The Wench is Dead (20 page)

Authors: Colin Dexter

‘Well, we don’t need a microscope to tell us it’s a cut: neat, clean, straight-forward

cut

, all right?’

‘With a knife?’

‘What the hell else do you cut things with?’

‘Cheese-slicer? Pair of—?’

‘What a wonderful thing, Morse, is the human imagination!’

It was a wonderful thing, too, that Morse had received such an unequivocal answer to one of his questions; the very first such answer, in fact, in their long and reasonably amicable

acquaintanceship.

HAPTER

T

HIRTY-FIVE

Heap not on this mound

Roses that she loved so well;

Why bewilder her with roses

That she cannot see or smell?

(

Edna St Vincent Millay

, Epitaph)

I

NSPECTOR

M

ULVANEY SPOTTED

him parking the car in the ‘Visitor’ space. When the little station had been converted

ten years earlier from a single detached house into Kilkearnan’s apology for a crime-prevention HQ, the Garda had deemed it appropriate that the four-man squad should be headed by an

inspector. It seemed, perhaps, in retrospect, something of an over-reaction. With its thousand or so inhabitants, Kilkearnan regularly saw its ration of fisticuffs and affray outside one or more of

the fourteen public-houses; but as yet the little community had steered clear of any involvement in international smuggling or industrial espionage. Here, even road accidents were a rarity –

though this was attributable more to the comparative scarcity of cars than to the sobriety of their drivers. Tourists there were, of course – especially in the summer months; but even they,

with their Rovers and BMWs, were more often stopping to photograph the occasional donkey than causing any hazard to the occasional drunkard.

The man parking his Lancia in the single (apart from his own) parking-space, Mulvaney knew to be the English policeman who had rung through the previous day to ask for help in locating a

cemetery (for, as yet, no stated purpose) and who thought it was probably the one overlooking Bertnaghboy Bay – that being the only burial ground marked on the local map. Mulvaney had been

able to assure Chief Inspector Morse (such was he) that indeed it would be the cemetery which lay on the side of a hill to the west of the small town: the local dead were always likely to be buried

there, as Mulvaney had maintained – there being no alternative accommodation.

From the lower window, Mulvaney watched Morse with some curiosity. It was not every day (or week, or month) that any contact was effected between the British Police and the Garda; and the man

who was walking round to the main (only) entrance looked an interesting specimen: mid-fifties, losing his whitish hair, putting on just a little too much weight, and exhibiting perhaps, as was to

be hoped, the tell-tale signs of liking his liquor more than a little. Nor was Mulvaney disappointed in the man who was shown into his main (only) office.

‘Are you related to Kipling’s Mulvaney?’ queried Morse.

‘No, sor! But that was a good question – and educashin, that’s a good thing, too!’

Morse explained his unlikely, ridiculous, selfish mission, and Mulvaney warmed to him immediately. No chance whatsoever, of course, of any exhumation order being granted, but perhaps Morse might

be interested in hearing about the business of grave digging in the Republic? A man could never

dig

a grave on a Monday, and that for perfectly valid reasons, which he had forgotten; and in

any case it wasn’t Monday, was it? And if a grave

was

dug, even on a Monday, it had always –

always

, sor! – to be in the morning, or at least the previous evening.

That was an important thing, too, about all the forks and shovels: placed across the open grave, they had to be, in the form of the holy cross, for reasons which a man of Morse’s educashin

would need no explanation, to be sure. Last, it was always the custom for the chief mourner to supply a little quantity of Irish whiskey at the graveside for the other members of the saddened

family; and for the grave-diggers, too, of course, who had shovelled up the clinging, cloggy soil. ‘For sure, ’tis always a t’irsty business, sor, that working of the

soil!’

So Morse, the chief mourner, walked out into the main (only) High Street, and purchased three bottles of Irish malt. An understanding had been arrived at, and Morse knew that whatever the

problems posed by the Donavan-Franks equation, the left-hand side would be solved (if solved it

could

be) with the full sympathy and (unofficial) co-operation of the Irish Garda.

In his mind’s eye, Morse had envisaged a bank of arc-lights, illuminating a well-marked grave, with barricades erected around the immediate area, a posse of constables to keep the public

from prying, and press photographers training their telescopic lenses on the site. The time? That would be 5.30 a.m. – the usual exhumation hour. And excitement would be intense.

It was not to be.

Together, Morse and Mulvaney had fairly easily located the final habitation of the greatest man in all the world. In all, there must have been about three or four hundred graves within the

walled area of the hillside cemetery. Half a dozen splendidly sculptured angels and madonnas kept watch here and there over a few former dignitaries, and several large Celtic crosses marked other

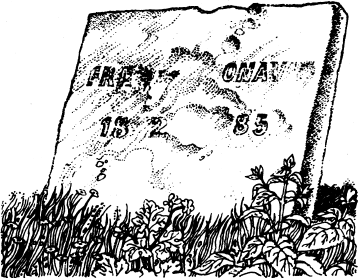

burial-plots. But the great majority of the dead lay unhonoured here beneath untended, meaner-looking memorials. Donavan’s stone was one of the latter, a poor, mossed-and-lichened thing, with

white and ochre blotches, and no more than two feet high, leaning back at an angle of about 20 degrees from the vertical. So effaced was the weathered stone that only the general outlines of the

lettering could be followed – and that only on either side of a central disintegration:

‘That’s him,’ said Morse triumphantly. It looked as if his name

had

been Frank.

‘God rest his soul!’ added Mulvaney. ‘ – that’s if it’s there, of course.’

Morse grinned, and wished he’d known Mulvaney long ago. ‘How are you going to explain …?’

‘We are digging yet another grave, sor. In the daylight – and just as normal.’

It was all quite quick. Mulvaney had bidden the two men appointed to the task to dig a clean rectangle to the east of the single stone; and after getting down only two or three feet, one of the

spades struck what sounded like, and was soon revealed to be, a wooden coffin. Once all the dark-looking earth had been removed and piled on each side of the oblong pit, Morse and Mulvaney looked

down to a plain coffin-top, with no plate of any sort screwed into it. The wood, one-inch elm-boarding, and grooved round the top, looked badly warped, but in a reasonable state. There seemed no

reason to remove the complete coffin; and Morse, betraying once again his inveterate horror of corpses, quietly declined the honour of removing the lid.

It was Mulvaney himself, awkwardly straddling the hole, his shoes caked with mud, who bent down and pulled at the top of the coffin, which gave way easily, the metal screws clearly having

disintegrated long ago. As the board slowly lifted, Mulvaney saw, as did Morse, that a whitish mould hung down from the inside of the coffin-lid; and in the coffin itself, covering the body, a

shroud or covering of some sort was overspread with the same creeping white fungus.

Round the sides at the bottom of the coffin, plain for all to see, was a bed of brownish, dampish sawdust, looking as fresh as if the body which lay on it had been buried only yesterday. But

what

body?

‘’Tis wonderfully well preserved, is it not, sor? ’Tis the peat in the soil that’s accountin’ forrit.’

This from the first grave-digger, who appeared more deeply impressed by the wondrous preservation of the wood than by the absence of any body.

For the coffin contained no body at all

.

What it did contain was a roll of carpet, of some greenish dye, about five feet in length, folded round what appeared to have been half a dozen spaded squares of peat. Of Donavan there was no trace

whatsoever – not even a torn fragment from the last handbill of the greatest man in all the world.

HAPTER

T

HIRTY-SIX

A man’s learning dies with him; even his virtues fade out of remembrance; but the dividends on the stocks he bequeaths may serve to keep his memory green

(

Oliver Wendell Holmes

, The Professor at the Breakfast Table)

M

ORSE GREW SOMEWHAT

fitter during the days following his return from Ireland; and very soon, in his own judgement at least, he had managed to regain

that semblance of salubrity and strength which his GP interpreted as health. Morse asked no more.

He had recently bought himself the old Furtwängler recording of

The Ring

; and during the hours of Elysian enjoyment which that performance was giving him, the case of Joanna Franks,

and the dubious circumstances of the Oxford Tow-path Mystery, assumed a slowly diminishing significance. The whole thing had brought him some recreative enjoyment, but now it was finished.

Ninety-five per cent certain (as he was) that the wrong people had been hanged in 1860, there was apparently nothing further he could do to dispel that worrying little five per cent of doubt.

Christmas was coming up fast, and he was glad not to have that tiring traipsing round the shops – no stockings, no scent to buy. He himself received half a dozen cards; two invitations to

Drinks Evenings; and a communication from the JR2:

XMAS PARTY

The Nursing Staff of the John Radcliffe

Hospital request the pleasure of your company

on the evening of Friday, 22nd December,

from 8p.m. until midnight,

at the Nurses’ Hostel, Headington Hill, Oxford.

Disco Dancing, Ravishing Refreshments, Fabulous fun!

Please Come! Dress informal. RSVP.

The printed card was signed, in blue biro, ‘Ward 7C’ – and followed by a single ‘X’.

It was on Friday, 15th December, a week before the scheduled party, that Morse’s eye caught the name in the

Oxford Times

‘Deaths’ column:

DENISTON, Margery – On December 10th, peacefully at her home in Woodstock, aged 78 years. She wished her body to be given to medical research. Donations gratefully

received, in honour of the late Colonel W. M. Deniston, by the British Legion Club, Lambourn.

Morse thought back to the only time he’d met the quaint old girl, so proud as she had been of her husband’s work – a work which had brought Morse such disproportionate

interest; a work which he’d not even had to pay for. He signed a cheque for £20, and stuck it in a cheap brown envelope. He had both first- and second-class stamps to hand, but he chose

a second-class: it wasn’t a matter of life and death, after all.

He would (he told himself) have attended a funeral service, if she’d been having one. But he was glad she wasn’t: the stern and daunting sentences from the Burial Service, especially

in the A.V., were ever assuming a nearer and more personal threat to his peace of mind; and for the present that was something he could well do without. He looked up the British Legion’s

Lambourn address in the telephone directory, and after doing so turned to ‘Deniston, W. M.’. There it was: 46 Church Walk, Woodstock. Had there been any family? It hardly appeared so,

from the obituary notice. So? So what happened to things, if there was no one to leave them to? As with Mrs Deniston, possibly? As with anyone childless or unmarried …

It was difficult parking the Lancia, and finally Morse took advantage of identifying himself to a sourpuss of a traffic warden who reluctantly sanctioned a temporary straddling

of the double-yellows twenty or so yards from the grey-stoned terraced house in Church Walk. He knocked on the front door, and was admitted forthwith.

Two persons were in the house: a young man in his middle twenties who (as he explained) had been commissioned by Blackwells to catalogue the few semi-valuable books on the late Denistons’

shelves; and a great-nephew of the old Colonel, the only surviving relative, who (as Morse interpreted matters) was in for a very pretty little inheritance indeed, if recent prices for Woodstock

property were anything to judge by.

To the latter, Morse immediately and openly explained what his interest was: he was begging nothing – apart from the opportunity to discover whether the late Colonel had left behind any

notes or documents relating to

Murder on the Oxford Canal

. And happily the answer was ‘yes’ – albeit a very limited ‘yes’. In the study was a pile of

manuscript, and typescript, and clipped to an early page of the manuscript was one short letter – a letter with no date, no sender’s address, and no envelope:

Our dear Daniel,

We do both trust you are keeping well these past months. We shall be in Derby in early Sept. when we hope we shall be with you. Please say to Mary how the dress she did was very successfull

and will she go on with the other one if she is feeling recovered.

Yours Truely and Afectionatly,

Matthew