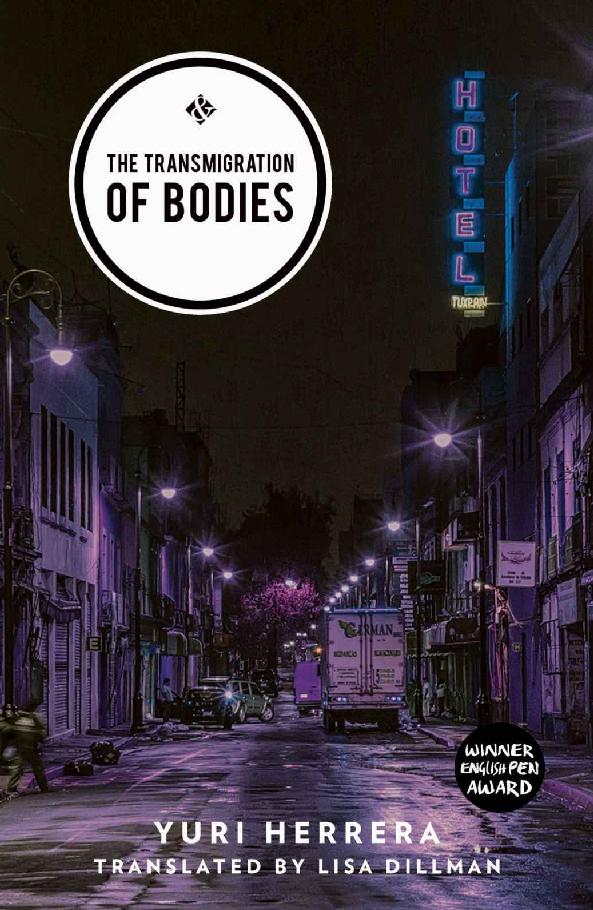

The Transmigration of Bodies

Read The Transmigration of Bodies Online

Authors: Yuri Herrera

Tags: #Vicky, #Three Times Blond, #Romeo, #blonde, #translated fiction, #Neyanderthal, #the Dolphin, #Anemic Student, #Hard-Boiled, #valeria luiselli, #yuri herrera, #Urban, #mexico city, #plague, #The Redeemer, #Trabajos del Reino, #daniel alarcón, #Spanish, #mediation, #narco-literature, #gang violence, #mexico, #la Nora, #francisco goldman, #herrera, #signs preceding the end of the world, #La transmigración de los cuerpos, #redeemer, #the Unruly, #the Castros, #The Transmigration of Bodies, #narcoliteratura, #love story, #Novel, #Hispanic, #Translation, #maya jaggi, #disease, #drama, #Ganglands, #latino, #dead bodies, #Transmigration of the Bodies, #Fiction, #gangs, #dystopia, #Señales que precederán al fin del mundo

PRAISE FOR

The transmigration of bodies

“Yuri Herrera’s novels are like little lights in a vast darkness. I want to see whatever he shows me.”

Stephen Sparks, Green Apple Books, San Francisco, CA.

“This is as noir should be, written with all the grit and grime of hard-boiled crime and all the literary merit we’re beginning to expect from Herrera. Before the end he’ll have you asking how, in the shadow of anonymity, do you differentiate between the guilty and the innocent?”

Tom Harris, Mr B’s Emporium, Bath.

“Both hysterical and bleak,

The Transmigration of Bodies

builds an entire world in 100 pages. Herrera’s ability to express everything in so few words, his skill of merging the argot of the streets with the poetry of life is unrivaled. The world his characters inhabit is dangerous and urban, like a postcard sent from the ends of the earth. Reading his compact novels is both exhilarating and unforgettable.”

Mark Haber, Brazos Bookstore, Houston, TX.

“A fabulous book full of low-life characters struggling to get by. It’s an everyday story of love, lust, disease and death. Indispensible.”

Matthew Geden, Waterstones Cork, Ireland.

“Reading

The Transmigration of Bodies

was akin to being enveloped in a dream state, yet one that upon waking somehow makes profound sense. Another truly magnificent novel from one of the most exciting authors to emerge on the world stage for aeons.”

Ray Mattinson, Blackwell’s, Oxford.

“A microcosmic look at the lives of two families straight out of a Shakespearean drama. Pick it up and you won’t put it down till you’ve finished.”

Grace Waltemyer, Posman Books in Chelsea Market, NY.

“A work replete with the gritty, informal prose first displayed in

Signs

—rooted firmly in the modern world yet evoking the feel of an epic divorced from time… a cross between Cormac McCarthy and a detective novel, an incisive portrait evoking a Mexican

Inherent Vice

.”

Marina Clementi, Seminary Co-op Bookstore, Chicago, IL.

“

The Transmigration of Bodies

reads like a fever dream: an intense, enthralling examination of how people live in a city of the dying and the dead. It takes an extraordinary amount of skill to combine elements of noir, political commentary, hardboiled crime, and allegory (not to mention Shakespeare, with a seasoning of existential ennui) and keep the novel moving, or in this case, racing along. Herrera, clearly, has at least that much talent, and then some.”

Thomas Flynn, Volumes Bookcafe, Chicago, IL.

First published in English translation in 2016 by

And Other Stories

High Wycombe – Los Angeles

www.andotherstories.org

Copyright © Yuri Herrera, 2013

First published as

La Transmigración de los cuerpos

in 2013 by Editorial Periférica, Madrid, Spain

English-language translation copyright © Lisa Dillman 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transported in any form by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher of this book.

The right of Yuri Herrera to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or places is entirely coincidental.

ISBN 9781908276728

eBook ISBN 9781908276735

Editor: Tara Tobler; typesetting and eBook:

Tetragon, London

; cover design: Hannah Naughton; cover image (modified): iivangm

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book has been selected to receive financial assistance from English PEN’s PEN Translates! programme. English PEN exists to promote literature and our understanding of it, to uphold writers’ freedoms around the world, to campaign against the persecution and imprisonment of writers for stating their views, and to promote the friendly co-operation of writers and the free exchange of ideas.

www.englishpen.org

This book also was supported using public funding by Arts Council England.

For my mother, Irma Eugenia Gutiérrez Mejía

1

A scurvy thirst awoke him and he got up to get a glass of water, but the tap was dry and all that trickled out was a thin stream of dank air. Eyeing the third of mezcal on the table with venom, he got the feeling it was going to be an awful day. He had no way of knowing it already was, had been for hours, truly awful, much more awful than the private little inferno he’d built himself on booze. He decided to go out. He opened his door, was disconcerted not to see the scamper of la Ñora, who’d lived there since the days when the Big House was actually a Big House and not two floors of little houses—rooms for folks half-down on their luck—and then opened the front door and walked out. The second he took a step his back cricked to tell him something was off.

He knew he wasn’t dreaming because his dreams were so unremarkable. If ever he managed to sleep several hours in a row, he dreamed, but his dreams were so lifelike they provided no rest: only small variations on his everyday undertakings and his everyday conversations and everyday fears. Occasionally his teeth fell out, but aside from that it was just everyday stuff. Nothing like this.

Buzzing: then a dense block of mosquitos tethering themselves to a puddle of water as tho attempting to lift it. There was no one, nothing, not a single voice, not one sound on an avenue that by that time should have been rammed with cars. Then he looked closer: the puddle began at the foot of a tree, like someone had leaned up against it to vomit. And what the mosquitos were sucking up wasn’t water but blood.

And there was no wind. Afternoons it blew like a bitch so there should’ve at least been a light breeze, yet all he got was stagnation. Solid lethargy. Things felt much more present when they looked so abandoned.

He closed the door and stood there for a second not knowing what to do. He returned to his room and he stood there too, staring at the table and the bed. He sat on the bed. What worried him most was not knowing what to fear; he was used to fending off the unexpected, but even the unexpected had its limits; you could trust that when you opened the door every morning the world wouldn’t be emptied of people. This, tho, was like falling asleep in an elevator and waking up with the doors open on a floor you never knew existed.

One thing at a time, he said to himself. First water. Then we’ll figure out what the fuck. Water. He pricked up his nose and turned, attentive, to look around the place again and then said aloud Of course. He got up, went into the bathroom with a glass, pulled the lid off the tank and saw barely three fingers; he’d gotten up in the night to piss and the tank hadn’t refilled after he flushed. He scraped the bottom with the glass but there was only enough for half. One drop of water was all that was left in his body and it had picked a precise place on his temple to bore its way out.

Fuckit, he said. Since when do I believe those bastards?

Four days ago their song and dance seemed like a hoax. Like the shock you feel when someone jumps out at you from behind a door and then says Relax, it’s only me. Everyone was sure: if it was anything at all, it was no big shit. The disease came from a bug and the bug only hung around in squalid areas. You could swat the problem against the wall with a newspaper. Those too broke for a paper could use a shoe: no need to give them every little thing, after all. And

Too poor for shoes!

became the thing you spat at people who sneezed, coughed, swooned, or moaned

O

.

Only the ground floor of the Big House was actually inhabited, and of the inhabitants only the anemic student had actually been afraid. Once the warnings started he could be heard running to his door to spy through the peephole when anyone went in or out of the building. La Ñora certainly kept going out, keeping tabs on everyone on the block. And he’d seen Three Times Blonde go out one morning with her boyfriend. It unhinged him, having her so close, Three Times Blonde sleeping and waking and bathing only a wall and tiles away, Three Times Blonde pouring herself into itty-bitty sizes, her pantyline smiling at him as she walked off. She never noticed him at all, not even if they were leaving at the same time and he said Excuse me or You first or Please, except on one occasion when she was with her boyfriend and for a moment she’d not only turned to look at him but even smiled.

What did he expect, a man like him, who ruined suits the moment he put them on: no matter how nice they looked in shop windows, hanging off his bones they wrinkled in an instant, fell down, lost their grace. Ruined by the fetid stench of the courthouse. Or else his belongings just realized that his life was like a bus stop, useful for a moment but a place no one would stay for good. And she went for boyfriends like the one he’d seen—some slicked-back baby jack, four shirt buttons undone so everyone could see his gold virgin. The boyfriend had said hello, tho. Like the guy at the bar who tips on arrival so his drinks get poured with a heavy hand.

For the past four days the message had been Stay calm, everybody calm, this is not a big deal. On a bus, he himself had witnessed the pseudo-calm of skepticism: a street peddler had boarded the bus selling bottles of bubble gel; he blew into a plastic ring and little solar systems sailed down the aisle, oscillating, suspended, landing on people without bursting. Gel bubbles, he said, last far longer than soap bubbles, you can play with them, and he took a few between his fingers, jiggled, pressed, and puffed. One popped on a man’s forehead. And just then the penny dropped: the bubble was full of air and spit from a stranger’s mouth. A rictus of icy panic spread across the passengers’ faces; the man got up and said Get the fuck off, the peddler stammered What’s the problem, friend, no need to act like that, but the guy was already on him. When the guy lifted him up by his sweater the driver slowed—just a bit—and opened the doors so the vendor and his bottles could be tossed to the curb. Then he closed the doors and sped back up. And no one said a word. Not even him.

But at the time, they could still think they’d escaped the danger. Last night’s news was no longer a dodge. The story had been picked up everywhere: two men in a restaurant, total strangers, started spitting blood almost simultaneously and collapsed over their tables. That was when the government came out and admitted:

We believe the epidemic

—and that was the first time they used the word—

may be a tad more aggressive than we’d initially thought, we believe it can only be transmitted by mosquitos

—

EGYPTIAN

mosquitos, they underscored—

tho there have been a couple of cases that appear to have been spread by other means, so while we are ruling out whatever we can rule out it’s best to stop everything, tho really there’s no cause for concern, we have the best and brightest tracking down whatever this is, and of course we have hospitals, too, but, just in case, you know, best to stay home and not kiss anybody or touch anybody and to cover your nose and your mouth and report any symptoms, but the main thing is Stay Calm

. Which, logically, was taken to mean Lock yourself up or this fucker will take you down, because we’ve unleashed some serious wrath.

He opened the Big House door again, took two steps out and was thrust back by the reek of abandonment on the street. Almost imperceptibly his frame flexed, anxious, updown updown, Fuckit fuckit fuckit, what do I do, and then he felt something brush his neck and he slapped his skin and looked at his hand, stained with insect blood. He stepped back, slammed the door and stood staring at his palm, transfixed.

What’s going on? he heard behind him. He turned to see Three Times Blonde at the end of the hall. Half her body hanging out of her apartment, swinging from the jamb with one hand.

He took two steps toward her, wiping his hand on his pants.

What’s that? she asked.

Grease.

Three Times Blonde relaxed a bit and asked again.

What’s going on out there?

Nothing, he replied. And I mean not a thing.

She nodded. She’d probably been watching the news without daring to believe it.

Good morning, he said.

Afternoon, you mean, Three Times Blonde fired back. She blinked silently at the ground, an outburst held in, and then added I got no credit on my phone.

Take some of mine, he offered immediately, as tho gravity itself forced him to say such things in the presence of a woman.

Three Times Blonde stood aside, and tho they could have done the deal in the hall she ticked her head toward her place. Her apartment gloried in its own good taste: purple love seat, poster of a blonde on an armchair not unlike the love seat, blue rug. He asked if he

might

possibly

have a glass of water, thinking she was the sort who put stock in proper talk, but she just shot him a strange look.

They trafficked his time and she turned her back to make her call.

Three Times Blonde’s pants rode her all over. He ogled her like she was in a window display, seized by the urge to devour her, to gorge himself on her thighs and her back and her tongue and then ask for her bones in a little bag to go. He pulled her blue pants down slow and trembling—but no, he didn’t lift a finger; he inhaled the nape of her neck and kissed the three-times-blonde hair on it—but no, his hands stayed folded before him like the tea-sipping innocent he knew he could pass for. She was on the phone saying So what’s going to happen, are we going to die or what? Then why won’t you come over? But you have a car, you don’t have to see a soul… Oh. And there’s nobody that can stay with them? Whatever. Well if you don’t come now it’s going to get worse and then you really will be stuck there forever with your mother and your sisters, yeah, yeah, I know, it’ll all be over soon, fine, okay, yeah, love you too, kiss-kiss.

She turned back around. He’s not coming.

He should have taken off right then, should have said You’re welcome—tho she hadn’t said thanks—and split. But his will wasn’t his own.

Let’s watch TV, she said, and went into her bedroom.

He approached, not daring to cross the threshold. The room was pink and pillowed. She sat on the edge of the bed and turned on the TV and patted the mattress. Come.

Suddenly he began to salivate, his mouth no longer a desert with buzzards circling his tongue but a choking street, a flooded sewer. He obeyed and instructed himself to move no further. The newscaster on TV was talking about the airborne monster, its body a shiny striped black bullet, six very long fuzzy legs humped over itself, and above the hump a little round head with antennae casting out into space and two tubular mouths. A bona fide sonofabitch, apparently.

Looks pretty determined, don’t you think? she asked.

He nodded yes and swallowed spit, then said But who knows if that’s even the one, maybe they just found a fall guy, maybe this bug’s taking the rap for another bug’s dirtywork.

It was a joke, but Three Times Blonde turned to him wide-eyed and said You are so right it’s scary.

She was convinced. Maybe it was true, maybe he was right.

Then the power went out. Three Times Blonde’s apartment, just like his, got no natural light since they were at the back of the Big House, so suddenly it was dead of night. She said Yikes! and then fell silent, they both fell silent, a sensual silence, surreptitious: no need to do a thing. No need for phony swagger and no need to shoot her sidelong glances as if the door were half-open, just sit tight, knowing she’s within kissing distance, even if no one else knows it and even if you can’t prove it, it’s a leap of faith.

So that was what it felt like: not always thinking about the moment to come, wasting each moment thinking about the moment to come, always the coming moment. So that was what it felt like to incubate, to settle in with yourself and hope the light stays off. And astonishingly, like a miracle, she said: I think this is what we were like before we were babies, don’t you? Little larvae, sitting quietly in the dark.

He said nothing. Her voice had brought him back to the mattress, there in her pillowed room. Again he wanted to touch her and again he lacked someone to loan him the will.

You want a drink?

Oooh, yeah, I could go for a vodka.

I got mezcal.

He pictured her twisting her lips.

Well. You got to try everything once, right?

They got up off the bed and she placed one hand on his arm and one on his back.

Don’t fall. If you conk out I won’t be able to pick you up. He let himself be led slower than necessary so she’d have to keep holding on. She opened the door and a square of light appeared from the small window in the door at the end of the hall.

Be right back.

He made it to the table in his apartment without fumbling, snatched up the bottle, and, with the skill of someone who’s come home sloshed more than once, located the shot glasses. Before going back he walked to the end of the hall and looked out. He saw that the mosquitos had abandoned their puddle and what he’d thought was blood was in fact black floating scum. He recalled that on previous days he’d spotted several puddles covered in whitish membranes. This was the first black one he’d seen.

The city was still silent, overtaken by sinister insects.

On his way back he guided himself by the little inferno of her oven. The backlit blue silhouette of Three Times Blonde could be seen as she cut cheese, tomato and chipotle.

We’re going to have something to eat, so I don’t get silly when I drink.

They flipped and double-flipped and then folded the tortillas. Ate standing up. Then began to drink.

So how come nobody ever comes to visit you? she asked.

Everyone’s fine right where they are, he replied. And me and mezcal don’t talk shop.

Lonely people lose their minds, she said.

He always found it a miracle that anyone wanted his company. Women especially—men will cuddle a rock. When he first started getting laid he couldn’t quite believe that the women in his bed weren’t there by mistake. Sometimes he’d leave the room and then peer back in, and then peer in again, incredulous that a woman was actually lying there naked, waiting for him. As if. In time he found his thing: fly in like a fool to start, then turn on the silver tongue. Talk and cock, talk and cock, yessir. One time a girl confessed that Vicky, his friend the nurse, had given her a warning before she introduced them. Take one look and if you don’t like what you see don’t even say hi or you’ll end up wanting to fuck. Best thing anyone ever said about him. It didn’t matter that they never came back, or rarely. He didn’t mind being disposable.