was asleep.

The man was dressed in black. “He looks like a priest,” Gilliatt thought. He drew closer still and saw that the man was quite young. The face was unknown to him.

Fortunately the rock fell steeply down to the sea and there was plenty of depth. Gilliatt moved close in and was able to come alongside the rock. The tide now brought the boat so high that Gilliatt, standing on the gunwale, could reach the man's feet. He stood to his full height and stretched up his hands. If he had slipped he would have had little chance of coming to the surface again. The waves were lashing the rock, and he would inevitably have been crushed between the boat and the rock.

He tugged the sleeping man's foot. “What are you doing here?”

The man woke up. “I have been enjoying the view,” he said.

A moment later, now wide awake, he went on: “I have just arrived on Guernsey, and took a walk along this way. I had spent the night at sea. I thought, What a beautiful view! I was tired, and I fell asleep.”

“Ten minutes more, and you would have been drowned,” said Gilliatt.

“Really?”

“Jump into my boat.”

Gilliatt kept the boat in position with his foot, clung to the rock with one hand, and held out the other to the young man in black, who sprang lightly into the boat. He was a very handsome young man.

Gilliatt took up the oars, and in two minutes the boat ran into the creek at the Bû de la Rue.

The young man wore a round hat and a white cravat. His long black frock coat was buttoned up to the neck. He had fair hair cut in the form of a tonsure, a rather feminine face, a clear eye, an air of gravity.

The boat had now run into land. Gilliatt passed the cable through the mooring ring and turned round, to see the young man holding out a golden sovereign in a hand of extreme whiteness.

Gilliatt put the hand gently aside.

There was a silence, which was broken by the young man.

“You have saved my life.”

“Maybe,” said Gilliatt.

The boat was now made fast, and they landed.

The young man continued:

“I owe you my life, sir.”

“What of that?”

There was a further silence.

“Are you of this parish?” asked the young man.

“No,” said Gilliatt.

“What parish do you belong to?”

Gilliatt raised his right hand, pointed to the heavens and said, “That one.”

The young man bowed, and left him. After walking a few paces he stopped, felt in his pocket, drew out a book, and returned to Gilliatt, holding out the book.

“Allow me to offer you this.”

Gilliatt took the book. It was a Bible.

A moment later Gilliatt, leaning on his garden wall, saw the young man turning the corner of the path leading to St. Sampson.

Gradually he lowered his head, forgot the stranger, forgot that the Seat of Gild-Holm-âUr existed. Everything else disappeared in his immersion in the depths of his reverie. This abyss of Gilliatt's was Déruchette.

He was roused from this shadowland by a voice calling his name:

“Hey there, Gilliatt!”

Recognizing the voice, he raised his eyes.

“What is it, Sieur Landoys?”

Sieur Landoys was driving along the road, a hundred paces from the Bû de la Rue, in his phaeton, drawn by his small horse. He had stopped to call to Gilliatt, but he seemed to be preoccupied and in a hurry.

“There is news, Gilliatt.”

“Where?”

“At Les Bravées.”

“What is it?”

“I'm too far away to tell you about it.”

Gilliatt felt a tremor.

“Is Miss Déruchette going to be married?”

“No. It's not that at all.”

“What do you mean?”

“Go to Les Bravées and you'll find out.”

And Sieur Landoys whipped up his horse.

BOOK V

THE REVOLVER

I

CONVERSATIONS AT THE INN

Sieur Clubin was a man who was always looking out for an opportunity.

He was small and sallow-faced and had the strength of a bull. The sea had never managed to give him a weather-beaten air. His flesh looked as if it were made of wax. He was the color of a wax candle, and there was the discreet glimmer of a candle in his eyes. He had a wonderfully retentive memory. If he had once seen a man he had him placed, as if he had made a note in a ledger. His laconic glance seized hold of you. His eye took in an image of a face and retained it; even if the face had aged, Sieur Clubin could recognize it. There was no deceiving this tenacious memory. Sieur Clubin was a man of few words, sober and cold in manner, with never so much as a gesture. His frank and open air won over everyone at once.

Many people thought he was naïve: there were creases at the corners of his eyes that gave him an extraordinarily simpleminded look. As we have said, there was no better seaman than Sieur Clubin; no one better at reefing a sail, at keeping a vessel to the wind or the sails well set. No one had a higher reputation for religion and integrity. Anyone who suspected him of any failing would himself have been suspect. He was friendly with Monsieur Rébuchet, the money changer in Rue Saint-Vincent in Saint-Malo, next door to the gunsmith. Monsieur Rébuchet used to say: “I would trust Clubin to look after my shop.”

Sieur Clubin was a widower. His wife had been an honest woman as he was an honest man. She had died with a reputation for unassailable virtue. If the bailiff had tried to trifle with her she would have reported him to the king. If the good Lord himself had been in love with her she would have told the curé. The couple, Sieur and Dame Clubin, were regarded in Torteval as the very epitome of the English virtue of respectability. Dame Clubin had the whiteness of the swan, Sieur Clubin of the ermine. He would have died from any spot on his coat. If he found a pin he would try to return it to its owner. If he had picked up a box of matches he would have proclaimed the fact around the town. One day he had gone into a tavern in Saint-Servan

118

and said to the owner: “I had lunch here three years ago, and you made a mistake in the bill,” handing over sixty-five centimes. He had a tremendous air of probity, with a watchful pursing of the lips.

He seemed always to be pointing like a game dog. Whom was he after? Probably rogues.

Every Tuesday he sailed the Durande from Guernsey to Saint-Malo. He arrived on the Tuesday evening, stayed there for two days to load his cargo and returned to Guernsey on the Friday morning.

In those days there was a little hostelry on the harbor at Saint-Malo, the Auberge Jean. It was pulled down when the present quays were built. At that time the sea came up to the Porte Saint-Vincent and the Porte Dinan. At low tide carts and light carriages ran between Saint-Malo and Saint-Servan, weaving their way between vessels lying high and dry, avoiding buoys, anchors, and cables and sometimes risking damage to their leather hoods from a low yard or a flying jib. Between high and low tides drivers whipped their horses over sand on which six hours later the wind was whipping up the waves. On these same sands there used to roam the twenty-four guard dogs of Saint-Malo, which in 1770 ate a naval officerâan excess of zeal that led to their demise. Nowadays you no longer hear nocturnal barking between the Grand Talard and the Petit Talard.

Sieur Clubin always stayed at the Auberge Jean, which housed the French office of the Durande.

The local customs officers and coastguards ate and drank in the Auberge Jean, where they had their own table. There the customs officers from Binic met the customs officers of Saint-Malo, to the advantage of the service.

The masters of ships also patronized the inn, but they ate at a separate table.

Sieur Clubin sometimes sat at one table, sometimes at the other; but he preferred the customs officers' table to the sea captains'. He was welcome at both.

The fare at these tables was excellent. There were all sorts of strange foreign drinks for seamen far from home. A dandyish young sailor from Bilbao could have had an

helada.

Stout was drunk as at Greenwich, and brown Gueuze beer as at Antwerp.

The captains of oceangoing vessels and shipowners sometimes appeared at the captains' table. There was much exchanging of news: “How are sugars doing?”â“You can only get refined sugar in small lots. But unrefined sugars are doing well; three thousand sacks from Bombay and five hundred barrels from Sagua.”â“You'll see: the conservatives will throw out Villèle.”â“And what about indigo?”â“There were only seven bales from Guatemala.”â“The

Nanine-Julie

has arrived. A fine three-master from Brittany.”â“The two towns on the River Plate

119

are quarreling again.”â“When Montevideo grows fat Buenos Aires grows thin.”â“They have had to tranship the cargo of the

Regina Coeli,

which has been condemned in Callao.”â“Cocoas are brisk; sacks of Caracas are quoted at two hundred and thirty-four, Trinidad at seventy-three.”â“I hear that at the review in the Champ de Mars there were shouts of âDown with the government.' ”â“Green salted Saladero hides are selling at sixty francs for ox hides and forty-eight for cow hides.”â“Have they got past the Balkans? What is Diebitsch doing?”â “At San Francisco there is a shortage of aniseed. Plagniol olive oil is quiet. Gruyère cheese in keg, thirty-two francs the hundredweight.”â “Well, is Leo XII

120

dead yet?Ӊand so on, and so on.

All these matters were discussed in a clamor of voices. At the table occupied by the customs officers and coastguards the conversation was conducted in more subdued tones. The business of policing the coasts and harbors calls for less noise and more restraint in conversation.

The captains' table was presided over by an old oceangoing master mariner, Monsieur Gertrais-Gaboureau. Monsieur Gertrais-Gaboureau was not a man: he was a barometer. His long experience of the sea had given him an extraordinary infallibility as a forecaster. He was accustomed to decree each day what the weather would be like on the following day. He sounded the winds; he felt the pulse of the tides. He said to the clouds: “Show me your tongue”âthat is, lightning. He was the physician of the waves, the breezes, the squalls. The ocean was his patient; he had gone around the world as a doctor conducts a clinic, examining each climate in its health and sickness; he thoroughly understood the pathology of the seasons. He could be heard making statements such as this: “Once in 1796 the barometer fell three lines below storm level.” He was a seaman from love of the sea, and hated England in proportion to that love. He had made a thorough study of the English navy in order to discover its weak points. He would explain how the

Sovereign

of 1637 differed from the

Royal William

of 1670 and the

Victory

of 1755. He compared their various superstructures. He regretted the towers on the decks and the funnel-shaped tops of the

Great Harry

of 1514, probably because they had offered such good targets for French gunners. Nations existed for him only in terms of their maritime institutions, and he referred to them by bizarre synonyms of his own devising. For him England was Trinity House, Scotland the Northern Commissioners, and Ireland the Ballast Board. He was a mine of informationâan almanac and an alphabetâa volume of tide tables and freight rates. He knew by heart the toll charges of lighthouses, particularly English lighthouses: a penny per ton for passing this one, a farthing per ton for passing that one. He would say: “The Small's Rock lighthouse, which used to use only two hundred gallons of oil, now burns fifteen hundred.” One day, when at sea, he had fallen gravely ill and was thought to be dead; with the crew surrounding his hammock, he had interrupted the death rattle to tell the ship's carpenter: “It would be a good idea to have on each side of the caps a sheave hole to house a cast-iron wheel with an iron axle that the mast ropes could run over.” A commanding character indeed.

The subject of conversation was seldom the same at the captains' and the customs officers' tables. But this is precisely what happened at the beginning of this month of February to which our tale has brought us. The three-master

Tamaulipas,

Captain Zuela, coming from Chile and returning there, attracted the interest of both tables. At the captains' table they discussed her cargo, at the customs men's table what she was up to.

Captain Zuela, who came from Copiapó, was a Chilean with a bit of Colombian blood who had fought in the wars of independence in an independent manner, sometimes on BolÃvar's side and sometimes on Morillo's, depending on which paid him best. He had grown rich by being of service to all. No one could be more of a Bourbon supporter than he, no one more of a Bonapartist, an absolutist, a liberal, an atheist, a Catholic. He belonged to that large party that could be called the Lucrative party. He turned up in France from time to time on some commercial business; and, if rumor spoke truly, he was happy to give passage on his ship to fugitives of all kindsâbankrupts, political refugees, it was all one to him, provided they paid. The embarkation process was quite simple. The fugitive waited at a lonely spot on the coast, and when his ship sailed Zuela sent a boat to pick him up. On his last voyage he had helped a fugitive from justice in the Berton case to escape, and this time he was said to be planning to carry men who had been involved in the Bidassoa affair.

121

The police had been alerted and had their eye on him.

This was a time of flights and escapes. The Restoration

122

was a period of reaction; and while revolutions lead to migrations, restorations bring proscriptions. During the seven or eight years after the return of the Bourbons there was widespread panicâin the financial world, in industry, in commerceâwhen men felt the earth shaking under them and there were numerous bankruptcies. In politics there was a general

sauve-qui-peut.

Lavalette had taken flight, Lefebvre-Desnouettes had taken flight, Delon had taken flight; special tribunals were dispensing ruthless punishment; and there was the case of Trestaillon. People avoided the bridge at Saumur, the esplanade in La Réole, the wall of the Observatory in Paris, the Tour de Taurias in Avignonâdismal landmarks of history that recalled the work of reactionary forces and still show the mark of their bloodstained hands. The trial of Thistle-wood in London, with its ramifications in France, and the trial of Trogoff in Paris, with its ramifications in Belgium, Switzerland, and Italy, had given rise to widespread grounds for anxiety and motives for flight, and had increased the great subterranean rout that decimated every rank, up to the highest, in the social order of the day.

123

To find a place of safety was the general care. To be suspected of rebellion meant ruin. The spirit of the special tribunals survived the tribunals themselves. Conviction was a matter of course. Suspects fled to Texas, the Rocky Mountains, Peru, Mexico. The men of the Loireâregarded as brigands then, as paladins nowâhad established the Champ d'Asile.

124

A song by Béranger put these words in their mouths:

Sauvages, nous sommes français; prenez pitié de notre gloire.

Self-banishment was their only resource. But nothing is less simple than to flee: this monosyllable contains abysses. Everything stands in the way of those seeking to escape. To avoid detection it is necessary to assume disguise. Men of some standing in the world, and indeed some illustrious personages, were reduced to expedients normally practiced only by criminals. Nor were they very good at it. They did not fit comfortably into their assumed identity. The freedom of movement to which they were accustomed made it difficult for them to slip through the meshes of escape. Encountering the police, a rogue on the run behaved with more propriety than a general; but imagine innocence compelled to play a part, virtue disguising its voice, glory wearing a mask! Some dubious-looking character might be a well-known figure in quest of a false passport. The aspect of a man trying to escape might be suspicious, but he might nevertheless be a hero. These are fugitive features characteristic of a particular period that are neglected by what is called regular history but to which the true painter of an age must draw attention. Behind these respectable fugitives slipped a variety of rogues less closely watched and less suspect. A rogue finding it necessary to disappear could take advantage of the confusion and lose himself among the political refugees; and frequently, as we have just said, would seem in this twilight world, thanks to his greater skill, more respectable than his respectable fellow fugitives. Nothing is more inept than integrity under threat from the law. It is totally at a loss and makes all sorts of mistakes. A forger would find it easier to escape than a member of the Convention.

125

It is a curious thing, but it could almost be said that escape from one's country opened up the possibility of new careers, particularly for dishonest characters. The quantity of civilization that a rascal brought with him from Paris or London was a valuable resource in primitive or barbarous countries; it was a useful qualification and made him an initiator in his new country. It was not by any means impossible for him to exchange the rigors of the law for the priesthood. There is something phantasmagorical in a disappearance, and many an escape has had consequences that could not have been dreamed of. An absconding of this kind could lead to the unknown and the chimerical: thus a bankrupt who had left Europe by some illicit route might reappear twenty years later as grand vizier to the Great Mogul or as a king in Tasmania.

Helping people to escape was a whole industry, and, in view of the numbers involved, a highly profitable one. It could be combined with other kinds of business. Thus those who wanted to escape to England applied to the smugglers, and those who wanted to go to America applied to long-distance operators like Zuela.