The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (67 page)

Read The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 Online

Authors: Margaret MacMillan

Tags: #Political Science, #International Relations, #General, #History, #Military, #World War I, #Europe, #Western

The British military tended to assume that France would inevitably be defeated without support from Britain.

85

In 1912, Maurice Hankey, the Secretary to the Committee of Imperial Defence, the body responsible for British strategy, expressed a fairly common view of the French: ‘They don’t strike me as a really sound people.’ They had, said Hankey, bad sanitation, poor water, and slow railways. ‘I suspect’, he went on, ‘that the Germans could “beat them to a frazzle” any day.’

86

By the summer of 1911, the British military were thinking in terms of sending six infantry divisions and two brigades of cavalry to France, a total of 150,000 men and 67,000 horses. If the French assumptions about the number of men that Germany would use on the Western Front were correct, a British expeditionary force would tip the balance in favour of the Entente there.

87

While the army was making plans, the British navy was not, or if it was, Fisher and his successor, Sir Arthur Wilson, were not sharing their thinking with anyone, especially with the army which they saw as a competitor for funds. They strenuously opposed the idea of a British expeditionary force as expensive and useless. The navy was the key service, responsible, as it had always been, for defending the home islands, protecting British commerce on the high seas, and carrying war to the enemy through blockading its ports and possibly making amphibious landings. The army could play a role here, Fisher allowed in words he borrowed from Grey, ‘as a projectile to be fired by the Navy’.

88

Fisher in 1909 seems to have been thinking of series of small attacks on Germany’s coasts; ‘a mere fleabite! but a collection of these fleabites would make Wilhelm scratch himself with fury!’

89

Although Fisher was open-minded when it came to new technology – he leaned increasingly to fast cruisers rather than dreadnoughts and advocated using torpedoes and submarines to keep the German fleet penned up – he was not good at making strategic plans. When he was in office the first time, the navy did almost no planning; he was fond of saying that its chief war

plan was locked away in his brain where it would stay for greater security.

90

‘The vaguest amateur stuff I have ever seen,’ said a young captain of the Admiralty’s war plans during Fisher’s first period of tenure. He blamed Fisher himself, who generalised about war – ‘the enemy is to be hit hard & often, and many other aphorisms’ – but who never got down to solid detail.

91

For much of the prewar period the two British services went their own way, making their own plans, and eyeing each other as dogs would fighting over a bone. In 1911, however, the second crisis over Morocco, which brought in its train the now seemingly inevitable war scare, forced a meeting of the Committee of Imperial Defence on 23 August 1911 to review the whole of British strategy. (This was the only time before 1914 that such a review took place.)

92

Asquith, the Prime Minister, took the chair and among the other politicians were Richard Haldane, the Secretary of State for War, Grey, and two new and rising young men, Lloyd George and Winston Churchill. Henry Wilson, the new Director of Military Operations represented the army, and Fisher’s successor, Arthur Wilson, the navy. The army’s Wilson gave a brilliant exposition of the situation on the Continent and outlined the purpose and plans for the expeditionary force. His naval namesake did an appalling job: he objected to the very idea of the army sending a force to the Continent and outlined instead a vague scheme for blockading Germany’s North Sea coast as well as swooping in from to time to time to carry out amphibious raids. It also became clear that the navy had little interest in transporting the expeditionary force to France or protecting its communications.

93

Asquith thought the whole performance ‘puerile’.

94

Shortly afterwards he brought in as First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, who promptly got rid of Arthur Wilson and also set up a naval staff to draw up war plans. Churchill threw his support behind a British expeditionary force too, and the navy started to work with the army.

95

In 1912 Alexandre Millerand, a former socialist who had moved sufficiently to the right to become Minister of War, said of the British army: ‘The machine is ready to go: will it be unleashed? Complete uncertainty.’

96

The French remained unsure of British intervention until the Great War started, though some of its leaders, both military and civilian, were more sanguine than Millerand. Paul Cambon, the

influential ambassador in London, took away from Grey’s repeated assurances of friendship, and the fact that he had authorised the military conversations, the conviction that the British saw the Entente as an alliance (although he was never to be quite sure what that implied).

97

In 1919 Joffre said: ‘Personally, I was convinced that they would come, but in the end there was no formal commitment on their part. There were only studies on embarking and debarking and on the positions that would be reserved for their troops.’

98

The French viewed the growing hostility between Britain and Germany with relief and argued that the traditional British policy of keeping a balance of power in Europe (which had operated against France in the Napoleonic Wars) would now come to its aid. The French leaders also grasped that the British, as Grey had also said repeatedly, would be affected when it came to making a decision about war by who was to blame.

99

It was in part for this reason that the French were so careful to respond to events in the summer of 1914 and not take any steps that could be construed as aggressive.

The French military were encouraged by the presence of Henry Wilson as Director of Military Operations after 1910. He was an imposing figure, well over six feet tall, with a face which resembled, said a fellow officer, a gargoyle.

100

(Someone once addressed a postcard ‘To the Ugliest Man in the British Army’ and it reached him without difficulty.)

101

Wilson was ‘selfish and cunning’, as another colleague put it, skilled at political intrigue and good at finding influential patrons. He came from a moderately well-to-do Anglo-Irish family (and the cause of the Protestants in Ireland was always important to him) but had been obliged to make his own way in the world. As his presentation to the Committee of Imperial Defence demonstrated, he was clever and persuasive. He was also energetic and strong willed and had very clear views on strategy. In a paper he wrote in 1911 which was endorsed by the general staff, he took the view: ‘we

must

join France’. Russia, he argued, was not going to be much help if Germany attacked France; what would save Europe from a French defeat and dominance by Germany was the rapid mobilisation and dispatch of a British expeditionary force.

102

When he took up his office, Wilson was determined to make sure this happened. ‘I am very dissatisfied with the state of affairs in every respect,’ he wrote in his diary. There were no proper plans for

deploying the British expeditionary force or the reserves: ‘A lot of time spent writing beautiful minutes. I’ll break all this if I can.’

103

He rapidly established very good relations with the French military, helped by the fact that he loved France and spoke fluent French. He and the commandant of the French Staff College, the deeply Catholic Colonel Ferdinand Foch (as the future Field Marshal then was), became firm friends. ‘What would you say,’ Wilson once asked Foch, ‘was the smallest British military force that would be of any practical assistance to you in the event of a contest such as the one we have been considering?’ Foch did not pause to reflect: ‘One single private soldier,’ he replied, ‘and we would take good care that he was killed.’

104

The French would do whatever it took to get Britain to commit itself. In 1909 they produced a carefully faked document, said to have been discovered when a French commercial traveller picked up the wrong bag on a train, which purported to show Germany’s invasion plans for Britain.

105

Wilson made frequent visits to France to exchange information about war plans and work out arrangements for co-operation. He bicycled many miles along France’s frontiers, studying fortifications and likely battle sites. In 1910, shortly after his appointment, he visited one of the bloodier battlefields from the Franco-Prussian War in the part of Lorraine that remained to France: ‘We paid my usual visit to the statue of “France”, looking as beautiful as ever, so I laid at her feet a small bit of map I have been carrying, showing the areas of concentration of the British forces on her territory.’

106

Like his French hosts, Wilson assumed that the German right wing would not be strong enough to move nearer the sea, west of the Meuse in Belgium; the British expeditionary force would take its place on the French left wing to anticipate what was expected to be the weaker part of the German attack. There was some talk that the British might go to Antwerp but Wilson and his colleagues agreed that they could afford to be flexible and decide once the British forces had landed.

The British may have kept flexibility in their military plans but in political terms they were increasingly hemmed in. The first Morocco crisis of 1905–6 brought much greater co-operation and understanding between Britain and France but it also brought greater obligations. The crisis served as well to draw the lines more sharply between the powers in Europe. With the signing of the Anglo-Russian Convention in 1907,

yet another line was drawn and another strand of obligations and expectations woven, this time between two former enemies. It was more difficult, too, to ignore public opinion. In both France and Germany, for example, important business interests as well as key figures such as the French ambassador in Germany, Jules Cambon, were in favour of better relations. In 1909 France and Germany reached an amicable agreement over Morocco. Nationalists in both countries made it impossible for their governments to move further and discuss improved economic relations.

107

Europe was not doomed to divide itself into two antipathetic power blocs, each with its war plans to the ready, but as yet more crises succeeded the first Moroccan one, it became more difficult to change the pattern.

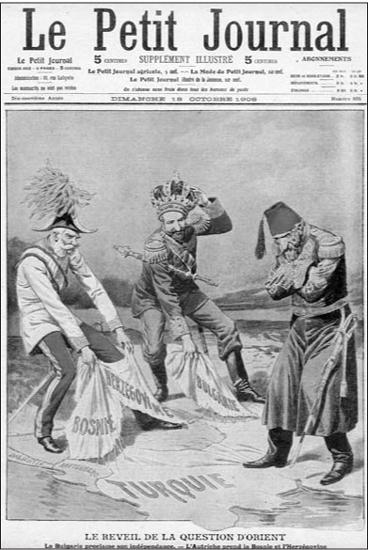

CHAPTER 14

The Bosnian Crisis: Confrontation between Russia and Austria-Hungary in the Balkans

In 1898, Kaiser Wilhelm II sailed on his yacht the

Hohenzollern

up the Dardanelles and into the Sea of Marmara to pay his second state visit to Abdul Hamid, the Ottoman sultan. Wilhelm liked to think of himself as the friend and protector of the Ottoman Empire. (He also had every intention of getting as many concessions as possible for Germany such as the right to build railways on Ottoman territory.) He was drawn too by the glamour of Constantinople itself. One of the greatest and most ancient cities in the world, Constantinople had seen many great rulers from Alexander the Great, to Emperor Constantine, and much more recently Suleiman the Magnificent. The scraps of Greek, Roman, and Byzantine columns and ornamentation which were embedded in its walls and foundations as much as its magnificent palaces, mosques and churches were reminders of the great empires which had come and gone.

The German royal couple were rowed ashore in a state caique and while the Kaiser rode around the great city walls on an Arab horse, the empress made an excursion to the Asian coast of the sea. That night the sultan gave his guests a lavish banquet in a new wing of his palace

which had been built expressly for the occasion. It was followed by a magnificent display of fireworks. Below in the harbour electric lights picked out the silhouettes of the German warships which had accompanied the Kaiser’s yacht. To mark his visit, the Kaiser presented the city with a large gazebo containing seven fountains, all made in Germany. With columns of porphyry, marble arches, a bronze dome decorated on the inside with gold mosaics and Wilhelm’s and Abdul Hamid’s initials carved into the stone, it still stands today at one end of the ancient Hippodrome where the Romans once raced their horses and chariots. For the sultan Wilhelm II had brought the latest German

rifle, but when he tried to present it Abdul Hamid at first shrank away in terror thinking he was about to be assassinated. The heir to Suleiman the Magnificent who had made Europe tremble nearly four centuries earlier was a miserable despot so fearful of plots that he kept a eunuch near him whose sole duty was to take the first puff on each of his cigarettes.