The Vietnam Reader (15 page)

Read The Vietnam Reader Online

Authors: Stewart O'Nan

RICK. I don’t even know why you’d think you did.

OZZIE. We kill you is what happens.

RICK. That’s right.

OZZIE. And then, of course, we die, too … Later on, I mean. And nothing stops it. Not words … or walls … or even guitars.

RICK. Sure.

OZZIE. That’s what happens.

HARRIET. It isn’t too bad, is it?

RICK. How bad is it?

OZZIE. He’s getting weaker.

HARRIET. And in a little, it’ll all be over. You’ll feel so grand. No more funny talk.

RICK. You can shower; put on clean clothes. I’ve got deodorant you can borrow. After Roses, Dave. The scent of a thousand roses.

He is preparing to take a picture—crouching, aiming,

HARRIET. Take off your glasses, David.

OZZIE. Do as you’re told.

RICK

(as David’s hands are rising toward the glasses to remove them).

I bet when you were away there was only plain water to wash in, huh? You prob’ly hadda wash in the rain.

(He takes the picture; there is a flash. A slide appears on the screen: A close-up of David, nothing visible but his face. It is the slide that, appearing as the start of the play, was referred to as “somebody sick.”

Now

it hovers, stricken, sightless, revealed.)

Mom, I like David like this.

HARRIET. He’s happier.

OZZIE. We’re all happier.

RICK. Too bad he’s gonna die.

OZZIE. No, no, he’s not gonna die, Rick. He’s only gonna nearly die. Only nearly.

RICK. Ohhhhhhhhhhhhh.

HARRIET. Mmmmmmmmmmmm.

And Rick, sitting, begins to play his guitar for David. The music is alive and fast. It has a rhythm, a drive of happiness that is contagious. The lights slowly fade.

From

Demilitarized Zones

J

AN

B

ARRY AND

W. D. E

HRHART

, E

DITORS

1976

Imagine

W. D. EHRHART

The conversation turned to Vietnam.

He’d been there, and they asked him

what it had been like: had he been in battle?

Had he ever been afraid?

Patiently, he tried to answer

questions he had tried to answer

many times before.

They listened, and they strained

to visualize the words:

newsreels and photographs, books

and Wilfred Owen tumbled

through their minds. Pulses quickened.

They didn’t notice, as he talked,

his eyes, as he talked,

his eyes begin to focus

through the wall, at nothing,

or at something deep inside.

When he finished speaking,

someone asked him

had he ever killed?

War Stories

P

ERRY

O

LDHAM

Have you heard Howard’s tape?

You won’t believe it:

He recorded the last mortar attack.

The folks at home have never heard a real

Mortar attack

And he wants to let them know

Exactly

What it’s like.

Every night he pops popcorn

And drinks Dr. Pepper

And narrates the tape:

Ka-blooie!

Thirty-seven rounds of eighty millimeter—

You can count them if you slow down the tape.

There’s an AK.

Those are hand grenades.

Here’s where the Cobras come in

And whomp their ass.

D. C. B

ERRY

A poem ought to be a salt lick

rather than sugar candy.

A preservative.

Something to make a tongue

tough enough to taste

the full flavor

of beauty and grief.

I would go to the dark

places where the

animals go;

they know

where the salt licks are

far

away from the barbed glitters of neon,

far

away from the bottles of booze

stacked like loaded rifles,

far

away into the gray-bone and

bleached silence.

I would go there now

before the slow explosion of Spring.

Already my tongue bleeds from

the yellow slash of Forsythia

that must be blooming

where you are.

In Celebration of Spring 1976

J

OHN

B

ALABAN

Our Asian war is over, squandered, spent.

Our elders who tried to mortgage lies

are disgraced, or dead, and already

the brokers are picking their pockets

for the keys and the credit cards.

In delta swamp in a united Vietnam,

a Marine with a bullfrog for a face

rots in equatorial heat. An eel

slides through the cage of his bared ribs.

At night, on the still battlefields, ghosts,

like patches of fog, lurk into villages

to maunder on doorsills of cratered homes,

while all across the U.S.A. in this 200th year

of revolution and the rights of man,

the wounded walk about and wonder where to go.

And today, in the simmer of lyric sunlight,

a chrysalis pulses in its mushy cocoon

under the bark on a gnarled root of an elm.

In the brilliant creek, a minnow flashes

delirious with gnats. The turtle’s heart

quickens its taps in the warm bank sludge.

As she chases a frisbee spinning in sunlight

a girl’s breasts bounce full and strong;

a boy’s stomach, as he turns, is flat and strong.

Swear by the locust, by dragonflies on ferns,

by the minnow’s flash, the tremble of a breast,

by the new earth spongy under our feet:

that as we grow old, we will not grow evil,

that although our garden seeps with sewage,

and our elders think it’s up for auction—swear

by this dazzle that does not wish to leave us—

that we will be keepers of a garden, nonetheless.

3

First Wave of Major Work

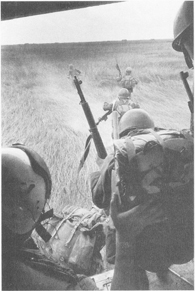

Vietnam, 1963. Troops land in a field near Tan Filing.

The year 1976 marked America’s Bicentennial and the election of President Jimmy Carter, the first President from the Deep South. Carter had been the governor of Georgia, and his status as a Washington outsider appealed to voters tired of the Nixon/Ford administrations’ corruption and back-room dealing. Carter’s ability to project an honest, down-home image helped him win the election, and for the first time in thirty years, America had a president with no direct tie to the Vietnam War.

American politicians in the mid-seventies naturally would have liked to put the war behind them, just as they would have liked America to forget the Watergate scandal, but the government’s abuse of the public trust was still fresh in the nation’s memory. During this era, skepticism was rampant, and all institutions were suspect. Carter himself referred to this as “the malaise,” and hoped that Americans would regain their faith.

Vietnam veterans had no part in this hopeful new beginning. Living reminders of a war that had split the country, they were rarely seen or heard, and when by chance they were, they seemed to fit stereotypes like the protest vet or psycho vet that were already growing old (see the introduction to

Chapter 4

for Hollywood’s portrayal of the vet at this time).

The first wave of major works changed this. Between 1976 and 1978, after years of being told by publishing houses that ‘Vietnam

doesn’t sell,’ veterans and journalists with Vietnam experience released powerful and controversial works that not only earned them literary awards and brilliant reviews, but became surprise bestsellers. Part of the first wave’s impact came from the fact that the general reader had never seen anything like these accounts. Though it had been years since the war had ended, these books were bringing the reader news, and unlike the institutions that had run and reported the war, the American people were still interested in finding out the truth about America’s role in Vietnam.

Ron Kovic’s

Born on the Fourth of July

(1976) is a nonfiction account of his stint in the Marines, his disabling injuries, and his struggles with the Veterans Administration. Written in an odd mix of first-and third-person narration, often drifting into stream-of-consciousness,

Born on the Fourth of July

shows Kovic’s progression from an idealistic teenager to a scared and bitter patient and finally to a committed political activist. The book was an immediate success; after years of rejection, Oliver Stone finally made it into a popular if not well-received movie in 1989.

Marine lieutenant James Webb’s first novel,

Fields of Fire

(1978), was a best-seller. In a realistic, if sometimes overwrought style, the book chronicles the Vietnam experience of several men in a Marine unit. It’s stuffed with technical expertise, and the characters are relatively flat and often take a backseat to the action. Critics sometimes label

Fields of Fire

old-fashioned, comparing it to World War II novels such as Norman Mailer’s

The Naked and the Dead

in its concentration on unit politics. Webb, a conservative Republican, was later appointed Secretary of the Navy by Ronald Reagan and wrote several other novels, none of which made as great an impact as his first.

Philip Caputo’s memoir

A Rumor of War

(1977) was also a best-selling first book. In a high literary style, the former Marine lieutenant and journalist describes his 1965-66 tour of duty, including an incident—a pair of murders—for which he faced a court-martial. This is another piece of nonfiction that reads like a novel in its attention to detail and setting of scenes. Caputo digs deep into important moral issues, and his explanations of the war and his own actions are provocative.

Of all the books to come out of the Vietnam War, journalist Michael Herr’s

Dispatches

(1977) is most often cited as the best, capturing the thrills, terror, and madness of the war. Written in a wild, anecdotal style,

Dispatches

nails the absurd contradictions (both moral and material) of the conflict and takes the reader seemingly everywhere in-country by chopper, touching down with Herr in the middle of the first rock ’n’ roll war. While Herr is writing nonfiction, he never lets the reader assume his objectivity, often focusing on his own strange, even parasitic role in the proceedings. And the stories that he tells or retells have the feel of legends or tall tales, even jokes. Later Herr would write parts of the scripts for both

Apocalypse Now

and

Full Metal Jacket