The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination (26 page)

Read The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination Online

Authors: Ursula K. Le Guin

Having made this vast, rash statement, I thought I should try to see if it worked. I felt I should be scientific. I should do an experiment.

It is not very rash to say that in a sentence by Jane Austen there is a balanced rhythm characteristic of all good eighteenth-century narrative prose, and also a beat, a timing, characteristic of Jane Austen’s prose. Following what Woolf said about the rhythm of

Pointz Hall

, might one also find a delicate nuancing of the beat that is characteristic of

that particular

Jane Austen novel?

I took down my Complete Austen and, as in the

sortes Vergilianae

or a lazy consultation of the

I Ching

, I let the book open where it wanted. First in

Pride and Prejudice

, and copied out the first paragraph my eyes fell on. Then again in

Persuasion

.

From

Pride and Prejudice:

More than once did Elizabeth in her ramble within the Park, unexpectedly meet Mr Darcy.—She felt all the perverseness of the mischance that should bring him where no one else was brought: and to prevent its ever happening again, took care to inform him at first, that it was a favourite haunt of hers.—How it could occur a second time therefore was very odd!—Yet it did, and even a third.

From

Persuasion:

To hear them talking so much of Captain Wentworth, repeating his name so often, puzzling over past years, and at last ascertaining that it

might

, that it probably

would

, turn out to be the very same Captain Wentworth whom they recollected meeting, once or twice, after their coming back from Clifton:—a very fine young man: but they could not say whether it was seven or eight years ago,—was a new sort of trial to Anne’s nerves. She found, however, that it was one to which she must enure herself.

Probably I’m fooling myself, but I was quite amazed at the result of this tiny test.

Pride and Prejudice

is a brilliant comedy of youthful passions, while

Persuasion

is a quiet story about a misunderstanding that ruins a life and is set right only when it’s almost too late. One book is April, you might say, and the other November.

Well, the four sentences from

Pride and Prejudice

, separated rather dramatically by a period and a dash in each case, with a colon breaking the longest one in two, are all quite short, with a highly varied, rising rhythm, a kind of dancing gait, like a well-bred young horse longing to break out into a gallop. All are entirely from young Elizabeth’s point of view, in her own mental voice, which on this evidence is lively, ironical, and naive.

Though the paragraph from

Persuasion

is longer, it is in only two sentences; the long first one is full of hesitations and repetitions, marked by eight commas, two colons, and two dashes. Its abstract subject (“to hear them”) is separated from its verb (“was”) by several lines, all having to do with other people’s thoughts and notions. The protagonist of the sentence, Anne, is mentioned only in the next-to-last word. The sentence that follows, wholly in her own mental voice, has a brief, strong, quiet cadence.

I do not offer this little analysis and comparison as proof that any paragraph from

Pride and Prejudice

would have a different rhythm from any sentence in

Persuasion;

but as I said, it surprised me—the rhythms were in fact so different, and each was so very characteristic of the mood of the book and the nature of the central character.

But of course I am already persuaded that Woolf was right, that every novel has its characteristic rhythm. And that if the writer hasn’t listened for that rhythm and followed it, the sentences will be lame, the characters will be puppets, the story will be false. And that if the writer can hold to that rhythm, the book will have some beauty.

What the writer has to do is listen for that beat, hear it, keep to it, not let anything interfere with it. Then the reader will hear it too, and be carried by it.

A note on rhythms that I was aware of in writing two of my books:

Writing the fantasy novel

Tehanu

, I thought of the work as riding the dragon. In the first place, the story demanded that I be outdoors while writing it—which was lovely in Oregon in July, but inconvenient in November. Cold knees, wet notebook. And the story came not steadily, but in flights—durations of intense perception, sometimes tranquil and lyrical, sometimes frightening—which most often occurred while I was waking, early in the morning. There I would lie and ride the dragon. Then I had to get up, and go sit outdoors, and try to catch that flight in words. If I could hold to the rhythm of the dragon’s

flight, the very large, long wingbeat, then the story told itself, and the people breathed. When I lost the beat, I fell off, and had to wait around on the ground until the dragon picked me up again.

Waiting, of course, is a very large part of writing.

Writing “Hernes,” a novella about ordinary people on the Oregon coast, involved a lot of waiting. Weeks, months. I was listening for voices, the voices of four different women, whose lives overlapped throughout most of the twentieth century. Some of them spoke from a long time ago, before I was born, and I was determined not to patronise the past, not to take the voices of the dead from them by making them generalised, glib, quaint. Each woman had to speak straight from her center, truthfully, even if neither she nor I knew the truth. And each voice must speak in the cadence characteristic of that person, her own voice, and also in a rhythm that included the rhythms of the other voices, since they must relate to one another and form some kind of whole, some true shape, a story.

I had no dragon to carry me. I felt diffident and often foolish, listening, as I walked on the beach or sat in a silent house, for these soft imagined voices, trying to hear them, to catch the beat, the rhythm, that makes the story true and the words beautiful.

I do think novels are beautiful. To me a novel can be as beautiful as any symphony, as beautiful as the sea. As complete, true, real, large, complicated, confusing, deep, troubling, soul enlarging as the sea with its waves that break and tumble, its tides that rise and ebb.

An unpublished piece in which I return to and go on from some of the themes and speculations of the essay “Text, Silence, Performance” in my previous nonfiction collection

Dancing at the Edge of the World.

M

ODELS OF

C

OMMUNICATION

In this Age of Information and Age of Electronics, our ruling concept of communication is a mechanical model, which goes like this:

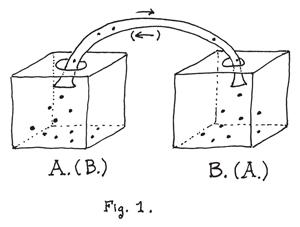

Box A and box B are connected by a tube. Box A contains a unit of information. Box A is the transmitter, the sender. The tube is how the information is transmitted—it is the medium. And box B is the

receiver. They can alternate roles. The sender, box A, codes the information in a way appropriate to the medium, in binary bits, or pixels, or words, or whatever, and transmits it via the medium to the receiver, box B, which receives and decodes it.

A and B can be thought of as machines, such as computers. They can also be thought of as minds. Or one can be a machine and the other a mind.

If A is a mind and B a computer, A may send B information, a message, via the medium of its program language: let’s say A sends the information that B is to shut down; B receives the information and shuts down. Or let’s say I send my computer a request for the date Easter falls on this year: this request requires the computer to respond, to take the role of box A, which sends that information, via its code and the medium of the monitor, to me, who now take the role of box B, the receiver. And so I go buy eggs, or don’t buy eggs, depending on the information I received.

This is supposed to be the way language works. A has a unit of information, codes it in words, and transmits to B, who receives it, decodes it, understands it, and acts on it.

Yes? This is how language works?

As you can see, this model of communication as applied to actual people talking and listening, or even to language written and read, is at best inadequate and most often inaccurate. We don’t work that way.

We only work that way when our communication is reduced to the most rudimentary information. “STOP THAT!” in a shout from A is likely to be received and acted on by B—at least for a moment.

If A shouts, “The British are coming!” the information may serve as information—a clear message with certain clear consequences concerning what to do next.

But what if the communication from A is, “I thought that dinner last night was pretty awful.”

Or, “Call me Ishmael.”

Or, “Coyote was going there.”

Are those statements information? The medium is the speaking voice, or the written word, but what is the code? What is A

saying?

B may or may not be able to decode, or “read,” those messages in a literal sense. But the meanings and implications and connotations they contain are so enormously complex and so utterly contingent that there is no one right way for B to decode or to understand them. Their meaning depends almost entirely on who A is, who B is, what their relationship is, what society they live in, their level of education, their relative status, and so on. They are full of meaning and of meanings, but they are not information.

In such cases, in most cases of people actually talking to one another, human communication cannot be reduced to information. The message not only involves, it

is

, a

relationship

between speaker and hearer. The medium in which the message is embedded is immensely complex, infinitely more than a code: it is a language, a function of a society, a culture, in which the language, the speaker, and the hearer are all embedded.

“Coyote was going there.” Is the information being transmitted by this sentence—does it “say”—that an actual coyote actually went somewhere? Actually, no. The speaker is not talking about a coyote. The hearer knows that.