The Toilers of the Sea (11 page)

VII

A GHOSTLY TENANT FOR A GHOSTLY HOUSE

Gilliatt was a man of dreams. Hence his acts of daring; hence also his moments of timidity.

He had ideas that were all his own.

Perhaps there was an element of hallucination in Gilliatt, something of the visionary. Hallucinations may haunt a peasant like Martin

83

just as much as a king like Henry IV. The Unknown sometimes holds surprises for the spirit of man. A sudden rent in the veil of darkness will momentarily reveal the invisible and then close up again. Such visions sometimes have a transfiguring effect, turning a camel driver into a Mohammed, a goat girl into a Joan of Arc. Solitude brings out a certain amount of sublime exaltation. It is the smoke from the burning bush. It produces a mysterious vibration of ideas that enlarges the scholar into the seer and the poet into the prophet; it produces Horeb, Kedron, Ombos, the intoxication induced by the chewing of laurel leaves at the Castalian spring, the revelations of the month of Busios,

84

Peleia at Dodona, Phemonoe at Delphi, Trophonius at Lebadeia, Ezekiel by the river Chebar, Jerome in the Thebaid.

Usually the visionary state overwhelms a man and stupefies him. There is such a thing as a divine besottedness. The fakir bears the burden of his vision as the cretin bears his goiter. Luther talking to devils in his garret at Wittenberg, Pascal in his study shutting off the view of hell with a screen, the negro obi conversing with the white-faced god Bossum are all examples of the same phenomenon, diversely affecting the different minds it inhabits according to their strength and their dimensions. Luther and Pascal are, and remain, great; the obi is a poor half-witted creature.

Gilliatt was neither so high nor so low. He was given to thinking a lot: nothing more.

He looked on nature in a rather strange way.

From the fact that he had several times found in the perfectly limpid water of the sea strange creatures of considerable size and varied shape belonging to the jellyfish species that when out of the water resembled soft crystal but when thrown back into the water became one with their natural element, having identical coloring and the same diaphanous quality, so that they were lost to sight, he concluded that since such living transparencies inhabited the water there might be other living transparencies in the air, too. Birds are not inhabitants of the air: they are its amphibians. Gilliatt did not believe that the air was an uninhabited desert. Since the sea is full, he used to say, why should the atmosphere be empty? Air-colored creatures would disappear in daylight and be invisible to us. What proof is there that there are no such creatures? Analogy suggests that the air must have its fish just as the sea has. These fishes of the air would be diaphanousâa provision by a wise Creator that is beneficial both to us and to them; for since light would pass through them, giving them no shadow and no visible form, they would remain unknown to us and we should know nothing about them. Gilliatt imagined that if we could drain the earth of atmosphere, and then fished in the air as we fish in a pond, we should find a multitude of strange creatures. And then, he went on in his reverie, many things would be explained.

Reverie, which is thought in a nebulous state, borders on sleep, which it regards as its frontier area. Air, inhabited by living transparencies, may be seen as the beginning of the unknown; but beyond this lies the vast expanse of the possible.

There

live different creatures;

there

are found different circumstances. There is nothing supernatural about this: it is merely the occult continuation of the infinite natural world. Gilliatt, in the hardworking idleness that was his life, was an odd observer. He went so far as to observe sleep. Sleep is in contact with the possible, which we also call the improbable. The nocturnal world is a world of its own. Night, as night, is a universe. The material human organism, living under the weight of a fifteen-league-high column of air, is tired at the end of the day, it is overcome by lassitude, it lies down, it rests; the eyes of the flesh close; then in this sleeping head, which is less inert than is generally believed, other eyes open; the Unknown appears. The dark things of this unknown world come closer to man, whether because there is a real communication between the two worlds or because the distant recesses of the abyss undergo a visionary enlargement. It seems then that the impalpable living creatures of space come to look at us and are curious about us, the living creatures of earth; a phantom creation ascends or descends to our level and rubs shoulders with us in a dim twilight; in our spectral contemplation a life other than our own, made up of ourselves and of something else, forms and disintegrates; and the sleeperânot wholly aware, not quite unconsciousâcatches a glimpse of these strange forms of animal life, these extraordinary vegetations, these pallid beings, ghastly or smiling, these phantoms, these masks, these faces, these hydras, these confusions, this moonlight without a moon, these dark decompositions of wonder, these growths and shrinkings in a dense obscurity, these floating forms in the shadows, all this mystery that we call dreaming and that in fact is the approach to an invisible reality. The dream world is the aquarium of night.

So, at least, thought Gilliatt.

VIII

THE SEAT OF GILD-HOLM-âUR

Nowadays you will look in vain, in the little bay of Houmet, for Gilliatt's house, his garden, and the creek in which he moored his boat. The Bû de la Rue is no longer there. The little promontory on which it stood has fallen to the picks of the cliff demolishers and has been carried, cartload by cartload, aboard the ships of the rock merchants and the dealers in granite. It is now transformed into quays, churches, and palaces in the capital city. All this ridge of rocks has long since gone off to London.

These lines of rocks extending into the sea, with their fissures and their fretted outlines, are like miniature mountain chains. Looking at them, you have the same kind of impression as would a giant looking at the Cordilleras. In the language of the country they are called banks. They have very different forms. Some are like backbones, with each rock representing a vertebra; others are in the form of herringbones; others again resemble a crocodile in the act of drinking.

At the end of the Bû de la Rue bank was a large rock that the fishing people of Houmet called the Beast's Horn. Pyramidal in shape, it was like a smaller version of the Pinnacle on Jersey. At high tide the sea cut it off from the bank, and it was isolated. At low tide it could be reached on a rocky isthmus. The remarkable feature of this rock, on the seaward side, was a kind of natural seat carved out by the waves and polished by the rain. It was a treacherous place. People were attracted to it by the beauty of the view; they came here “for the sake of the prospect,” as they say on Guernsey, and were tempted to linger, for there is a special charm in wide horizons. The seat was inviting. It formed a kind of recess in the sheer face of the rock, and it was easy to climb up to it: the sea that had hewn it from the rock had also provided a kind of staircase of flat stones leading up to it. The abyss sometimes has these thoughtful ideas; but you will do well to beware of its kindness. The seat tempted people to climb up to it and sit down. It was comfortable, too: the seat was formed of granite worn and rounded by the surf; for the arms there were two crevices in the rock that seemed made for the purpose; and the back consisted of the high vertical wall of the rock, which the occupant of the seat was able to admire above his head, without thinking that it would be impossible to climb. Sitting there, it was all too easy to fall into a reverie. You could look out on the great expanse of sea; you could see in the distance ships arriving and departing; you could follow the course of a sail until it disappeared beyond the Casquets over the curve of the ocean. Visitors were entranced; they enjoyed the beauty of the scene and felt the caress of the wind and the waves. There is a kind of bat at Cayenne that sets out to fan people to sleep in the shade with the gentle beating of its dusky wings. The wind is like this invisible bat: it can batter you, but it can also lull you to sleep. Visitors would come to this rock, look out on the sea and listen to the wind, and then feel the drowsiness of ecstasy coming over them. When your eyes are sated with an excess of beauty and light, it is a pleasure to close them. Then suddenly the visitor would wake up. It was too late. The tide had risen steadily, and the rock was now surrounded by water. He was lost.

The rising sea is a fearful blockading force. The tide swells insensibly at first, then violently. When it reaches the rocks it rages and foams. Swimming is not always possible in the breakers. Fine swimmers had been drowned at the Beast's Horn on the Bû de la Rue.

At certain places and at certain times to look at the sea is a dangerous poison; as is, sometimes, to look at a woman.

The old inhabitants of Guernsey called this recess fashioned from the rock by the waves the Seat of Gild-Holm-âUr or Kidormur. It is said to be a Celtic word, which those who know Celtic do not understand and those who know French do. The local translation of the name is Qui-Dort-Meurt, “he who sleeps dies.” We are free to choose between this translation and the translation given in 1819, I think, in the

Armoricain

by Monsieur Athénas. According to this respectable Celtic scholar Gild-Holm-âUr means “the resting place of flocks of birds.”

There is another seat of the same kind on Alderney, the Monk's Seat, which has been so well fashioned by the waves, with a rock projection so conveniently placed that it could be said that the sea has been kind enough to provide a footstool for the visitor's feet.

At high tide the Seat of Gild-Holm-âUr could no longer be seen: it was entirely covered by water.

Gild-Holm-âUr was a neighbor of the Bû de la Rue. Gilliatt knew it well and used to sit in the seat. He often went there. Was he meditating? No. As we have just said, he did not meditate: he dreamed. He did not allow himself to be caught unawares by the sea.

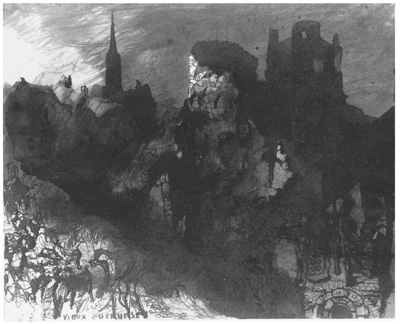

“Vieux Guernesey” (1864â65).

BOOK II

MESS LETHIERRY

I

A RESTLESS LIFE, BUT A QUIET CONSCIENCE

Mess Lethierry, a leading figure in St. Sampson, was a redoubtable sailor. He had sailed far and wide. He had been cabin boy, sail maker, topman, helmsman, leading hand, boatswain, pilot, and master. He was now a shipowner. No man knew the sea as he did. He was intrepid in rescue work. In bad weather he would be out on the shore, scanning the horizon. What's that out there? Someone in trouble? It might be a small fishing-boat from Weymouth, a cutter from Alderney, a bisquine

85

from Courseulle, the yacht of some English lord, an Englishman, a Frenchman, a poor man, a rich man, the Devil himself: it made no difference.

He would jump into a boat and call on two or three stout fellows to join him; but he could do without them if necessaryâcrew the boat all by himself, cast off, take up the oars, and put to sea, sinking into the hollow of the waves and rising to the crest again, plunging into the hurricane, heading for danger. Then he would be seen in the distance amid the gusting winds and the lightning, standing erect in his boat, dripping with rain, like a lion with a mane of foam. Sometimes he spent his whole day in this wayâin danger, amid the waves and the hail and the wind, coming alongside boats in distress, saving their crew, saving their cargo, challenging the storm. Then in the evening he would go home and knit a pair of stockings.

He led this kind of life for fifty years, from the age of ten to sixty, so long as he felt young. Then when he was sixty he noticed that he was no longer able to lift with one hand the anvil in the smithy at Le Varclin, which weighed three hundred pounds; and suddenly he was taken prisoner by rheumatism. He was compelled to give up the sea, and passed from the heroic to the patriarchal age. He was now just a harmless old fellow, rheumaticky and comfortably off. These two products of a man's labor often come together. At the very moment when you become rich you are paralyzed. That rounds off your life. Then men say to themselves: “Let us enjoy life.”

On islands like Guernsey the population consists of men who have spent their life walking around their field and men who have spent their life traveling around the world. There are two kinds of laborers, the workers on the land and the toilers of the sea. Mess Lethierry belonged to the latter category. Yet he also knew the land. He had worked hard all his life. He had traveled on the continent. He had for some time been a ship's carpenter at Rochefort and later at Sète. We have just spoken of sailing around the world. He had made the circuit of France as a journeyman carpenter. He had worked on the pumping machinery of the saltworks in Franche-Comté. This respectable citizen had led the life of an adventurer. In France he had learned to read, to think, to have a will of his own. He had turned his hand to all sorts of things, and in all he had done he had gained a character of probity. At bottom, however, he was a seaman. Water was his element; he would say: “My home is where the fish are.” And indeed his whole life, apart from two or three years, had been devoted to the oceanâas he used to say, he had been “flung into the water.” He had sailed the great seasâ the Atlantic and the Pacificâbut he preferred the Channel. He would exclaim enthusiastically: “That's the real tough one!” He had been born there and wanted to die there. After sailing once or twice around the world he had returned to Guernsey, knowing what was right for him, and had never left it. His voyages now were to Granville and Saint-Malo.

Mess Lethierry was a Guernsey man: that is to say, he was Norman, he was English, he was French. He had within him that quadruple homeland, which was submerged, one might say drowned, in his wider homeland, the ocean. Throughout his life, and wherever he went, he had preserved the habits of a Norman fisherman.

But he also liked to look into a book from time to time; he enjoyed reading; he knew the names of philosophers and poets; and he had a smattering of all the world's languages.

II

A MATTER OF TASTE

Gilliatt was a kind of savage. Mess Lethierry was another. But this savage had some refined tastes.

He was particular about women's hands. In his early years, while still a lad, somewhere between seaman and cabin boy, he had heard the Bailli de Suffren

86

say: “There goes a pretty girl, but what horrible great red hands!” A remark by an admiral, on any subject, carries great weight: it is more than an oracle, it is an order. The Bailli de Suffren's exclamation had made Lethierry fastidious and exacting in the matter of small white hands. His own hand was a huge mahogany-colored slab; a light touch from it was like a blow from a club, a caress was like being grasped by pincers, and a blow from his clenched fist could crack a paving stone.

He had never married. Either he did not want to get married or he had never found the right woman. It may have been because he wanted someone with the hands of a duchess. There are few such hands to be found among the fisher girls of Portbail.

87

It was rumored, however, that once upon a time, at Rochefort in the Charente, he had found a grisette who matched up to his ideal. She was a pretty girl with pretty hands. She had a sharp tongue, and she scratched. Woe betide anyone who attacked her! Her nails, exquisitely clean, without reproach and without fear, could on occasion become claws. These charming nails had enchanted Lethierry and then had begun to worry him; and, fearing that one day he might not be the master of his mistress, he had decided against appearing before the mayor with this particular bride.

Another time he was attracted by a girl on Alderney. He was thinking of marriage when an Alderney man said to him, “Congratulations! You will have a good dung-woman for a wife.” He had to have the meaning of this commendation explained to him. It referred to a practice they have on Alderney. They collect cowpats and throw them against a wall; there is a particular way of throwing them. When they are dry they fall off the wall. The cakes of dried dung, known as

coipiaux,

are then used for heating the house. An Alderney girl will get a husband only if she is a good dung-woman. Lethierry was scared off by this talent.

In matters of love and lovemaking he had a good rough-and-ready peasant philosophy, the wisdom of a sailor who was always being captivated but was never caught, and he boasted of having been easily conquered in his younger days by a “petticoat.” What is now known as a crinoline was then called a petticoatâmeaning something more and something less than a woman.

These rude seafaring men of the Norman archipelago have a certain native wit. Almost all of them can read and do read. On Sundays you can see little eight-year-old cabin boys sitting on a coil of rope with a book in their hands. These Norman seamen have always had a sardonic turn of mind and are ever ready with an apt remark, what we nowadays call a

mot.

It was one such man, a daring pilot called Quéripel, who addressed Montgomery, who had sought refuge on Jersey after accidentally killing King Henry II in a tournament, with these words: “An empty head broken by a foolish one.” Anotherâ Touzeau, a sea captain of St. Breladeâwas the author of the philosophical pun wrongly attributed to Bishop Camus:

Après la mort les

papes deviennent papillons et les sires deviennent cirons

(“After death popes become butterflies and seigneurs become mites”).

III

THE OLD LANGUAGE OF THE SEA

These seamen of the Channel Islands are true old Gauls. The islands, which are now rapidly becoming anglicized, long remained independent. Countryfolk on Sark speak the language of Louis XIV.

Forty years ago the classical language of the sea could be heard in the mouths of the seamen of Jersey and Alderney. A visitor would have found himself carried back to the seafaring world of the seventeenth century. A specialist archaeologist could have gone there to study the ancient language, used in working ships and in battle, roared out by Jean Bart

88

through the loud-hailer that terrified Admiral Hyde. The seafaring vocabulary of our fathers, almost completely changed in our day, was still in use on Guernsey around 1820. A ship that was a good plyer was a

bon boulinier,

one that carried a weather helm, in spite of her foresails and rudder, was a

vaisseau ardent.

To get under way was

prendre l'aire;

to lie to in a storm was

capeyer;

to make fast running rigging was

faire dormant;

to get to windward was

faire chapelle;

to keep the cable tight was

faire teste;

to be out of trim was

être en pantenne;

to keep the sails full was

porter plain.

All these terms have fallen out of use. Today we say

louvoyer

(to beat to windward), they said

leauvoyer;

for

naviguer

(to sail) they said

naviger;

for

virer

(to tack) they said

donner vent devant;

for

aller de l'avant

(to make headway) they said

tailler de l'avant;

for

tirez d'accord

(haul together) they said

halez d'accord;

for

dérapez

(weigh anchor),

déplantez;

for

embraquez

(haul tight),

abraquez;

for

taquets

(cleats),

bittons;

for

burins

(toggles),

tappes;

for

balancines

(lifts),

valancines;

for

tribord

(starboard),

stribord;

for

les hommes de quart à bâbord

(men of the port watch), les basbourdis. Admiral Tourville

89

wrote to Hocquincourt, Nous

avons singlé

(sailed) instead of

cinglé.

They said

le ra fal

for

la rafale

(squall);

boussoir

for

bossoir

(cathead);

drousse

for

drosse

(truss);

faire une

olofée

for

lo fer

(to luff );

alonger

for

élonger

(to lay alongside);

survent

for

forte brise

(stiff breeze);

jas

for

jouail

(stock of an anchor);

fosse

for

soute

(storeroom).

Such, at the beginning of this century, was the seafarers' language of the Channel Islands. If he had heard a Jersey pilot speaking, Ango

90

would have been puzzled. While everywhere else sails

faseyaient

(shivered), in the Channel Islands they

barbeyaient.

A

saute de vent

(sudden shift of wind) was a

folle-vente.

Only there were the two antique methods of mooring,

la valture

and

la portugaise,

still in use. Only there could be heard the old commands

tour et choque!

and

bosse et bitte!

While a seaman of Granville was already using the term

clan

for sheave hole, a seaman of St. Aubin or St. Sampson was still saying

canal de pouliot.

The

bout d'alonge

(upper futtock) of Saint-Malo was the

oreille d'âne

of St. Helier. Mess Lethierry, just like the duc de Vivonne,

91

called the sheer of a deck the

tonture

and the caulker's chisel a

patarasse.

It was with this peculiar idiom in their mouths that Duquesne beat Ruyter, Duguay-Trouin

92

beat Wasnaer, and Tourville, in broad daylight, put down anchors fore and aft on the first galley that bombarded Algiers in 1681. It is now a dead language. Nowadays the jargon of the sea is quite different. Duperré

93

would not understand Suffren.

The language of naval signals is likewise transformed. We have moved on a long way from the four pennantsâred, white, blue, and yellowâof La Bourdonnais

94

to the eighteen flags of today, which, hoisted in twos, threes, or fours, facilitate communication at a distance with their seventy thousand combinations, are never at a loss, and, as it were, foresee the unforeseen.

IV

YOU ARE VULNERABLE IN WHAT YOU LOVE

Mess Lethierry wore his heart on his hand: a big hand and a big heart. His failing was that admirable quality, confidence in his fellowmen. He had a very personal way of undertaking to do something: with an air of solemnity, he would say: “I give my word of honor to God,” and would then go ahead and do what he had undertaken. He believed in God, but not in any of the rest. He rarely went to church, and when he did it was merely out of politeness. At sea he was superstitious.

Yet he had never been daunted by any storm. This was because he was intolerant of opposition. He would not put up with it from the ocean any more than from anyone else. He was determined to be obeyed. So much the worse for the sea if it resisted his authority: it would just have to accept the fact. Mess Lethierry would not give way. He would no more be stopped by a rearing wave than by a quarrelsome neighbor. What he said was said; what he planned to do was done. He would not bend before an objection nor before a storm at sea. For him the word

no

did not exist, either in the mouth of a man or the rumbling of a thundercloud. He pressed on regardless. He would take no refusals. Hence his obstinacy in life and his intrepidity on the ocean.

He liked to season his own fish soup, knowing the exact measure of pepper and salt and herbs required, and took pleasure in making it as well as in eating it. A man who is transfigured by oilskins and demeaned by a frock coat; who, with his hair blowing in the wind, looks like Jean Bart, and, wearing a round hat, like a simpleton; awkward in town, strange and redoubtable at sea; the broad back of a porter, never an oath, seldom angry, a gentle voice that turns to thunder in a loud-hailer, a peasant who has read the

Encyclopédie,

a Guernsey man who has seen the Revolution, a learned ignoramus, with no bigotry but all kinds of visions, more faith in the White Lady than in the Virgin Mary, the strength of Polyphemus, the will of Columbus, the logic of the weather vane, with something of a bull and something of a child about him; almost snub-nosed, powerful cheeks, a mouth that has preserved all its teeth, a deeply marked face, buffeted by the waves and lashed by the winds for forty years, a brow like a brooding storm, the complexion of a rock in the open sea; then add to this rugged face a kindly glance, and you have Mess Lethierry.

Mess Lethierry had two special objects of affection: Durande and Déruchette.