The Vatard Sisters (29 page)

Ah, his pride was cut to the quick. And yet, when he thought of Céline, he no longer had a vision of the woman who’d so unworthily deceived him, he no longer saw in her anything but the sensual and sweet mistress. He had a sudden realisation of the injustices and the cruelties he’d committed; he reproached himself for his facetiousness, his haughty caresses; he acknowledged that he’d been wrong, that he should have excused her ridiculous expressions and tastes on account of her high spirits. He felt tender towards her, was not far short, frankly, of adoring her, but then in a sudden flash the memory of her betrayal struck him. He remembered Céline’s outburst that she would rather be beaten than be treated like a pathetic idiot, and for a minute he regretted not having satisfied this masochistic urge of hers; then he became calmer, admitting that he could never have consented to slap a woman, and, undressed and seated in bed, he recalled the indignities his other mistresses had visited on him.

‘Clémence, ah yes, she left me without even writing; Suzanne, I never knew why; Héloïse, because I kept a close watch on her; Eugénie, because I didn’t keep a close watch on her!’ And he repeated melancholically to himself: ‘When I think that Héloïse, who was so proud of her upbringing, contrived to pilfer my boxwood face-powder casket and that I’ve never heard a word from her since, I’ve no right to get angry with Céline who, in spite of not having two sous to rub together, never robbed me of anything.’

And overwhelmed by all these memories of broken liaisons he was stirring up, moved by all these faces passing before his eyes, smiling when in the bedroom and spitting abuse in his face when they left him, he blew out the lamp.

‘I’m so stupid,’ he murmured, ‘it shouldn’t surprise me. Since it goes without saying that all women behave badly when they dump us, the good Lord himself wouldn’t expect Céline, who was the most uncouth of them all, to have shown any more consideration than the rest. To be fair, that wouldn’t have been very realistic.’ And he added with a forced smile: ‘Even so, it isn’t very funny; I’m going to miss that girl, I think I’m going to miss her silliness. Ah, damn it, I really wish it were two months from now.’

‘It’s possible,’ replied Ma Teston, ‘but if you continue to harass me like that, I’ll have you sacked by the boss.’

‘You wouldn’t dare,’ Chaudrut answered simply, leaning back a little and slipping his hands inside the cord he was using for a belt.

Ma Teston immediately turned her back on him and headed towards the boss’s office.

The supervisor, who’d gone out more than two hours ago, returned with a heavy basket in her arms. All the women ran over to her crying: ‘Let’s see!’ The supervisor lifted the towel covering the wicker basket to reveal twelve flat plates, six soup plates, two hors-d’oeuvres dishes, a round platter, a salt shaker, a mustard pot, and a large soup bowl.

‘It’s porcelain!’ blurted fat Eugénie.

‘Well, do you think that when I want to make people happy,’ exclaimed the supervisor, ‘I wouldn’t buy them the best?’

The service was passed from hand to hand. Some of the bindery women held the plates up to see the daylight through them, others tapped them with their fingernails and listened carefully to hear if they were cracked; all left their black fingerprints on the shining enamel. As it was being circulated the soup bowl was almost dropped. The supervisor immediately stopped the procession of porcelain unfurling from one end of the workshop to the other, and with a thousand precautions, piled these fabulous products from Montereau and Creil back in her basket, which she placed next to her chair where she worked.

‘Désirée is going to be very chuffed!’ said Céline. ‘That’s a beautiful wedding present you’re giving her, ma’am.’

‘She’s getting married? So what?’ chimed in the girl suffering with her teeth, ‘what’s so great about that? My word, you’d think it was something amazing. All this fuss over nothing. The firm wouldn’t give as much as a radish to us, if like Désirée we wanted the luxury of pissing out legitimate babies in the future!’

‘To you, certainly not,’ replied the supervisor, ‘no one’s going to make any sacrifices for a drudge like you!’

The girl was going to reply, but someone alerted her that a well-dressed woman wanted to see her.

She returned a few minutes later, triumphantly waving a lilac polka-dot camisole.

‘That was the old trout dropping by,’ she replied to fat Eugénie’s questions. ‘She asked me why I didn’t go to the Young Women’s Catholic Association meeting on Sunday; meetings my eye, I don’t care about them. I let her rabbit on; I said I’d had stomach cramps, and she fell for it. She even gave me this camisole.’

The whole workshop burst out laughing.

Ma Teston, who was slowly shuffling back in, was outraged. ‘When a person plays the little hypocrite like you, the least they could do after having swindled a charitable woman is not call them an old trout.’

But apart from one or two girls who didn’t breathe a word, everyone else approved this way of behaving.

‘Well, too bad for her,’ exclaimed one, ‘why do these ’ere prudes come round bothering us anyway?’ ‘Serves ’er right,’ cried another, ‘what a disgusting bunch they are. She came sniffing round to see if she could smell a man on you. That sort spend every morning ogling young men on the sly, and every evening living it up at their posh parties. No thank you. We don’t need leeches like her.’

‘Hey, Old-Ma-Morality,’ said Chaudrut, ‘how did your audience with the president go? Is it today they’re going to give me my cards?’

‘Monsieur isn’t there,’ snorted Ma Teston angrily, ‘but rest assured you’ll get what’s coming to you.’

Then a joke that had been going round the workshop for the last year and a half was repeated, that Chaudrut had fallen in love with Ma Teston and was only waiting for her to be widowed in order to ask for her hand.

The old woman was outraged.

‘Him! Him! A good-for-nothing of his sort! Oh dear me, no, I’d rather do anything than that!’ And sure of hitting him where it hurt she cast a scornful glance at Chaudrut and said: ‘Why, he’s old enough to be my father!’

‘Marry you? Not on your life!’ riposted the old man, stung by this reference to his advanced age.

But as always the supervisor intervened.

‘Now then, back to work! Really, no one does a thing anymore. On the flimsy pretext of drinking to Auguste’s health, every man and woman here has been boozing for the last week. But since he’s married what’s the use of that now? Not to mention the fact that I’m certain someone’s fricasseed Puss-puss; it’s a long time since anyone’s seen him and I’m not blind, there are people here whose hands are covered in scratches.’

She was interrupted by the rollers of the folding machine striking the tables. ‘There she is!’ exclaimed a group of women, and Désirée, all perky, made her entrance.

The supervisor gathered up her basket and placed it on the table in front of the young girl, who blushed, stepped back, clasped her hands together, then threw herself into the arms of the supervisor, almost suffocating her with hugs.

‘Oh, I’m so happy, oh, yes I am!’ she repeated, quite choked. ‘Oh, it’s beautiful!’ And she reverently delved in the hamper, gingerly taking out the hors-d’oeuvres dishes, lifting the lid of the soup bowl, pulling out the salt shaker, which she held by the tip and swung gaily around in the air. ‘Ah, a mustard pot!’ And the mustard pot was passed around the women; they examined the slot, fashioned in the edge of the lid to hold a little spoon; they enthused over the elegance of this lid, topped with a dainty little knob so you could lift it.

Dusk was beginning to creep slowly into the workshop. Through the murky windows a pale, faded daylight spread over the tables, unfurled into shadowy corners, dying in a final burst on a bed of yellow paper trimmings.

To the protests of the supervisor, who was annoyed at watching them loaf about, the women, gathered in a circle and whiling away the time, replied that they could no longer see to work.

So someone hollered for a man who came with his wax taper, and all the gaslights blazed, casting the laughter of their fire over the penetrating melancholy of the approaching night.

Everyone returned to their seats.

‘So the wedding’s set for Saturday next?’ said the supervisor.

‘Yes ma’am,’ replied Désirée.

The supervisor bent over her work and quietly asked herself this question, which she’d never been able to answer in the thirty years she had worked at the bindery:

‘Girls who go out on the binge are nearly always terrible workers; those who don’t, earn good money but then they get married and become worse than useless because they no longer come to work at all. What can be done?’ And, rethreading her needle, she went on: ‘That’s another fine binder gone. Once she’s married, Désirée will be like all the others, she’ll give up her job; I’ll have to find some decent young girl as a replacement.’And at the thought of the search she’d have to make in order to unearth one, she shook her head and sighed a sigh that spoke volumes.

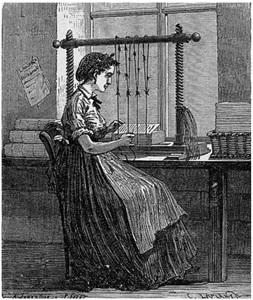

“After two silently smoked pipes, he would put Eulalie to bed, and, in a bad mood, yawn until ten o’clock…” (

here

) A dry-point by Jean François Raffaëlli used in the illustrated edition of

Les Soeurs Vatard

(Ferroud, 1909).

“Putting on his coat, he followed the crowd of workers who were all leaving in a group; he caught up with Désirée at the doorway and suggested they walk back together…” (

here

) A dry-point by Jean François Raffaëlli from the illustrated edition of

Les Sœurs Vatard

.

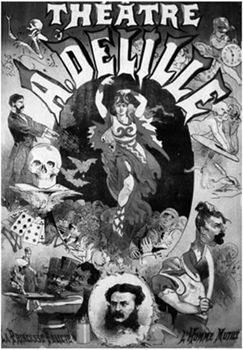

Publicity poster for the Theatre Delille.

Publicity poster for the Folies-Delille. Bobino.