The Virgin Cure (11 page)

My darling Polly, It won’t be long now

.

Perhaps a year, at most

.

Mr. Wentworth’s weary gaze staring out from his portrait had made me think I might be better off if he were here, in the flesh. I thought his homecoming might serve to pacify his wife, turning her heart soft to everyone around her, including me.

This, along with the notion that he had even a passing interest in fortune tellers brought me hope. Mama had often told those who sought counsel with her that the very act of sitting at a mystic’s table made a person more susceptible to curses and spells. “Once you open yourself up to me, you open yourself up to everything,” she’d say, before offering to part, for a fair price, with the protective charm she was wearing around her neck. “It works against everything from hexes to the evil eye.” The top drawer of her dresser was filled with an endless supply of the charms, for just such opportunities.

I’d always thought it was a bit of humbuggery on Mama’s part, done to make an extra dime, but the growing number of bruises on my arms and face had me changing my mind. I hoped, if Mr. Wentworth was a believer in things mystical and strange, that I could practise a bit of Mama’s magic to lure him home sooner rather than later. Cutting wishing dolls out of Mr. Wentworth’s stationery, I prayed Mama was right.

Late mornings Mrs. Wentworth would nearly wear out the carpet in the sitting room waiting for the post to arrive. No letters from Mr. Wentworth had come for her in all the time I’d been there, and according to Nestor, his last correspondence had left her in such a state that “we should be glad there has been nothing more.”

Nestor came to the door of the sitting room every morning at half past ten to deliver the post. Mrs. Wentworth would sort through the cards and letters one by one, anxiously searching for any word from her husband. She’d throw aside the notices of appreciation from various shopkeepers (Mr.

Macy looks forward to your return, Mr. A.T. Stewart is happy to meet all your needs, Mr. Tiffany knows your heart’s desire

) and file away any invitations for the upcoming season (the

pleasure of your company is requested on …, a dinner is being held in honour of …, nuptials will be celebrated for …

) all the while growing more and more agitated.

Two weeks after I’d fashioned my wish with paper and scissors, an envelope arrived bearing the familiar

W

of Mr. Wentworth’s stationery. Mrs. Wentworth turned it over several times before taking up her letter opener to slice along the edge of its flap. Her eyes widened as she unfolded the single page that was nestled inside. She read the message, mouthing the words. When she’d finished, she held the letter to her breast, then tucked it away in the top drawer of her desk.

“Two weeks, and he’ll be home,” she said, smiling.

I smiled as well, thinking there must be something to Mama’s magic after all.

Mrs. Wentworth began at once to make plans so that everything might be perfect for her husband’s return. Flowers were to be ordered, menus prepared, rooms that had been closed for months aired out and set right. “Where did you get that brandy you were so fond of last Christmas?” she asked her husband’s portrait, her brow pinched with not remembering.

Refusing to take lunch, she stayed at her desk and penned dozens of notes—orders to be carried out within the fortnight. When the clock chimed three, I thought she would decline her afternoon walk as well, but she turned to me (as she always did) and declared, “It’s time for promenade, Miss Fenwick.”

Mrs. Wentworth’s daily promenade was, of course, confined to the corridors of the house. I was to dress her in the appropriate attire at promptly three o’clock, and then, with parasol in hand and reticule dangling from her wrist, she would commence to walk.

It seemed altogether pointless to me, but Mrs. Wentworth took the ritual seriously, even going so far as to pause every few steps to look through the ceiling at the blue of an imagined sky, or to gaze past the walls into the shop windows of her memory. I followed her, pacing the hallways and up and down the stairs, taking the same tired path every day.

In appropriate weather, the proper ladies of New York engage in the tradition of taking an afternoon promenade. This, I can assure you, is quite a sight. In fine walking suits and feather-laden hats, they parade along Lady’s Mile at the prescribed orchestral gait of seventy-six beats per minute. Always andante, never allegretto. The purpose of this activity is not (as some may purport) to rejuvenate a lady’s constitution, but rather to allow her to practise setting her sights on the triumphs and inadequacies of others with discretion and ease.

At the end of the main floor hall was an enormous mirror. It spanned floor to ceiling, its gilded frame a gaudy tribute to turtledoves and fruit. Mrs. Wentworth took great care to watch herself as she approached the glass, straightening her shoulders, adjusting the angle of her parasol, raising her chin a bit in order to make a good impression on her own reflection. The day she received Mr. Wentworth’s letter, she went right up to the mirror until her nose touched the surface. When her short, laced-up breaths began to leave a foggy circle, she took a step back and resumed appraising herself. “My hem,” she said, looking down, motioning for me to fix a slight wrinkle in her skirt.

After seeing to the turn in the fabric, I got back to my feet and caught sight of myself in the mirror. My cheeks were covered with bruises, the skin around my eyes gone dark. The girl who’d peeped through the windows along Second Avenue, who’d longed to lie on her belly on an oriental rug, who’d wanted just one wink from the man with the big cigar, who’d dreamed of fine silk dresses and of lolling in Miss Keteltas’ soft feather bed, had all but disappeared.

Reaching out, Mrs. Wentworth stroked the top of my head. She ran her hand down the length of my braid, her fingers softly tugging it, counting each twist under her breath as she went. “… five for silver, six for gold, seven for a secret.”

I pulled away, unable, for once, to bear her touch.

“Get back here,” she scolded, reaching again for my hair and yanking my braid. “You’ll move when I tell you to move.”

“Please let me go,” I begged.

Dropping her parasol to the floor, she took my arm in her other hand and forced me to the sitting room.

“It’s for your own good,” she told me as she took a pair of scissors from her desk and minced the blades together in front of my face. “He would have favoured you too much. No matter how many bruises I give you, I can’t stop your beauty from coming back. I swear it mends in your sleep just to torment me.”

Day by day she’d been moving towards madness. Now, it seemed, she had arrived.

Holding me tight, she sawed at my braid. “I don’t know how to manage it any other way. It’s not your fault, of course, dear girl. You’ve been the most loyal of all—”

“Don’t,” I cried. I put my hand up to try to stop her, and she stabbed my fingers with the sharp scissors, turning my hand into a throbbing, bloody mess.

“Be sweet for me, Miss Fenwick,” she cooed then, as if what she’d done hadn’t hurt me in the least. “Let me finish. Let me keep my husband.”

Soon she held the length of my hair in her hand like a prize. The ribbon I’d tied to the end of my braid that morning dangled, looking worn and shabby against the perfect folds of her dress.

Cradling my hand in the front of my skirt, I bowed my head, dizzy and sick with pain. Crimson drops spilled to the floor, a pale, yellow flower in the carpet now ruined with my blood.

Mrs. Wentworth looked first to her husband’s portrait and then to me. “He can’t be trusted,” she said, her voice shaking. Then she went to the servant’s bell and rang it over and over again, crying out, “Nestor! Nestor, come quick! I need you!”

Please, Nestor, come

.

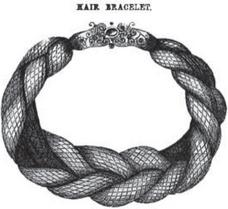

Sort the tress, which is about to be used, into lengths, tie ends firmly and quite straight with pack thread, put the hair into a small saucepan with about a pint and a half of water and a piece of soda the size of a nut, and boil it for about a quarter of an hour to twenty minutes; take it out, shake off the superfluous moisture and hang it up to dry, but not near a fire.

—from “How to Prepare Hair for Jewellery

Work,”

Godey’s Lady’s Book

, 1850

“N

ever let a stranger get hold of your hair,” Mama would scold as she’d gather up the strands that had fallen from my brush. “Powerful magic can be done against you by the person who finds it.” After collecting it all, she’d roll the hair between her palms and form it into a ratty-looking ball. Then she’d tuck the thing into the little cloth pouch she used for a hair receiver. She’d fashioned the pouch from one of my father’s handkerchiefs, sewing the square of cloth into a point and attaching a length of ribbon to the corners so she could hang it from a nail over the head of the bed.

“Remember Mrs. Deery?”

“Yes, Mama, I remember.”

“Remember what happened?”

“Yes, Mama.”

Mrs. Deery was dead. Mama said it was because the woman’s sister got angry with her, stole her hair and gave it to a bird. The bird flew off to a hole under the roof and then set about weaving Mrs. Deery’s hair into its nest. While the bird sewed the hair round and round, back and forth, between sticks and spiderwebs, Mrs. Deery fell into madness. She got so she couldn’t think straight anymore. She was sure that everyone was out to get her. She walked the streets, turning in circles and forgetting her name.

One day she spun herself right off the curb and was hit by a delivery wagon. There was nothing the driver could do. As barrels of fish tumbled off his cart, Mrs. Deery cried out from under the wheel, “She put a curse upon me! She wished for me to die …”

Whenever Mama’s receiver got too full, she’d take the hair and use it to fill her pincushion. It kept her needles and pins shiny and free from rust. When that hair got old, she’d take it out of the cushion, recite a charm over it and throw it into the fire.