The unbearable lightness of being (5 page)

Read The unbearable lightness of being Online

Authors: Milan Kundera

32

he

did not. From the Swiss doctor's point of view Tereza's move could only appear

hysterical and abhorrent. And Tomas refused to allow anyone an opportunity to

think ill of her. The director of the hospital was in fact offended. Tomas

shrugged his shoulders and said,

"Es muss sein. Es muss sein."

It

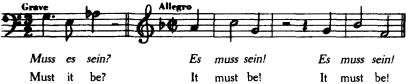

was an allusion. The last movement of Beethoven's last quartet is based on the

following two motifs:

To make the meaning of the words absolutely clear, Beethoven introduced

the movement with a phrase,

"Der schwer gefasste Entschluss,"

which is commonly translated as "the difficult resolution."

This allusion to Beethoven was actually Tomas's first step back to Tereza,

because she was the one who had induced him to buy records of the Beethoven

quartets and sonatas.

The allusion was even more pertinent than he had thought because the

Swiss doctor was a great music lover. Smiling serenely, he asked, in the

melody of Beethoven's motif,

"Muss es sein?"

"]a,

es muss sein!"

Tomas said again.

Unlike

Parmenides, Beethoven apparently viewed weight as something positive. Since the

German word

schwer

means both "difficult" and

"heavy," Beethoven's "difficult resolution" may also be

construed as a "heavy" or "weighty resolution." The

weighty resolution is at one with the voice of Fate (

"Es muss

sein!");

necessity, weight, and value are three concepts inextricably

bound: only necessity is heavy, and only what is heavy has value.

This is a conviction born of Beethoven's music, and although we cannot

ignore the possibility (or even probability) that it owes its origins more to

Beethoven's commentators than to Beethoven himself, we all more or less share,

it: we believe that the greatness of man stems from the fact that he

bears

his fate as Atlas bore the heavens on his shoulders. Beethoven's hero is a

lifter of metaphysical weights.

Tomas approached the Swiss border. I imagine a gloomy, shock-headed

Beethoven, in person, conducting the local firemen's brass band in a farewell

to emigration, an

"Es Muss Sein "

march.

Then Tomas crossed the Czech border

and was welcomed by columns of Russian tanks. He had to stop his car and wait a

half hour before they passed. A terrifying soldier in the black Uniform of the

armored forces stood at the crossroads directing traffic as if every road in

the country belonged to him and him alone.

"Es muss sein!"

Tomas repeated to himself, but then he began to doubt. Did it really have to

be?

Yes, it was unbearable for him to

stay in Zurich imagining Tereza living on her own in Prague.

But how long would he have been

tortured by compassion? All his life? A year? Or a month? Or only a week?

33

34

How

could he have known? How could he have gauged it? Any schoolboy can do

experiments in the physics laboratory to test various scientific hypotheses.

But man, because he has only one life to live, cannot conduct experiments to

test whether to follow his passion (compassion) or not.

It was with

these thoughts in mind that he opened the door to his flat. Karenin made the

homecoming easier by jumping up on him and licking his face. The desire to fall

into Tereza's arms (he could still feel it while getting into his car in

Zurich) had completely disintegrated. He fancied himself standing opposite her

in the midst of a snowy plain, the two of them shivering from the cold.

From

the very beginning of the occupation, Russian military airplanes had flown over

Prague all night long. Tomas, no longer accustomed to the noise, was unable to

fall asleep.

Twisting and

turning beside the slumbering Tereza, he recalled something she had told him a

long time before in the course of an insignificant conversation. They had been

talking about his friend Z. when she announced, "If I hadn't met you, I'd

certainly have fallen in love with him."

Even then, her

words had left Tomas in a strange state of melancholy, and now he realized it

was only a matter of chance that Tereza loved him and not his friend Z. Apart

from her consummated love for Tomas, there were, in the realm of possibility,

an infinite number of unconsummated loves for other men.

35

We all reject out

of hand the idea that the love of our life may be something light or

weightless; we presume our love is what must be, that without it our life would

no longer be the same; we feel that Beethoven himself, gloomy and awe-inspiring,

is playing the

"Es muss sein!"

to our own great love.

Tomas often thought of Tereza's

remark about his friend Z. and came to the conclusion that the love story of

his life exemplified not

"Es muss sein! "

(It must be so), but

rather

"Es konnte auch anders sein"

(It could just as well be

otherwise).

Seven years earlier, a complex

neurological case

happened

to have been discovered at the hospital in

Tereza's town. They called in the chief surgeon of Tomas's hospital in Prague

for consultation, but the chief surgeon of Tomas's hospital

happened

to

be suffering from sciatica, and because he could not move he sent Tomas to the

provincial hospital in his place. The town had several hotels, but Tomas

happened

to be given a room in the one where Tereza was employed. He

happened

to

have had enough free time before his train left to stop at the hotel restaurant.

Tereza

happened to

be on duty, and

happened

to be serving Tomas's

table. It had taken six chance happenings to push Tomas towards Tereza, as if

he had little inclination to go to her on his own.

He had gone back to Prague because

of her. So fateful a decision resting on so fortuitous a love, a love that

would not even have existed had it not been for the chief surgeon's sciatica

seven years earlier. And that woman, that personification of absolute fortuity,

now again lay asleep beside him, breathing deeply.

It was late at night. His stomach

started acting up as it tended to do in times of psychic stress.

Once or twice her breathing turned

into mild snores. Tomas felt no compassion. All he felt was the pressure in

his stomach and the despair of having returned.

Soul and Body

It

would be senseless for the author to try to convince the reader that his

characters once actually lived. They were not born of a mother's womb; they

were born of a stimulating phrase or two or from a basic situation. Tomas was

born of the saying

"Einma! ist keinmal."

Tereza was born of

the rumbling of a stomach.

The first time she went to Tomas's

flat, her insides began to rumble. And no wonder: she had had nothing to eat

since breakfast but a quick sandwich on the platform before boarding the train.

She had concentrated on the daring journey ahead of her and forgotten about

food. But when we ignore the body, we are more easily victimized by it. She

felt terrible standing there in front of Tomas listening to her belly speak

out. She felt like crying. Fortunately, after the first ten seconds Tomas put

his arms around her and made her forget her ventral voices.

39

Tereza

was therefore born of a situation which brutally reveals the irreconcilable

duality of body and soul, that fundamental human experience.

A long time ago, man would listen

in amazement to the sound of regular beats in his chest, never suspecting what

they were. He was unable to identify himself with so alien and unfamiliar an

object as the body. The body was a cage, and inside that cage was something

which looked, listened, feared, thought, and marveled; that something, that

remainder left over after the body had been accounted for, was the soul.

Today, of course, the body is no

longer unfamiliar: we know that the beating in our chest is the heart and that

the nose is the nozzle of a hose sticking out of the body to take oxygen to the

lungs. The face is nothing but an instrument panel registering all the body

mechanisms: digestion, sight, hearing, respiration, thought.

Ever since man has learned to give

each part of the body a name, the body has given him less trouble. He has also

learned that the soul is nothing more than the gray matter of the brain in

action. The old duality of body and soul has become shrouded in scientific

terminology, and we can laugh at it as merely an obsolete prejudice.

But just make someone who has

fallen in love listen to his stomach rumble, and the unity of body and soul,

that lyrical illusion of the age of science, instantly fades away.

40

Tereza

tried to see herself through her body. That is why, from girlhood on, she would

stand before the mirror so often. And because she was afraid her mother would

catch her at it, every peek into the mirror had a tinge of secret vice.

It was not vanity that drew her to

the mirror; it was amazement at seeing her own "I." She forgot she

was looking at the instrument panel of her body mechanisms; she thought she saw

her soul shining through the features of her face. She forgot that the nose was

merely the nozzle of a hose that took oxygen to the lungs; she saw it as the

true expression of her nature.

Staring at herself for long

stretches of time, she was occasionally upset at the sight of her mother's

features in her face. She would stare all the more doggedly at her image in an

attempt to wish them away and keep only what was hers alone. Each time she

succeeded was a time of intoxication: her soul would rise to the surface of her

body like a crew charging up from the bowels of a ship, spreading out over the

deck, waving at the sky and singing in jubilation.

She

took after her mother, and not only physically. I sometimes have the feeling

that her entire life was merely a continuation of her mother's, much as the

course of a ball on the billiard table is merely the continuation of the

player's arm movement.

41

44

Indeed, was she not

the principal culprit determining her mother's fate? She, the absurd encounter

of the sperm of the most manly of men and the egg of the most beautiful of women?

Yes, it was in that fateful second, which was named Tereza, that the botched

long-distance race, her mother's life, had begun.

Tereza's mother

never stopped reminding her that being a mother meant sacrificing everything.

Her words had the ring of truth, backed as they were by the experience of a

woman who had lost everything because of her child. Tereza would listen and

believe that being a mother was the highest value in life and that being a

mother was a great sacrifice. If a mother was Sacrifice personified, then a

daughter was Guilt, with no possibility of redress.

Of course, Tereza

did not know the story of the night when her mother whispered "Be

careful" into the ear of her father. Her guilty conscience was as vague as

original sin. But she did what she could to rid herself of it. Her mother took

her out of school at the age of fifteen, and Tereza went to work as a waitress,

handing over all her earnings. She was willing to do anything to gain her

mother's love. She ran the household, took care of her siblings, and spent all

day Sunday cleaning house and doing the family wash. It was a pity, because she

was the brightest in her class. She yearned for something higher, but in the

small town there was nothing higher for her. Whenever she did the

45

clothes, she kept a

book next to the tub. As she turned the pages, the wash water dripped all over

them.

At home, there was no such thing as

shame. Her mother marched about the flat in her underwear, sometimes braless

and sometimes, on summer days, stark naked. Her stepfather did not walk about

naked, but he did go into the bathroom every time Tereza was in the bath. Once

she locked herself in and her mother was furious. "Who do you think you

are, anyway? Do you think he's going to bite off a piece of your beauty?"

(This confrontation shows clearly

that hatred for her daughter outweighed suspicion of her husband. Her

daughter's guilt was infinite and included the husband's infidelities. Tereza's

desire to be emancipated and insist on her rights—like the right to lock

herself in the bathroom—was more objectionable to Tereza's mother than the

possibility of her husband's taking a prurient interest in Tereza.)

Once her mother decided to go naked

in the winter when the lights were on. Tereza quickly ran to pull the curtains

so that no one could see her from across the street. She heard her mother's

laughter behind her. The following day her mother had some friends over: a

neighbor, a woman she worked with, a local schoolmistress, and two or three

other women in the habit of getting together regularly. Tereza and the

sixteen-year-old son of one of them came in at one point to say hello, and her

mother immediately took advantage of their presence to tell how Tereza had

tried to protect her mother's modesty. She laughed, and all the women laughed

with her. "Tereza can't reconcile herself to the idea that the human body

pisses and farts," she said. Tereza turned bright red, but her mother

would not stop. "What's so terrible about that?" and in answer to her

own question she broke wind loudly. All the women laughed again.