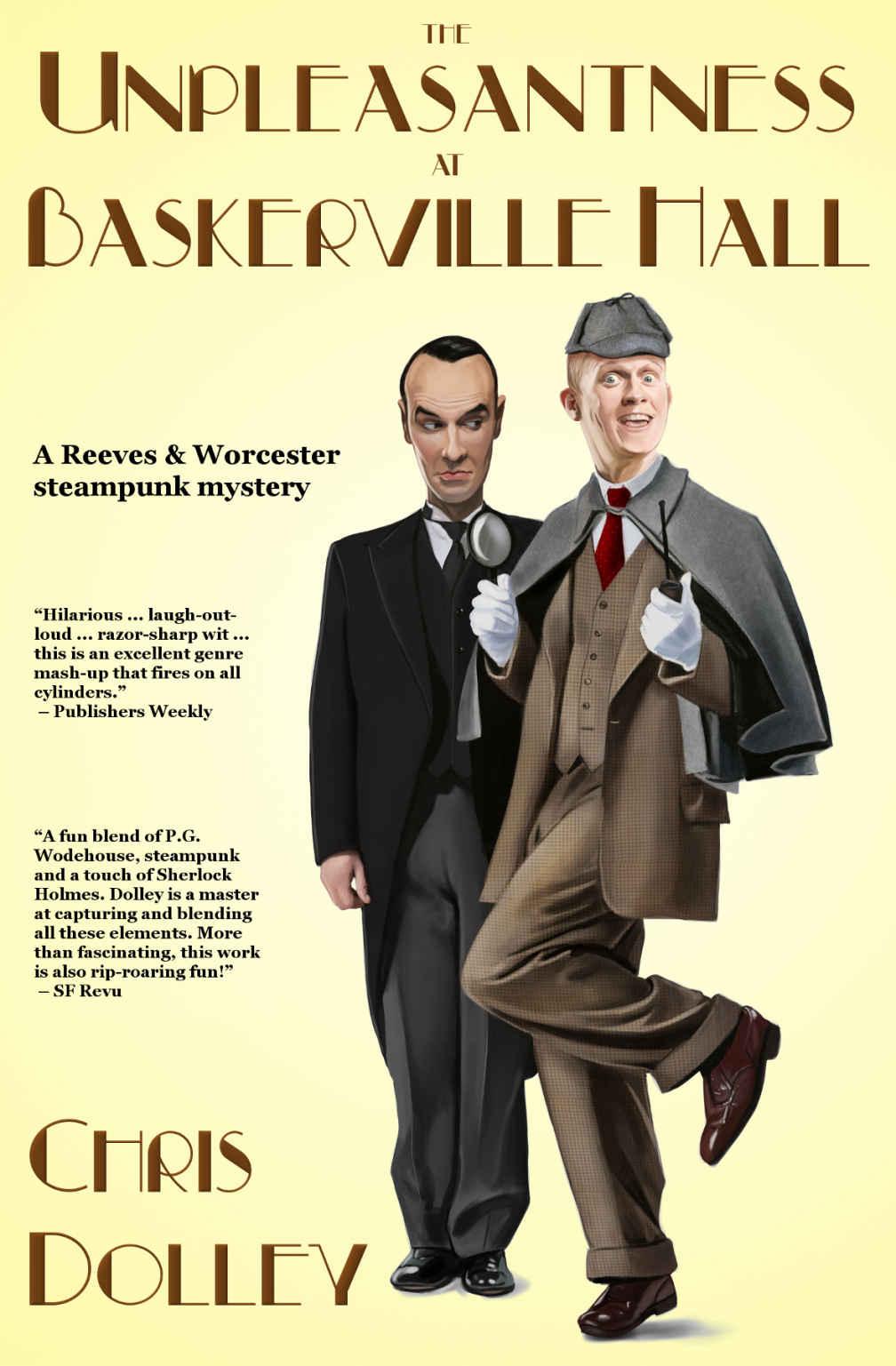

The Unpleasantness at Baskerville Hall (Reeves & Worcester Steampunk Mysteries Book 4)

Read The Unpleasantness at Baskerville Hall (Reeves & Worcester Steampunk Mysteries Book 4) Online

Authors: Chris Dolley

Tags: #Jeeves, #Humor, #Mystery, #Holmes, #wodehouse, #Steampunk

The Unpleasantness

at Baskerville Hall

Chris Dolley

This is a work of fiction. All characters, cannibals, mad scientists, locations, and events portrayed in this book are fictional or used in an imaginary manner to entertain, and any resemblance to any real people, situations, or incidents is purely coincidental.

All Rights Reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form.

Copyright © 2016 by Chris Dolley

Published by Book View Café

ISBN 13: 978-1-61138-554-0

Cover art by Mark Hammermeister

Cover design by Chris Dolley

Steampunk Font © Illustrator Georgie - Fotolia.com

One

you believe in star cross’d lovers, Reeves?”

you believe in star cross’d lovers, Reeves?”

“Sir?”

“Romeo and Juliet, Reeves. I fear that’s what’s happening to me and Emmeline. Minus the asp.”

“The asp was Cleopatra, sir.”

“Really? I didn’t know the asp had a name. Family pet, was it?”

The things one learns when one’s valet has a giant steam-powered brain. I puffed on a contemplative cheroot while Reeves mixed my mid-morning cocktail.

“Am I to understand that your aunt Bertha remains opposed to the match, sir?”

“If anything her opinion has hardened, Reeves. I have spent the last hour being lectured as to what is, and what is not, acceptable behaviour for prospective Mrs Reginald Worcesters. Chaining oneself to railings — even in the better neighbourhoods — features strongly in the unacceptable pile. Top billing, though, is reserved for having one’s photograph appear in the

Tatler

.”

“Your aunt is opposed to that illustrated magazine, sir?”

“Far from it, Reeves. Aunt Bertha is much taken with the

Tatler

. As are her circle. I should have said it’s not so much having one’s picture published as to the content of said picture. Being dragged off the Home Secretary by a burly policeman whilst attempting to give the former a ripe one across the mazard with a furled parasol is apparently the height of bad form.”

“Miss Emmeline

is

a very spirited young lady, sir.”

“That’s what

I

said. Give her the vote and all would be sweetness and light. Home Secretaries would be safe to walk the streets once more and the only casualties would be the purveyors of fine gauge chains for the progressive woman.”

“Indeed, sir. Have you heard from Miss Emmeline since her departure?”

“I have not, Reeves. Which worries me greatly.”

It wasn’t only Aunt Bertha who’d taken against the match. The Dreadnought clan and, in particular, Emmeline’s mother, had decided that her daughter could do better. Two days ago they’d packed her off to Baskerville Hall for a fortnight in the country with the hope she’d bag the heir to the Baskerville-Smythe title.

Not that she had gone willingly. Words had been exchanged. Food had been refused, and a small barricade — which she’d manned for a full twenty-four hours! — had been constructed around her bedroom door.

It took Reeves — perched on a ladder propped up outside her bedroom window — to persuade the young firebrand that feigned acquiescence was the best way to thwart her family’s designs.

Reeves has always been big on feigned acquiescence.

But I had my doubts. Reeves may have thought the family would soon tire of trying to marry her off to every Lord Tom, Dick and Algernon, but what if they didn’t? And what if she fell for one of these suitors? Emmeline had promised to write to me every day, but it was two days now and I hadn’t received a single letter!

“I am a worried man, Reeves. What if this Baskerville-Smythe chap has turned her head? It’s always happening in books. Modern girls rarely marry the chap they’re engaged to on page seven.”

“Miss Emmeline is a stalwart and strong-minded young lady, sir.”

“So was Lady Sybil in

The Ravishing Sporran.

But one sight of a man in a kilt and she was undone, Reeves. Putty in his roving Highland hands. Do they wear kilts in Devonshire?”

“Not that I have heard, sir.”

“Well that’s

one

stroke of luck.”

I took a long sip of fortifying cocktail before rising from my armchair. This Baskerville-Smythe chap would probably rate an entry in

Milady’s Form Guide to Young Gentlemen.

What better way to discover what I was up against?

I found the guide in the bookcase and leafed through it until I found the entry for Henry Baskerville-Smythe. It read:

Dashing and well turned out colt. Excellent pedigree, good conformation. Unraced for two years as has been out of the country. Not expected to be riderless for long! Very fast on the gallops.

“I don’t like the sound of this, Reeves. Have you seen it?”

I handed him the form guide.

“H’m,” said Reeves.

“What do you mean ‘h’m,’ Reeves? Is that a good ‘h’m’ or a bad ‘h’m’?”

“I think this is a positive development, sir.”

“You do? How do you work that out?”

“An entry such as this, sir, is likely to attract a large number of young ladies and their families. Miss Emmeline will have stiff competition.”

“She will?”

“I would expect there to be

several

young ladies staying at Baskerville Hall this very fortnight, sir, each with instructions to monopolise Mr Baskerville-Smythe’s attention.”

“I don’t know, Reeves. I can’t bear another twelve days like this, imagining the worst. We Worcesters are men of action. Pack my bags, Reeves. We leave for Baskerville Hall within the hour.”

Reeves gave me his disapproving face. “I would strongly counsel against such a move, sir. Miss Emmeline

did

say that the Baskerville-Smythes had been given firm instructions to turn you away should you happen to call.”

I waved a dismissive hand at Reeves’ objections. “A mere formality, Reeves. We shall go in disguise.”

Reeves coughed.

“It’s all right, Reeves. I’m not contemplating a long beard and a parrot. A false name should suffice. None of the Baskerville-Smythes have ever met me. I shall once more become Nebuchadnezzar Blenkinsop. And you can be my valet Montmorency.”

Reeves’ left eyebrow rose like a restrained, but clearly startled, salmon.

“I think not, sir. It has been my observation that families are loathe to extend hospitality to strangers who arrive unannounced.”

“Then I’ll introduce myself as a distant relative — one cannot turn away family. I should know.”

Reeves was still unconvinced, but at least he’d wrestled back control of his eyebrows.

“It would have to be a

very

distant relative, sir. Questions will be asked, and suspicions aroused should your knowledge of family matters fall short of expectations.”

A good point. I took a long sip of my mid-morning bracer and waited for the restorative nectar to pep up the little grey cells.

“How about an imaginary scion, Reeves? Most families have a third or fourth son sent out to the colonies to find their fortune. I’ll be the product of a secret marriage conducted in the Australian outback.”

~

A quick perusal of

Who’s Who

uncovered a wealth of Baskerville-Smythes, but few of them were extant. Henry was an only son, and his father, Sir Robert — a widower for nigh on ten years — had outlived both his wife and three brothers. The only relative above ground at Baskerville Hall was a Lady Julia Noseley, Sir Robert’s sister-in-law.

“It says here that Henry’s in South Africa serving with his regiment,” I said.

“That

is

last year’s edition, sir.

Milady’s Form Guide to Young Gentlemen

did mention that mister Henry had recently returned from abroad.”

“I don’t like this, Reeves. He’ll have a uniform. They’re worse than kilts!”

I read further, desperate to find a suitable distant relative of the right age. One of Sir Robert’s brothers, Cuthbert, had moved to South America. That was certainly distant enough. He’d married a local girl and had a son, Roderick. Cuthbert had then died of yellow fever and his wife had died of scarlet fever. Roderick had managed to survive both his parents — presumably because the local fevers had run out of colours — but was believed to have died a few years later when he was struck by the Buenos Aires to Mar del Plata express.

“These Baskerville-Smythes are a very unlucky bunch, Reeves. It’s a wonder there are any of them left.”

I was then struck with a notion. Roderick Baskerville-Smythe was only

presume

d dead. And he was born within a year or two of me. And he’d stayed in Argentina — no doubt with his mother’s family — after he’d been orphaned. It was unlikely he’d ever met anyone from his father’s side of the family.

“I have it, Reeves! Send a telegram to Baskerville Hall at once. Roderick Baskerville-Smythe has returned from South America!”

Reeves appeared not to share the young master’s enthusiasm.

“I would not recommend such an action, sir. The appearance — as if from nowhere — of a long lost and, hitherto, believed deceased, relative, would, in my opinion, be viewed with great suspicion.”

“Nonsense, Reeves. It would be an occasion of great joy. Fatted calves would be called for. There’s even a passage in the Bible. Joseph, wasn’t it? The one with the oofy coat? Returning home after seven years of high living abroad and being treated by his father to a fatted calf supper? And Joseph hadn’t even had a close shave with the Cairo to Antioch express!”

“In the parable of the Prodigal Son, sir, to which I believe you allude, the young gentleman was only received favourably by his father. His older brother was somewhat vexed. You would be returning to an uncle, an aunt and a cousin. I fear they would side with the older brother upon this matter, and speculate upon the motive behind your reappearance.”

“They might think I was there to touch ’em for a few quid?”

“Indeed, sir.”