The Two of Us (18 page)

Authors: Sheila Hancock

On the whole, John tried his best not to disappoint his fans. On one occasion he played a whole charity football match with

a broken arm rather than let Regan be stretchered off. He fended off female embraces as politely as possible. When approached

in a supermarket he was known to say to autograph hunters, ‘Sorry, no,’ and if they persisted he would snap, ‘Fuck off.’ If

I remonstrated with him, pointing out that he was dependent on the public so should at least be polite, he would explain his

reluctance: ‘I don’t want to have to be Mr Nice Guy all the time. I do my job, now leave me alone.’ Eventually he stopped

going to public places unless he had to.

25 February

Rushed cremation to avoid the press. Sad little nothing ceremony.

Strauss’s last song sung by his beloved Schwarzkopf,

a bit of the Elgar Cello Concerto, some Charlie Parker and

silence. Flowers and leaves from the garden to put on his

coffin. Just the family. No priest, no palaver. We will do

more later. Then home to lunch with the people who work

at the house. Suddenly desperate to be alone so I asked the

family to go back to London and leave me. When they’d

gone, I howled like an animal, prowling round, looking for

traces of him. I can still smell him but he has absolutely

gone. Utter despair at his absence, his total absence. I feel

as though a whole part of me has been hacked away, leaving

a bleeding gaping wound. I sit, lie on the floor, crouch,

trying to stop the physical pain of it. I weep and weep and

weep. I can’t do anything without him. Watch TV, have a

cup of tea, cook, it is all linked with him. I’m talking to

him as if he were there, but he’s not, he’s so not.

The children could not hide away. Joanna was too young to be riled at being called the Teeny Sweeney, but Abigail and Ellie

Jane found the limelight disconcerting. They were not allowed to watch the show as it was too late and, I thought, too violent

for nine- and ten-year-olds. It could be disturbing to see your dad beating people to a pulp, not to mention hopping into

bed with nubile women who were definitely not their mum. This put them at a disadvantage when kids in the playground discussed

the finer points of last night’s punch-up or hummed the theme tune at them in the corridors. Harry South’s music contributed

hugely to the success of the show as, later, did Barrington Phelong’s

Morse

theme. It was a show everyone talked about next morning in the bus queue and, whilst giving the girls street cred, it was

confusing to equate the man slaving over the Sunday roast with the title of Thinking Woman’s Crumpet. Unusually for such a

popular show it was a critical success; more importantly to John, it was admired by his peers. John was the first to win the

highly esteemed BAFTA Best Actor award, normally reserved for weighty drama and venerable actors, for a prime-time series.

The awards mounted up for the programme and John. It was a mixed blessing. He was honoured but his sweaty hand would cling

to mine as we walked up the red carpet between baying photographers and fans. The brevity of his terrified acceptance speeches

was welcomed in the endless evenings, if sometimes appearing a little graceless. The most enjoyable accolade Dennis and John

received was to be invited on to the

Morecambe and

Wise Christmas Show

. In return they persuaded the two comics to appear in an episode of

The Sweeney

. A great deal of liquor was imbibed, before, after and during the filming. The script was peppered with inspired ad-libs

from Eric, and Ted Childs had difficulty in bringing them to order. He frequently arrived on set to find everyone ‘rolling

about laughing with their legs in the air, having a lovely party but not doing a lot of work’. When eventually John reeled

home he would recount Eric’s latest

bons mots

with glee, and the more he fell about with laughter, the less I was amused.

Stuck at home with a small baby and a difficult ten-year-old, I was having nowhere near as much fun. In addition, having just

finished converting one new home, John had heard that a Victorian Gothic house at the end of the road, with a garden backing

on to the river, was up for sale. He insisted on a visit. We were shown round by an old lady who had lived there for years

without doing anything to the house. There was no heating, gas lighting, and the kitchen was a cracked sink and rusty cooker

in the basement. Original features, they called them. But there were also stained-glass windows, marble fireplaces and a Victorian

summerhouse with the Thames lapping at its windows. John leaned against the stone wall at the bottom of the garden, the river

behind him, and uttered quietly the phrase I came to dread: ‘I wan’ it.’ By this time Mrs Fitzwalter was enchanted by John’s

passion for the house, which extended to mowing the overgrown lawn for her. She rejected all the rich Arabs and pop stars

fighting for it and was prepared to wait till we had raised the asking price, which she lowered for us. So, once more, I was

plunged into the nightmare of builders not turning up and then going bankrupt, exquisite original tiled floors collapsing

with dry rot, and cats being trapped under floorboards. Despite our odd childhoods, both of us had grown up with the belief,

still prevalent in the seventies, that a woman’s place really is in the home and the man is the official hunter-gatherer.

Trouble was, I too was hunting and gathering as well as earth-mothering, and I’d read

The Female Eunuch

.

Then there was the jealousy. While I was cow-like feeding my baby, at work he was leaping between the sheets with lithe beauties

with no stretch marks. I could not believe they did not lust after him as I did. John, for his part, was shocked that I should

doubt the loyalty of a man who doesn’t play games.

As I was working at night in a theatre play and John during the day on television, we saw little of each other. John was working

a sixteen-hour day so he was exhausted. In three short years he had gone from being a bachelor, seeing his one child at weekends,

doing the odd bit of telly, to becoming a husband and father with two homes, three children and worldwide renown. It was no

wonder that he needed a few drinks to help him on the way. Just like my father and Alec. Aware that the drinks had become

more than a few, on my advice he decided to go to a health farm to recuperate, starting with a fast. There he obviously ruminated

on my moans: ‘Just a little note to tell you I feel very weak and can’t get it together, I have a terrible headache and I

love you very much. I was talking to Roy [a masseur] about your

This Is Your Life

and felt very proud to be part of that life. I’m very proud of the love you give me, the trouble you go through for me, and

proud of the children you gave me. In short you are the most beautiful woman – person – in the world, kid. Help me, help me,

mangé, mangé.’ I liked the pc use of ‘person’.

26 February

Woke up after a few hours’ sleep and realised it was still

true. Girls phoned to say they are coming to get me, but

I am not fit to face anyone. Thousands of letters. I know

these people are actually hurting, but oh God what I’m

feeling is beyond comfort. Nothing helps. Especially that

‘Death is nothing at all’ bollocks. Oh really? And no, he

isn’t in the sodding next room. The thoughtful strangers

say it will help me but it makes me roar with rage. OK,

you say I’ll meet him again. Prove it. I would like to believe

it, God would I like to. If I thought it was true I’d kill

myself and meet him now. I have absolutely no sense of

his presence. He is utterly gone and I can’t bear it.

One aspect of his success John relished was the increased wealth it brought. His childhood had given him a dread of poverty.

Yet for both of us there was ambivalence in our attitude to our newfound affluence; relish tinged with guilt. But John needed

tangible proof of his success – a big motor, a big house. He loved giving presents. He showered me with jewellery and the

kids with toys. I only had to admire something and he would say, ‘You wan’ it, kid?’, be it a saucepan, a Picasso in the Tate

or the Eiffel Tower. It was a way of demonstrating his love and he lapped up our pleasure. He was bad at receiving presents,

often not undoing his Christmas gifts from one year to the next. It was as though he felt unworthy of them. The one thing

he bought for himself was radios. He could never resist a new model. Especially for the bathroom. If he turned on the radio

loud enough, he could stay there for ages, not hearing our calls. If he did, his reply was, ‘Ahm in ze bas’ and we would know

we’d lost him for another hour.

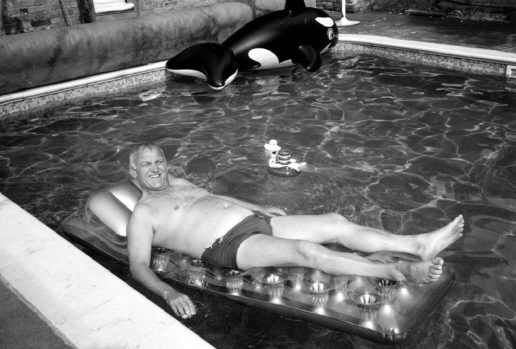

We splashed out on a swimming pool, which gave him endless pleasure. Not to swim in. He rarely ventured into the water and,

when he did, the shuddering and howling were heard throughout Chiswick. His chief joy was cleaning it. He had a mechanical

cleaner that he christened Fred. He passed many a happy morning chuckling as it scurried round the bottom of the pool, cracking

its plastic tail. Jo refused to go into the pool for several days after he warned her that it ate little girls. Other than

that, he would scoop off the leaves with a net and then clamber clumsily on to a big plastic lilo on which he would float

blissfully, imbibing a large one sitting on a lilo of its own. ‘Oh yes, this is ze life, I tell you.’

Our luck was not shared by the rest of the country. The miners and teachers were building up to major strikes and people were

being made redundant as unemployment rose. Heath had gone to the country hoping for a vote of confidence on his ‘Who Rules

Britain’ ticket, only to be defeated by Wilson whose comment on victory was, ‘All I can say is my prayers.’ The atmosphere

was not helped by a series of horrific murders carried out by a mysterious Yorkshire Ripper. It seemed a good time to go abroad.

John’s brother Ray was feeling homesick in Brisbane, so when we were offered a tour of Michael Frayn’s play

The Two of Us

in Australia, it was an opportunity to take the whole family on a visit. The first night in Melbourne could not be counted

as a triumph. The last act of the piece required us to play many parts, changing costume in the wings and rushing on miraculously

transformed. It was meant to be funny, but was not to the rather stuffy people of Melbourne, which in architecture and atmosphere

felt like Cheltenham. There was scarcely a titter. One of the last lines commenting on the party we were depicting was, ‘I

think that went well, don’t you?’ Sweating and wilting, John collapsed into giggles, I followed suit and the curtain descended

in confusion. We decided it was not wise for The Two of Us to work together.

Our journey home too had its down side. We took Ellie Jane with us to Bali, and then India. Bali in the seventies was not

such a popular tourist destination as it is now. Our trip was organised by that great traveller, Derek Nimmo, and we were

staying with a Balinese antique dealer, Jimmy Pandi. We dined under the stars, swam in the warm sea and visited remote villages

full of beautiful people. So unused were they to foreigners that they crowded round us, particularly fascinated by blonde,

blue-eyed Ellie Jane. There were dark tales of purges of Communists and corruption in high places, but it seemed a blissfully

happy place. By contrast, the poverty we saw in India made it impossible for us really to enjoy its magnificence. The Taj

Mahal is beautiful beyond expectation, seeming to float on air, but we found it difficult to see through the beggars. One

day when I was entering into the spirit of the place and bartering with a merchant over the price of a bracelet, John leaned

on the stall and wailed, ‘Oh, I can’t wait to see Doris at the Express Dairy.’ He shut himself in the hotel and ordered a

bottle of vodka and a bottle of whisky. So amazed were they at this lavish order of exorbitantly priced drinks that it arrived

with thirty glasses and a bowl of peanuts. John hid away in the hotel with his booze and refused to go out any more. Ellie

and I braved the huge bats and rabid dogs of Udaipur alone. It is a philistine reaction to an obviously fascinating country,

but we were riddled with guilt to be flashing cameras and other signs of wealth about whilst others needed to beg to eat.

27 February

Propped up my face with make-up and took four-year-old

Lola as protection to face the world in Marks and Spencer.

People kept clutching my hand and saying kind things. I

bit the sides of my mouth to stop crying. Lola was strangely

silent, sitting on my trolley. She listened to all these

comments and looked at me struggling and suddenly in a

sing-song voice with a sort of mock-Jewish shrug she said

at the checkout, ‘Now look, Grandad’s dead, he won’t come

back, but you’re very old so you’ll be dead soon too.’ It

was obviously a garbled version of Ellie’s attempt to explain

things to her. It was the first time I’ve laughed, so of course

she went on and on: ‘Grandad won’t want that coffee

because he’s dead,’ ‘Grandad likes cream cake but he won’t

want them now because he’s gone for ever.’ At least she’s

coming to terms with it.