The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination (18 page)

Read The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination Online

Authors: Ursula K. Le Guin

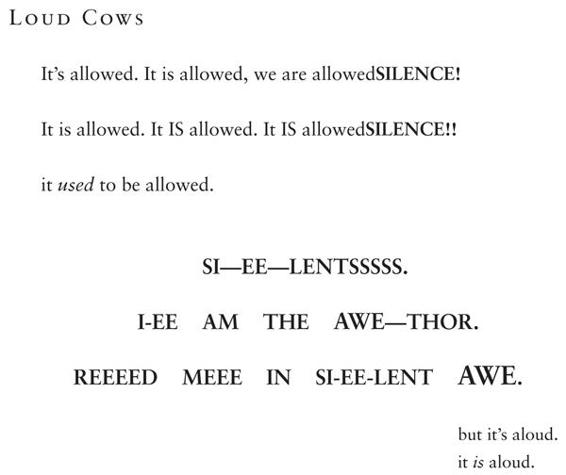

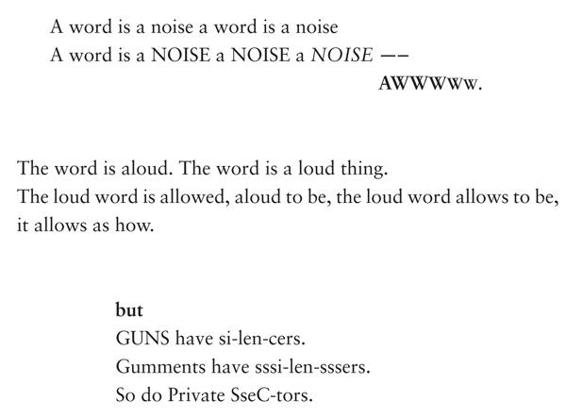

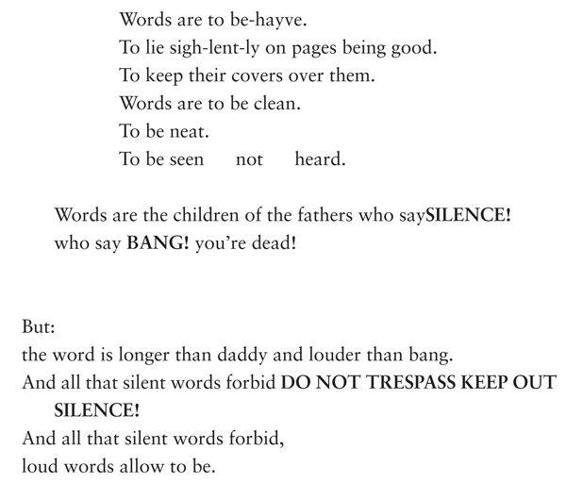

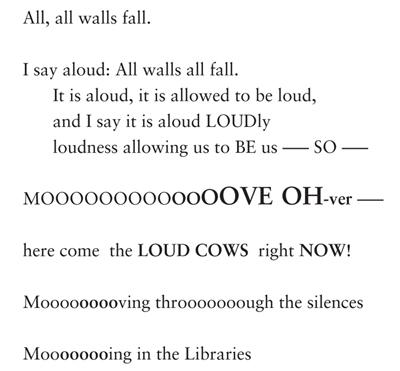

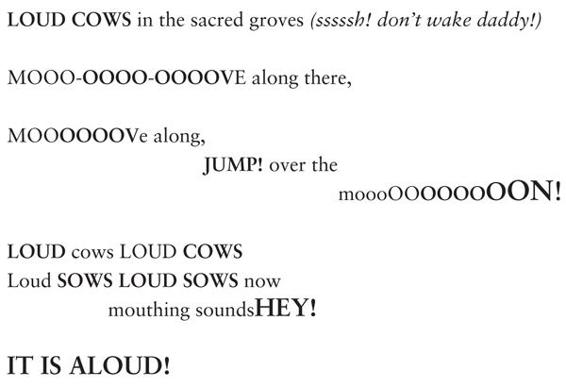

Well, when feminism got reborn, it urged literary women to raise their voices, to yell unladylikely, to shoot for parity. So ever since, we have been grabbing the mike and letting loose. And it was this spirit of

hey, let’s make a lot of noise

that carried me into experimenting with performance poetry. Not performance art, where you take your clothes off and dip yourself in chocolate or anything exciting like that, I’m way too old for that to work at all well and also I am a coward. But just letting my own voice loose, getting it off the page. Making female noises, shrieking and squeaking and being

shrill

, all those things that annoy people with longer vocal cords. Another case where the length of organs seems to be so important to men.

I read this piece, “Loud Cows,” on tape at first but then didn’t know what to do with the tape, so I do it live; and it’s never twice the same, and though it has been printed, it really needs you, the audience, to be there, going

eeso, eeso!

So I’ll end up now by performing it, in the hope of sending you away from this great conference with the memory of seeing an old woman mooing loudly in public.

In 1998 the editors of the interesting litcrit magazine

Paradoxa

asked me to contribute to an issue on “the future of narrative,” and this was the result. I have edited and fiddled with it here and there.

In earlier times, when we divided narrative into the secular and the sacred, factuality and invention were both considered to be properties of the former, and Truth the quality of the latter. With the decline of a consensus opinion concerning Truth, the difference between fact and fiction began to take on more importance, and we took to dividing narrative into fiction and nonfiction.

This division, maintained by publishers, librarians, booksellers, teachers, and most writers, I find to be fundamental to my own concept of narrative and its uses. The file in my computer that I’m using now is labelled “Nonfiction in Progress,” as distinct from the “Fiction in Progress” file. But, perhaps as part of the postmodern boundary breakdown, some files are coalescing; a lot of fiction seems to be getting into certain types of nonfiction. I like genre transgression, but this may involve more than genre. To start thinking about it, I called as usual on the OED.

F

ICTION

:

[1, 2—obsolete usages]

3.a. The action of ‘feigning’ or inventing imaginary incidents, existences, states of things, etc., whether for the purpose of deception or otherwise. [. . .] Bacon, 1605: “. . . so great an affinitie hath fiction and beleefe.” [. . .]

b. That which, or something that, is imaginatively invented; feigned existence, event, or state of things; invention as opposed to fact. [First citation 1398.]

4. The species of literature which is concerned with the narration of imaginary events and the portraiture of imaginary characters; fictitious composition. Now, usually, prose novels and stories collectively; the composition of works of this class. [First citation 1599.]

(Definitions 5 and after concern nonliterary and derogatory uses of the word—deliberate falsehood, moonshine, yarn spinning, and so on.)

As for the word

nonfiction

, it isn’t in the OED. Probably if I went to a contemporary American dictionary I’d find it, but not having one, and having found the thesaurus in my Macintosh a nice source of current usage, I asked it for its synonyms and antonyms to “fiction.” It gave me “story” as the principal synonym, then “unreality,” and then “drama, fantasy, myth, novel, romance, legend, tale.” All these synonyms except “unreality” have to do with the literary use of the word.

The principal antonym is “actuality,” then “authenticity, biography, certainty, circumstance, event, face [?], fact, genuineness, happening, history, incident, occurrence, reality.” Only two of the antonyms refer to literature: history and biography.

The antonyms didn’t include “nonfiction,” which I thought a quite common word by now. I tried the thesaurus with “nonfiction.” All it could give me was what it calls a Close Word—“fiction.”

Is my Macintosh telling me the words “fiction” and “nonfiction” are so close in meaning they can be used interchangeably?

Possibly this is what is happening.

A good deal has been said and written here and there about this blurring of definition or melding of modes, though I don’t know of a methodical or scholarly study. Most of what I’ve read on the subject has been by nonfiction writers defending their use of techniques and freedoms that have been seen as pertaining properly or only to fiction. Their arguments include the following: Since total accuracy is impossible, invention in a purportedly factual report is inevitable; since nobody perceives the same event the same way, factuality is always in question; artistic license may reach a higher form of authenticity than mere accuracy; and (therefore? anyhow?) writers have the right to write a story the way they want to.

The journalist Janet Malcolm, sued by her interviewee Jeffrey Masson for deliberate and defamatory misquotation, defended her form of journalism in a

New Yorker

article with such arguments. Perhaps she was inspired by Truman Capote, who called his

In Cold Blood

(also published in the

New Yorker

) a “nonfiction novel,” apparently to elevate it above mere reportage and incidentally defend himself from accusations of playing a bit fast and loose with facts. Some nonfiction writers vigorously defend their use of invented elements in their work. Others take it for granted and are surprised by objections.

In conversation, I have heard that “nature writing” often contains a good deal of invention, and that some well-known nature writers admit without shame to faking observations and relating experiences that didn’t occur. But the principal entryway of fiction into nonfiction seems to be via autobiographical writing—the memoir or “personal essay.” Two relevant quotes from reviewers (for which I thank Sara Jameson, who sent them to me): W. S. Di Piero, in the

New York Times Book Review

of March 8, 1998:

Remembering is an act of the imagination. Any account we make of our experience is an exercise in reinventing the self.

Even when we think we’re accurately reporting past events, persons, objects, places, and their sequence, we’re theatricalizing the self and its world.

I find the term “reinventing the self” interesting. Who did the original invention? Is the implication that of an eternal self-invention, the relationship of which to experience or reality is unimportant? The word “theatricalizing” is also interesting;

theatrical

isn’t a neutral word, but loaded with connotations of exaggeration and emotional falsehood.

In the same issue, Paul Levy wrote: “All autobiographers have a problem conjuring with the truth. My own strategy is to regard writing about oneself as inadvertent fiction.”

“Conjuring” has the same ring to it as “theatricalizing”—autobiography as sleight of hand, doves out of thin air. The phrase “inadvertent fiction” not only disclaims the writer’s responsibility, but offers irresponsibility as a strategy. This approach certainly could slide an autobiographer over the difficulties faced by writers unwilling to regard their art as inadvertent.

A related argument concerns objectivity, famed cornerstone of the scientific method, which many scientists now consider, as a realistic criterion of even the most painstakingly factual report of an experiment or observation, illusory. Feminists add that, as an ideal, it is in many ways undesirable.

Anthropologists have generally come to admit that accounts of ethnographical observations from which the observer is omitted contain a profound element of falsification. Ethnography these days is full of postmodern uncertainties, ellipses, and self-reflexivities, sometimes to the point of appearing to be less about the natives’ behavior than the ethnographer’s soul. Claude Lévi-Strauss’s

Tristes Tropiques

, the founding classic of this subtle and risky genre, exhibits its value when performed by a truly searching, skillful subjectivity.