The War Between the Tates: A Novel (49 page)

Catching sight of Brian, whom she has not seen in nearly two weeks, Wendy waves and smiles—but not defiantly, or apologetically, or even consciously. It is, he thinks, exactly the smile and wave she would have given him if they had known each other only as professor and graduate student. The past is irrelevant, that smile announces; Wendy is living, as Ralph puts it, completely in the Now.

Up the street, still out of Brian’s line of vision, more signs have appeared, which would please him less.

END THE WAR EAT AT ELAINE’S COUNTRY COOKING

DONT FIGHT IT FANTASTIC DISCOUNT SALE AT COLLEGETOWN RECORDS

NOEL LEE AND THE GNOMES

IN CONCERT

MAY 15 NORTON HALL

Several other local enterprises have seized this chance for free publicity, and there are also a number of political placards, some local and regional

(GEORGE BRAMPTON FOR SCHOOL BOARD; VOTE NO ON SALES TAX),

others national or international

(BOYCOTT GRAPES; GIVE TO

INDIAN RELIEF).

Farther uphill in Collegetown, the Peace March is beginning to split into dissident and incongruous factions, physically suggesting to onlookers just the conclusion that Brian has worked so hard to avoid: that respectable liberal antiwar protest is dangerous because it brings in its train freakish, violent, and, socially disruptive elements. Art students are popping and releasing balloons; the Footlight Players, a local drama group, is holding up the procession with impromptu guerrilla theater. Two young women in the WHEN contingent, just ahead of Erica, have raised signs reading

NIXON IS A MALE CHAUVINIST WARHOG

and

STOP MEN KILLING

WOMEN AND CHILDREN.

Not far behind them, the Gay Liberation Center, which was not invited to join the march, has turned up anyhow with exceptionally colorful costumes and a large spangled banner:

MAKE LOVE, NOT WAR

GAY POWER FOR PEACE

Finally, at the rear of the procession, a large group of Maoists, also purposely uninvited by Brian, has appeared. Dressed in overalls, discarded army uniforms and assorted rags, wild-haired and wild-eyed, they carry homemade red flags of various shades from vermilion to dirty maroon. They are marching in unison, though not in rank, and chanting loudly as they pass through the campus gates into Collegetown:

“Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh!

NLF is going to win!”

In a few moments, as they pass a bar called the Old Bavaria, all hell is going to break loose. Empty beer bottles and other garbage will be thrown, fistfights will break out; there will be the sound of smashing plate glass, popping flashbulbs and police sirens.

Brian does not suspect any of this yet. He is imagining another event which lies ahead; his lunch with Erica. He recognizes her invitation as a favorable sign; if he puts it right, Erica will probably agree that he should move back home. After all, there are good reasons for this move: it will be much better for the children psychologically, and better for all of them economically and also socially. The Tates’ marital conflicts and related events have caused a lot of gossip and unfavorable comment. Now that things are quieter, he and Erica can close ranks and present a united front.

Most important, it is what they both want and need. The conflict has damaged them morally as well as in reputation: they have both said cruel things and made bad errors in judgment. They will each have to admit this, without accusing the other. Brian, for instance, must be generous enough not to point out that all that has happened is in a way Erica’s fault, since if she hadn’t insisted he leave home and marry Wendy, the affair would have ended much sooner, and he wouldn’t have become involved with hysterical feminists. Erica, in return, will be generous to him.

They will talk for a long while after lunch, Brian imagines. Moving into the sitting room—Erica curled on the blue sofa as usual, and he in his wing chair—they will relate and explain all that has passed. They will laugh, and possibly at some moments cry. They will encourage each other, console each other, and forgive each other. Finally, as the afternoon lengthens and the shadows of half-fledged trees reach toward the house, they will put their arms about each other and forget for a few moments that they were once exceptionally handsome, intelligent, righteous and successful young people; they will forget that they are ugly, foolish, guilty and dying.

More and more marchers are crowding into the park now. A group of mothers and small children has just come up to the fountain. One young woman leans over the basin beside Brian to wet a folded diaper and wipe the red-stained sticky face of a toddler in a stroller, while a boy just slightly older jerks the sleeve of her sweater to get her attention.

“Mommy?” he asks. “Mommy, will the war end now?”

“The author gratefully acknowledges the support given by the Creative Artists Public Service Programs (CAPS) during the writing of this book.”

Alison Lurie (b. 1926) is a Pulitzer Prize–winning author of fiction and nonfiction. Born in Chicago and raised in White Plains, New York, she grew up in a family of storytellers. Her father was a sociology professor and later the head of a social work agency; her mother was a former journalist. Lurie graduated from Radcliffe College, and in 1969 joined the English department at Cornell University, where she taught courses on children’s literature, among others.

Lurie’s first novel,

Love and Friendship

(1962), is a story of romance and deception among the faculty of a snowbound New England college. It won favorable reviews and established her as a keen observer of love in academia. Her next novel,

The Nowhere City

(1965), records the confused adventures of a young New England couple in Los Angeles among Hollywood starlets and Venice Beach hippies. She followed this with

Imaginary Friends

(1967), which focuses on a group of small-town spiritualists who believe they are in touch with extraterrestrial beings.

Her next novel,

Real People

(1969), led the

New York Times

to call her “one of our most talented and intelligent novelists.” The tale unfolds in a famous artists’ colony where much more than writing and painting occurs. Lurie then returned to an academic setting with her bestseller

The War Between the Tates

(1974), and drew on her own childhood in

Only Children

(1979). Four years later she published

Foreign Affairs

, her best-known novel, which traces the erotic entanglements of two American professors in England. It won the Pulitzer Prize in 1985.

The Truth About Lorin Jones

(1988) follows a biographer around the United States as she searches for the real, and sometimes shocking, story of a famous woman painter—a character who appears as an eight-year-old in

Only Children. The Last Resort

(1999) takes place in Key West, Florida, among a group of ill-assorted characters, some of who appear in earlier Lurie novels.

Truth and Consequences

(2005) returns to an academic setting and plumbs the troubles of a professor with back trouble, his exhausted wife, and two poets—one famous and one not.

Lurie has also published a collection of semi-supernatural stories,

Women and Ghosts

(1994), and a memoir of the poet James Merrill,

Familiar Spirits

(2001). Her interest in children’s literature inspired three collections of folktales, including

Clever Gretchen

(1980), which features little-known stories with strong female heroines. She has published two nonfiction books on children’s literature, as well:

Don’t Tell the Grown-ups

(1990) and

Boys and Girls Forever

(2003). In the lavishly illustrated

The Language of Clothes

(1981), she offers a lighthearted study of the semiotics of dress.

Lurie officially retired from Cornell in 1998, but continues to teach and write. In 2012 she was named to a two-year term as the official New York State Author. She lives in Ithaca, New York, and is married to the writer Edward Hower. She has three grown sons and three grandchildren.

Lurie at age seven.

Lurie at age fourteen, wearing her first long party dress in preparation for dancing school.

Lurie and her dog, Sliver, in the backyard of her family’s home in White Plains, New York, in the summer of 1947. (Photo courtesy of Kroch Library.)

Lurie on the porch of her parents’ home in White Plains, New York, in the early spring of 1947.

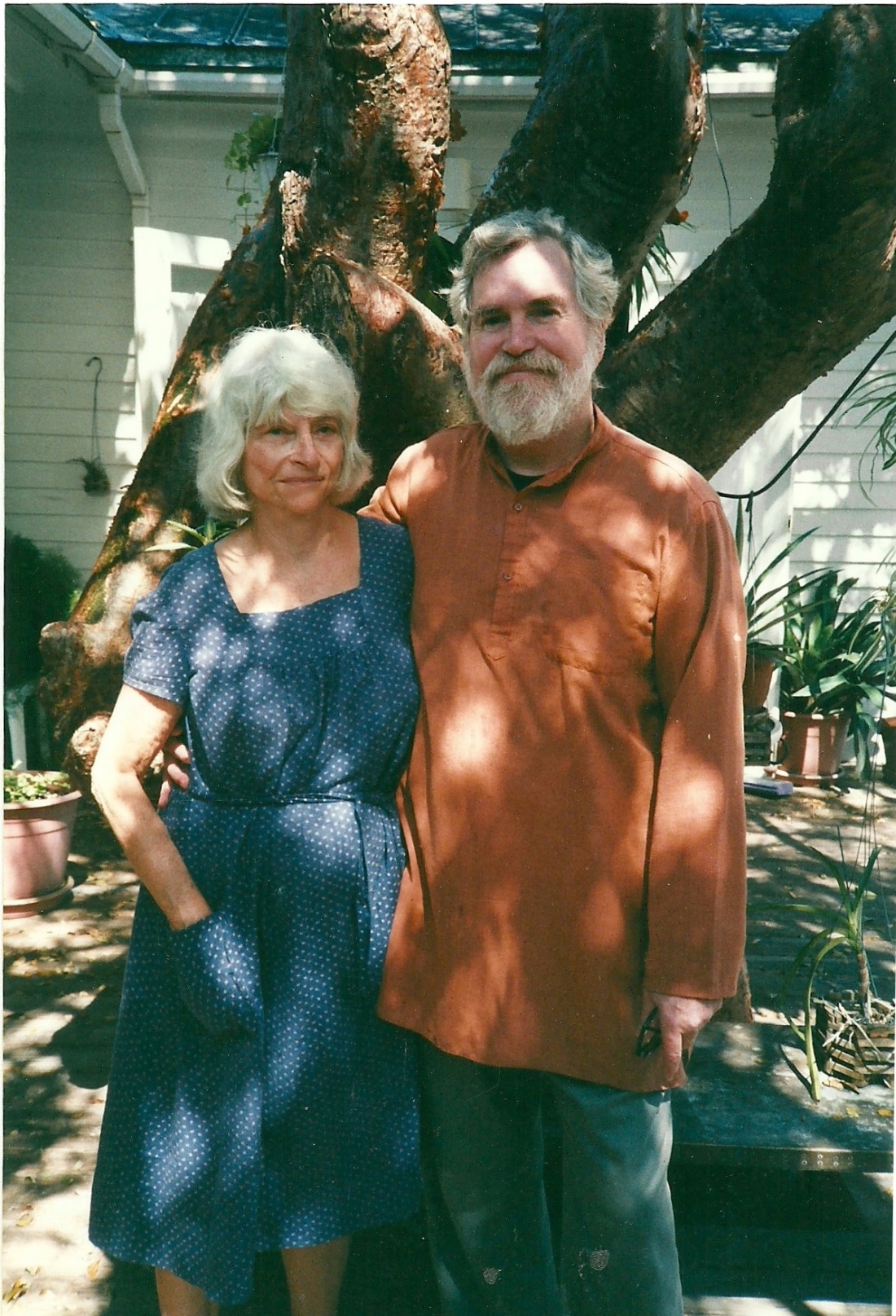

Lurie with her husband, Edward Hower, in Key West, Florida, in 2008.