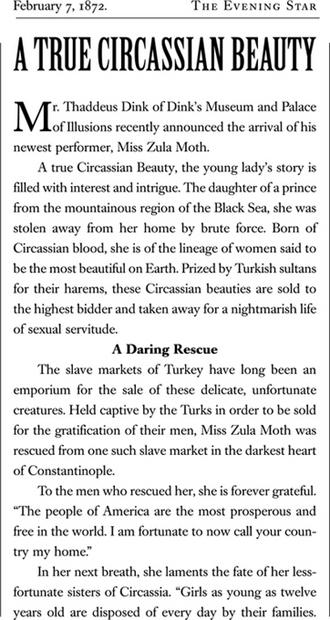

The Virgin Cure (45 page)

Ether is used by both physicians and photographers alike. Known for its sweet, medicinal scent, it can have an intoxicating effect when used in confined spaces.

At last, he walked away to fetch his weighty monster of a camera. Slipping underneath a long black cloak, he looked like he was attached to the thing, his legs set wide apart, his head and torso replaced by a box with four eyes and a sliding glass-plate heart.

He called to me, his voice muffled under the cloth. “I almost have you now. Five, four, three, two, one—think.” One hand reached out and took the cover away from the lenses.

I held as still as I could, searching for the answer to Mr. Sarony’s question. Memories came together in my mind and heart—Cadet kissing me, Dr. Sadie wiping away my tears, Mr. Dink stroking his beard, Mama holding her chin high as she tied her scarf around her head at the start of each day. Sitting there, with all the trappings of a life I’d never imagined, it came to me. No matter what the title read at the bottom of the card, or whatever name Mr. Dink might give me, I wanted the person holding it to see me—Moth, a girl from Chrystie Street.

EPILOGUE

I

live in a house on Gramercy Park with two pug dogs, a pair of lovebirds and an ever-changing cast of maids. Tomorrow I’ll turn nineteen.

Between a doctor’s garret and theatre lights I was raised to be a sideshow belle. Pretending came naturally to me. I’m my mother’s daughter after all.

Miss LeMar trained me in the ways of soothsayers, and was a far better fortune teller than Mama had ever been. Miss Eva refused to teach me to swallow swords, saying she didn’t want me to risk my beautiful throat. Shortly after I turned thirteen, Mr. Dink started a travelling circus. For six summers I boarded a train and journeyed to Cincinnati, Indianapolis, Chicago, St. Louis and all the towns between. Each September, tired of strangers, I came back to the city and embraced my dear New York.

The demand for Circassian Beauties waned over time, but fortunately people still continue to yearn for a glimpse of the future. These days I spend less time in the theatre and the museum and more hours in private consultation with Mrs. Astor’s four hundred. The ladies of society wish to know if they’ve made right choices—in evening gowns and china patterns, in friendships and in lovers. Their gentleman husbands, having held on during the dark years, want to know which stocks will rise and fall, which ventures will return high yields. The excitement of a lucky guess has caused me to fall into the arms of a banker, and a broker or two, but these transgressions were by choice and delicate negotiation, not for my survival.

Miss Everett goes on the same as always; she’s as much an institution in this town as Wall Street or the Metropolitan Bank.

Dr. Sadie goes on as well, now married to Mr. Hetherington and living in New Jersey, her spirit renewed by the birth of their first child, a little girl. She holds meetings of the SPCC in her home, her babe in her arms, telling other mothers of the darkness she’s seen. I go as myself, modestly dressed, my hair pulled back, and tell them my share of the story. When the women ask what they can do, I tell them, “Teach your children to be honest; teach your daughters to be strong.”

There is a new time ahead

, Dr. Sadie says. I hope that she is right.

I write these things from my sitting room, a place with a window so wide I can nearly see the whole of the park below. It’s surrounded by a tall iron fence to which only a chosen few hold the key. I wear mine on a chain around my neck, dangling down my back like a true Gypsy girl.

Walking the perimeter of the park every day, I look for a weakness, a space wide enough for a child to crawl through. So far, it has not appeared. I prefer to promenade on the outside of the gardens because I find it hard to sit inside the park. The walkways are perfect, every shrub, flower and bench beautiful and right. Even the houses the gardener built for the birds are palaces of safety and shelter. But shutting the gate doesn’t suit me. The moment it clangs, I’m left wishing I could leave it open as an invitation to some poor child walking by, the ghost of my younger self.

Requiring a lady’s maid, I opened my door to a girl six months ago, hoping to find such a ghost. Miss Maggie Harlow came to me from Forsyth Street, just steps away from where I once lived with Mama. She is a child with spirit, and eyes shining with pride.

In the afternoons we wander Broadway and Sixth Avenue along with all the other ladies of the mile. From Stewart’s to Stern’s we promenade with purpose, the city pulsing with our stride. At Tiffany’s on Union Square we stop to sift through jewels and gems, looking for the perfect stones to match our eyes. Every clerk and shopkeeper is happy to see us, knowing that our dreams, our wishes, our secrets are what hold up the buildings that now fill Manhattan’s sky.

As I close the pages on this tale, it is summer. Shoots are coming up from the stump of my father’s pear tree—I saw them only yesterday. Mr. Hetherington says that it happens every year: the tree tries hard to come back before Mr. Huber, in a rare appearance, comes to cut down its tender growth. One of these years Mr. Huber won’t come, and the tree will make a defiant return.

Miss Harlow went about the duty of dressing me this morning, but she has since gone to the train station with my best wishes and a hundred-dollar bill. A wonderful child with ambition enough to take her anywhere she wishes to go, I hadn’t the heart to hold her back. I filled her pockets with money and set her free.

She is steaming towards California to find her way.

I must find another girl.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

It started with an old painting, a long lost relative, and a little girl who once lived on the streets of New York.

When I was young, I used to sit and stare at a portrait that was hanging above our piano, a beautiful painting of a woman and a young girl. The woman, dressed in black taffeta, was seated in profile as she watched over the little girl who was at her knee. The child, looking as if she’d been allowed to play dress-up in her mother’s clothes, stared out of the painting with contentment, a loose fitting dressing gown the same shade of blue as the sky in the artist’s background draped around her, a large silver bracelet on her wrist. Her dark hair was held away from her face with a red ribbon, and I’d often beg my mother to fix my hair the same way. Every time I asked her to tell me about the two sitters in the portrait, she’d patiently explain, “The woman is your great-great-grandmother. I was named after her, and she was a lady doctor. The child is her daughter.”

My desire to learn more about “Dr. Sadie” followed me throughout my life. I begged all the information I could from my grandmother and other relatives, but family papers, journals and letters had been lost over the years, leaving me with little more than a few names and dates. In 2007, my mother passed away after a long battle with colorectal cancer. In the months that followed, I decided that it was time to uncover Sadie’s past for myself. I went back to notes I had taken several years before and began to piece her life together, one clue at a time.

It was a journey filled with serendipitous twists and turns. An envelope given to me by a medical historian led me to a woman who held a personal archive of letters written to and received from a young female medical student who happened to be a contemporary of my great-great-grandmother’s. Second-hand books as well as books and ephemera from the shelves of the New-York Historical Society Museum & Library helped me to understand what the city was like in the late 1800s (

The Nether Side of New York: Or, the Vice, Crime and Poverty of the Great Metropolis; Sunshine and Shadow in New York; Darkness and Daylight in New York: Or, Lights and Shadows of New York Life; a pictorial record of personal experiences by day and night in the great metropolis

, a “gentleman’s directory,” and a catalogue of exhibits at an anatomical museum, to name but a few.) Another trip led me to Dr. Steven G. Friedman of the New York Downtown Hospital, which celebrated its 150th anniversary in 2007. In his office I held in my hand an official historical document naming my great-great-grandmother as one of the first graduates of the Women’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children. I realized then that I had stumbled on a tale much larger than the one I had first set out to uncover, a tale that needed to be told.

In 1870, over thirty thousand children lived on the streets of New York City and many more wandered in and out of cellars and tenements as their families struggled to scrape together enough income to put food on the table.

Under the mentorship of sister physicians Drs. Elizabeth and Emily Blackwell, Sadie and her classmates worked tirelessly to care for such children. They faced fierce opposition from the medical establishment as well as from society. People sometimes rioted outside the doors of the infirmary, and funding was difficult to obtain. It was their mission to give health care to all women and children, no matter what their station or income might be. As the population of the city rose at an unprecedented rate, the ravages of disease were felt most keenly on the Lower East Side. Outbreaks of typhoid, diphtheria and smallpox rose alongside the continuous spread of tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases such as gonorrhea and syphilis. As the “lady doctors” of the infirmary worked to increase awareness of the plight of the city’s poor, the young boys of the tenements were shoved out the door to find work, and little girls became a commodity.