The Vatard Sisters (30 page)

A contemporary illustration of a brocheuse, or worker in a book bindery.

A contemporary caricature of Zola and the Naturalists entitled

Zola and his school.

Caricatures of this period were often extremely graphic and scatalogical, with pigs,

merde

and chamber-pots frequently being used as symbols associated with Zola and the other Naturalists.

The publisher of

Les Sœurs Vatard,

Georges Charpentier (1846-1905).

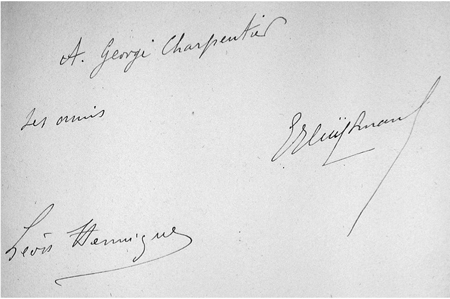

Dedication page of

Pierrot sceptique

, signed to Georges Charpentier by Huysmans and Léon Hennique in 1881.

Part of the first page of the manuscript of

Les Sœurs Vatard.

I

39

…

All right, ladies, a little quiet

. This phrase is repeated almost word for word a number of times, showing that even though Huysmans was consciously situating his book within the conventions of Naturalism in terms of its subject matter, he was also self-consciously stylising aspects of the novel in a non-Naturalist way at the level of language. Huysmans frequently used the repetition of words and phrases both in his prose poems and his novels to achieve a certain kind of literary effect.

39

…

He died, that soldier sto–ic.

Lines from a popular song about one of the heroes of the French Revolution, General François Marceau (1769-1796). The refrain runs: “He has gone, that soldier stoic/To fight against Kings on the Rhine/Singing loud and proud/Long live the Republic!” Although the song is specifically about the French Revolution, the reference to the Rhine would no doubt have had a more contemporary significance given the loss of Alsace and Lorraine in 1871, after the Franco-Prussian war.

40

…

Have pity on my suff–er-in’

. These lines are adapted from a popular patriotic song,

La fille d’auberge

(

The Barmaid

), written by Gaston Villemer and Lucien Delormel, which laments the annexation of Alsace and Lorraine by Germany after the Franco-Prussian War. The song is about a serving maid in an inn near Alsace who turns away German soldiers saying that they only serve French soldiers and that one day the Germans will be chased out of Alsace.

41

…But whether the branches.

These lines are from another popular ballad

, L’Amour n’a pas de saison (Love knows no season)

.

II

45

…

Débonnaire & Co

. Huysmans’ idea to use a bookbindery as the backdrop for his novel was no doubt inspired by the bookbinding firm owned by his family, and which he inherited after his mother’s death. See the introduction for more details.

45

…

wicker-hamper of fat

. Huysmans uses the word

gabion

in the original, which was an early form of sandbag, being a large wickerwork cylinder, about two feet in diameter and three or four feet tall. They were used to form barriers around trenches by filling a row of them with the earth that had been dug out.

47

…

a dicky stomach and could no longer drink

. In the original Huysmans uses the phrase

estomac en meringue

, an expression meaning to have a stomach as weak and fragile as a meringue.

49

…

the Hospital Sisters of Saint-Thomas de Villeneuve

. In the original Huysmans refers to it by its shorthand name

Dames Saint-Thomas de Villeneuve

. He mentions the same institution in

La Cathédrale

,

L’Oblat

and

Les Foules de Lourdes

, mostly in relation to the statue of the

Vierge noire

(the Black Virgin), which was housed there.

50

…

that slut

. In the original Huysmans uses the word

volaille

, which literally means ‘fowl’ or ‘poultry’, but which in the nineteenth century was also slang for a prostitute or a woman of easy virtue.

51

…

patting his thigh with his hand flat

. Although this insulting gesture isn’t used today, it seems fairly clear that it has a sexual meaning, equivalent to ‘Screw you!’ or ‘Fuck you!’

52

…after the model of Delaroche’s

. Paul Delaroche (1797-1856) was a French painter renowned for his large historical and religious canvases. His iconic

Virgin at the foot of the Cross

, or

Mater dolorosa,

was painted in 1858 and is now in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

52

…

toddlers sliding around on their backsides.

In the original Huysmans uses the expression,

se frottant à l’écorche-cul,

the definition of which is given in

La Flore pornographique

, a glossary of phrases and bits of slang used by the Naturalists, and published in 1883 by Antoine Laporte, under the pseudonym Ambroise Macrobe.

53

…

Chez Ragache

. This was a cabaret near the Barrière du Maine, 53 rue de Sèvres, that specialised in cheap meals. The establishment was also mentioned in

Les Excentriques

(1852) a collection of literary portraits by Jules Husson (1821-1889), who wrote under the name of Champfleury and was an influential figure in the Realist movement.

54

…cheap wine

. Huysmans uses the word

campêche

, the name of a tree from which a red colouring was produced. According to

Argot and Slang: A New French And English Dictionary of the Cant Words, Quaint Expressions, Slang Terms and Flash Phrases used in the High and Low Life of Old and New Paris

by Albert Barrère (London: Whittaker, 1889), the term

campêche

was commonly used to signify ‘bad wine, of which the ruby colour is often due to an adjunction of logwood’.

55

…

a glass of Rigolboche and something to eat.

In the original Huysmans uses the term

lichoter un rigolboche

. Although this is defined in Albert Barrère’s

Argot and Slang

as ‘to make a hearty meal,’ the expression could equally refer in this case to an actual drink of the period called a ‘Rigolboche’. Huysmans also used the term

lichoter

, a slang word for drinking, in

Marthe

(1876), and he mentions Rigolboche as an alcoholic drink in one of his early prose pieces

L’Ambulante

(published in

La Cravache parisienne

in December 1876 and reprinted in

Croquis parisiens

, 1880), where he points out an advertising slogan for it on the wall of a cabaret in the Place Pinel. The drink, a kind of cherry liqueur, was named after a popular Parisian dancer, Marguerite Badel (1842-1920), who was nicknamed ‘Rigolboche’ and renowned for her

cancan

during the Second Empire. As the phrase is a little ambiguous and supports both interpretations I have included a reference to both drinking and eating.

55

…

wheel-of-fortune

. The word

tourniquet

in the original makes reference to a wooden game of chance that drinkers would sometimes use to determine who would pay for a round.

63

…

the Banquet d’Anacreon

. Formerly situated at 47 Boulevard Saint-Martin, the

Banquet d’Anacreon

combined entertainment and food. William Makepeace Thackeray mentions it in a letter of 1850 to Mrs Brookfield: ‘The Banquet d’Anacreon is a dingy little restaurant on the boulevard where all the plays are acted…’

63

…

the Mille-Colonnes

. Situated at 20 Rue de la Gaité, Montparnasse, the Mille-Colonnes was a dance hall-cumrestaurant, with the dance hall on one side of the garden and the restaurant on the other.

63

…

the Grados dance hall

. The Bal Grados was a low-class dive on the Rue de Gaité. Huysmans also mentions it in a piece he wrote for

Le Gaulois

in June 1880, and André Gill, in his

Correspondance et memoirs d’un caricaturiste (1840-1885)

, remembers that the Rue de la Gaité used to be ‘the liveliest street in the world’, and that the Bal Grados was a ‘rollicking dance hall’.

64

…

put a spoon in each glass

. Another instance of Huysmans’ attention to detail, spoons being placed in glass before pouring in a hot liquid in order to prevent the glass cracking.

III

71

…

sluttified

. In the original Huymans uses his own neologism,

ensalopé

, which is derived from the verb

saloper

, which means to dirty or spoil and is often used in relation to prostitutes or general sexual debauchery.

71

…

sauce ravigote

. Ravigote sauces are highly seasoned with shallots or onion, capers and herbs:

ravigoté

connotes reinvigorated or freshened up. It is generally served with fish, fowl, eggs and, traditionally, with

tête de veau

, jellied hare, head cheese, paté or calves’ brains.

71

…

perfumed beard

. Huysmans uses a couple of slangy expressions that make the precise meaning a little unclear (

barbe à la rose et qui aurait fait de la mousse avec les lèvres, en parlant

). Although

fait de la mousse

does have a literal meaning and could be interpreted as ‘foaming at the mouth, or spitting, when he spoke’, this would not seem to make sense given the references to the gentleman’s silk hat and fancy beard. The allusion Huysmans is trying to make may be to do with the sense in which

faire de la mousse

, implies he is so clean he could blow soap-bubbles.

72

…

A villain and a drunkard

. This doesn’t do justice to the untranslatable phrase used by Huysmans,

tendre comme un moineau et soulard comme une grive

(literally, ‘tender as a sparrow and drunk as a thrush’). In French the word

moineau

is often coupled with

vilain

or

sale

and is used to describe an untrustworthy or disreputable man, while the

grive

has long been used in metaphors of drunkenness as it was believed that the bird had a fondness for eating grapes.