The War Within (3 page)

Authors: Bob Woodward

Tags: #History: American, #U.S. President, #Executive Branch, #Political Science, #Politics and government, #Iraq War; 2003, #Iraq War (2003-), #Government, #21st Century, #(George Walker);, #2001-2009, #Current Events, #United States - 21st Century, #U.S. Federal Government, #Bush; George W., #Military, #History, #1946-, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Political History, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Politics, #Government - Executive Branch, #United States

"I need to go meet this guy," Bush had told Hadley, "look him in the eye, make an assessment of him, but also make a commitment to him that I'm going to work with him and support him. He's never been the head of a country before.

He's going to have to learn. And I'm going to have to engage with him personally to help him learn. I can help him figure out how to be prime minister, because this guy has a lot of learning he's going to have to do."

And so they had planned the president's secret June 13 trip to Baghdad.

* * *

The president himself, despite his public statements, could see the war deteriorating. "If this is not working," Bush told Hadley, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and other close advisers in the spring and early summer of 2006,

"you people need to tell me. Because I cannot in good faith send more people who might die in Iraq unless it is working."

"I meet with families of the deceased," Bush said later. "I have got to be able to tell them, one, the mission is worthwhile, and we can succeed."

It clearly wasn't working. As a first step to find out why, Hadley had prepared an agenda for the president's meeting with his war cabinet the day before his trip to Baghdad, June 12, at Camp David. He wanted the group to evaluate the assumptions and ask the hard questionsó"the what, who, when, where and why," as he called it, of what they were doing.

The gathering was to be the curtain-raiser on a strategy review. The plan had been for the president to lead a conversation among his principalsóRice, Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld, Director of National Intelligence John D. Negroponte, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Peter Pace and Hadley. The SECRET agenda included big-picture questions, such as "What is fueling the current levels of violence?" Ninety minutes in the morning were to be devoted to "Examination of core issues and strategic assumptions" such as "Is our political strategy working?"

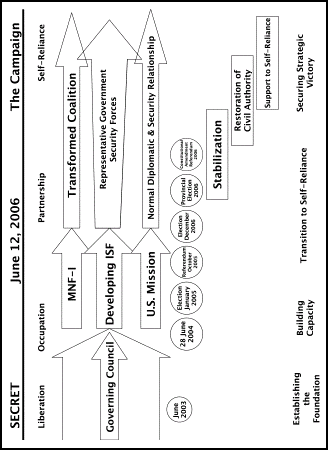

The morning had begun with a PowerPoint briefing on the campaign plan by General Casey from Baghdad, including this SECRET chartóa crazy quilt of circles, arrows, boxes and phrases with an undated end point called

"Securing strategic victory." (See opposite page.)

In addition to stating, "This strategy is shaped by a central tenet: Enduring, strategic success in Iraq will be achieved by Iraqis," Casey added, "Completion of political process and recent operations have positioned us for a decisive action over the next year."

He listed nine risks, ranging from a loss of willpower, to increasing sectarian violence, to rampant corruption, to a strategic surprise.

Rice's State Department briefing at Camp David that day asserted that the "situation in Iraq is not improving." It recommended that the administration "prepare [the] U.S. public for a long struggle," and said that changing the governing culture of Iraq would "require a generation."

But it turned out to be impossible to manage the Camp David event since the president had decided to go to Iraq the next day to see the new prime minister. The president's mind, Hadley could tell, was already halfway to Baghdad.

As so often happened, the daily tasks and the president's immediate focus had overtaken all else, and the process of strategic review was postponed yet again. As Iraq descended into unimaginable levels of violence, more and more American soldiers were dying under a strategy that Bush, Hadley and many of the others already knew was faltering.

* * *

Hadley stayed focused on the SECRET chart in his "GWB" file that showed the ever-increasing violence, a thousand attacks a weekósix an hour. "I'll believe we got it right in Iraq when that chart starts going down," he said.

* * *

Back in Washington, the president held a news conference in the Rose Garden the morning of June 14. He did not express any of the hesitation, concern or doubt about the strategy that he and Hadley and so many others in the administration had begun to share. Yes, he said, it was a tough war and there would never be zero violence. And yet,

"I sense something different happening in Iraq," he said. "The progress will be steady toward a goal that has been clearly defined."

* * *

Bush insisted he understood the nature of the war, whatever Casey might have thought. "I mean, of all people to understand that, it's me," he said.

But several of his on-the-record comments in the interview lend credence to Casey's concern that the president was overly focused on the number of enemy killed.

"What frustrated me is that from my perspective," the president said, "it looked like we were taking casualties without fighting back because our commanders are loath to talk about our battlefield victories."

Sure, periodically he had asked about how many enemy fighters had been eliminated. "That's one of many questions I asked. I asked that on occasion to find out whether or not we're fighting back. Because the perception is that our guys are dying and they're not. Because we don't put out numbers. We don't have a tally." He knew the military opposed body counts, which echoed the Vietnam-era practice of publishing the number of enemy killed as a measure of progress.

"On the other hand, if I'm sitting here watching the casualties come in, I'd at least like to know whether or not our soldiers are fighting," he said. "You've got a constant barrage of news basically saying, 'Lost three guys here. Five guys there. Seven guys lost.' You know, 'Twelve, twenty-eight for the week.'" The president simply wanted to know that the other side was suffering too.

So maybe Casey had hit upon a valid question. Did the commander in chief truly understand the war that he had started? Then again, did Casey himself understand the war? Did Rumsfeld? Or Rice? Or Hadley? Did anyone in the administration have a vision for how to succeed?

And most important, could anyone answer the president's own question, which loomed large and bright and inescapable:

"If it's not working, what do you do?"

Chapter 1 Two Years Earlier

O

ne weekday afternoon in May 2004, General George Casey bounded up the stairs to the third floor of his government-furnished quarters, a beautiful old brick mansion on the Potomac River at Fort McNair in Washington, D.C. His wife, Sheila, was packing for a move across the river to Fort Myer, in Virginia, the designated quarters of the Army's vice chief of staff.

"Please, sit down," Casey said.

In 34 years of marriage, he had never made such a request.

President Bush, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and the Army chief of staff had asked him to become the top U.S. commander in Iraq, he said.

Sheila Casey burst into tears. Like any military spouse, she dreaded the long absences and endless anxieties of separation, the strains of a marriage carried out half a world apart. But she also recognized it was an incredible opportunity for her husband. Casey saw the Iraq War as a pivot point, one of history's hinges, a conflict that would likely define America's future standing in the world, Bush's legacy and his own reputation as a general.

"This is going to be hard," Casey said, but he felt as qualified as anyone else.

Casey's climb to four-star status had been unusual. Instead of graduating from West Point, he had studied international relations at Georgetown University. He'd been there during the Vietnam War and was a member of ROTC, the Reserve Officers' Training Corps. He remembered how some students had spit on him and hurled things when he crossed campus in uniform. In 1970, after his graduation and commissioning as an Army second lieutenant, his father and namesake, a two-star Army general commanding the celebrated 1st Cavalry Division, was killed in Vietnam when his helicopter crashed en route to visit wounded soldiers.

Casey had never intended to make the Army his career. And yet he fell in love with the sense of total responsibility that even a young second lieutenant was given for the well-being of his men. Now, after 34 years in the Army, he was going to be the commander on the ground, as General William Westmoreland had been in Vietnam from 1965 to 1968. Casey had no intention of ending up like Westmoreland, whom history had judged as that era's poster boy for quagmire and failure.

Casey had never been in combat. His most relevant experience was in the BalkansóBosnia and Kosovoówhere irregular warfare had been the order of the day. He had held some of the most visible "thinker" positions in the Pentagonóhead of the Joint Staff strategic plans and policy directorate, J-5, and then the prestigious directorship of the Joint Staff, which served the chiefs. But aside from a 1981 stint in Cairo as a United Nations military observer, he had spent little time in the Middle East.

After getting Sheila's blessing, Casey met with Rumsfeld. The two sat at a small table in the center of the secretary's office. "Attitude" was important, Rumsfeld explainedóCasey must instill a frame of mind among the soldiers to let the Iraqis grow and do what they needed to do themselves. The general attitude in the U.S. military was "We can do this. Get out of our way. We'll take care of it. You guys stand over there." That would not spell success in Iraq, Rumsfeld explained. As he often would describe it later, the task in Iraq was to remove the training wheels and get American hands off the back of the Iraqi bicycle seat.

For the most part, Casey agreed.

"Take about 30 days, and then give me your assessment," Rumsfeld directed.

Casey was heartened that Rumsfeld and he shared a common vision. But he was surprised that the secretary of defense had devoted only about 10 minutes for a meeting with the man about to take over the most important assignment in the U.S. military.

The president held a small dinner at the White House for Casey and John Negroponte, the newly designated ambassador to Iraq, their spouses and a few friends. It was a social event, a way to say good luck.

* * *

Casey concluded that there was no clear direction on Iraq, so he invited Negroponte to his office at the Pentagon.

Negroponte, then the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, had volunteered for the Iraq ambassadorship. At 64, he was a 40-year veteran of the Foreign Service. He believed that an ambassador was the executor of policy made in Washington. He and Casey agreed that they weren't getting much guidance from above.

"What are we going to accomplish when we get over there?" Casey asked, and they started to hammer out a brief statement of purpose. The goal was a country at peace with its neighbors, with a representative government, which respected human rights for all Iraqis and would not become a safe haven for terrorists.

The general and the ambassador were pleased with their draft. They had laid out mostly political goals, despite the fact that the United States' main leverage was its nearly 150,000 troops on the ground.

* * *

Casey could relate. He was familiar with the deep, irrational hatred that had driven the ethnic cleansing and other violence in the Balkans.

He met with officers from the CIA station in Baghdad. They posed ominous questions: Could the whole enterprise work? What was the relationship between the political and military goals? Casey and Negroponte had settled on the political goals, but how would Casey achieve the military goal of keeping Iraq from becoming a safe haven for terrorists? As he was briefed and as he read the intelligence, he saw that terrorists had safe havens in at least four Iraq citiesóFallujah, Najaf, Samarra and, for all practical purposes, the Sadr City neighborhood in Baghdad.