The Wench is Dead (22 page)

Authors: Colin Dexter

Just like the Oxford-City-Council Vandals when …

Forget it, Morse!

‘Where to now, sir?’

It took a bit of saying, but he said it: ‘Straight home, I think. Unless there’s something else

you

want to see?’

HAPTER

T

HIRTY-NINE

And what you thought you came for

Is only a shell, a husk of meaning From which the purpose breaks only when it is fulfilled

If at all. Either you had no purpose

Or the purpose is beyond the end you figured

And is altered in fulfilment

(

T. S. Eliot

, Little Gidding)

M

ORSE SELDOM ENGAGED

in any conversation in a car, and he was predictably silent as Lewis drove the few miles out towards the motorway. In its wonted

manner, too, his brain was meshed into its complex mechanisms, where he was increasingly conscious of that one little irritant. It had always bothered him not to know, not to have heard –

even the smallest things:

‘What was it you were saying back there?’

‘You mean when you weren’t listening?’

‘Just

tell

me, Lewis!’

‘It was just when we were children, that’s all. We used to measure how tall we were getting. Mum always used to do it – every birthday – against the kitchen wall. I

suppose that’s what reminded me, really – looking in that kitchen. Not in the front room – that was the best wallpaper there; and, as I say, she used to put a ruler over the top

of our heads, you know, and then put a line and a date …’

Again, Morse was not listening.

‘Lewis! Turn round and go back!’

Lewis looked across at Morse with some puzzlement.

‘I said just turn round,’ continued Morse – quietly, for the moment. ‘

Gentle

as you like – when you get the

chance

, Lewis – no need to imperil

the pedestrians or the local pets. But just

turn round

!’

Morse’s finger on the kitchen switch produced only an empty ‘click’, in spite of what looked like a recent bulb in the fixture that hung, shadeless, from the

disintegrating plaster-boards. The yellowish, and further yellowing, paper had been peeled away from several sections of the wall in irregular gashes, and in the damp top-corner above the sink it

hung away in a great flap.

‘Whereabouts did you use to measure things, Lewis?’

‘’Bout here, sir.’ Lewis stood against the inner door of the kitchen, his back to the wall, where he placed his

left palm horizontally across the top of his head, before turning round and assessing the point at which his fingertips had marked the height.

‘Five-eleven, that is – unless I’ve shrunk a bit.’

The wallpaper at this point was grubby with a myriad fingerprints, appearing not to have been renovated for half a

century or more; and around the non-functioning light-switch the plaster had been knocked out, exposing some of the bricks in the partition-wall. Morse tore a strip from the yellow paper, to reveal

a surprisingly well-preserved, light-blue paper beneath. But marked memorials to Joanna, there were none; and the two men stood silent and still there, as the afternoon seemed to grow perceptibly

colder and darker by the minute.

‘It was a thought, though, wasn’t it?’ asked Morse.

‘Good thought, sir!’

‘Well, one thing’s certain! We are

not

going to stand here all afternoon in the gathering gloom and strip all these walls of generations of wallpaper.’

‘Wouldn’t take all that long, would it?’

‘What? All this bloody stuff—’

‘We’d know where to look.’

‘We would?’

‘I mean, it’s only a little house; and if we just looked along at some point, say, between four feet and five feet from the floor – downstairs only, I should

think—’

‘You’re a genius – did you know that?’

‘And you’ve got a good torch in the car.’

‘No,’ admitted Morse. ‘I’m afraid—’

‘Never mind, sir! We’ve got about half an hour before it gets too dark.’

It was twenty minutes to four when Lewis emitted a child-like squeak of excitement from the narrow hallway.

‘Something here, sir! And I think, I

think

—’

‘Careful!

Careful

!’ muttered Morse, coming nervously alongside, a triumphant look now blazing in his

blue-grey eyes.

Gradually the paper was pulled away as the last streaks of that December day filtered through the filthy skylight above the heads of Morse and Lewis, each of them looking occasionally at the

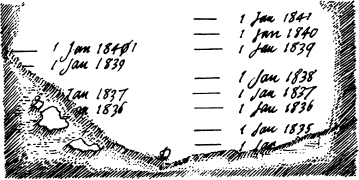

other with wholly disproportionate excitement. For there, inscribed on the original plaster of the wall, below three layers of subsequent papering – and still clearly visible – were two sets of

black-pencilled lines: the one to the right marking a series of eight calibrations, from about 3

'

6

"

of the lowest one to about 5

'

of the top, with a full date shown for each;

the one to the left with only two calibrations (though with four dates) – a diagonal of crumbled plaster quite definitely precluding further evidence below.

For several moments Morse stood there in the darkened hallway and gazed upon the wall as if upon some holy relic.

‘Get a torch, Lewis! And a tape-measure!’

‘Where—?’

‘Anywhere. Everybody’s got a torch, man.’

‘Except you, sir!’

‘Tell ’em you’re from the Gas Board and there’s a leak in Number 12.’

‘The house isn’t

on

gas.’

‘Get

on

with it, Lewis!’

When Lewis returned, Morse was still considering his wall-marks – beaming as happily at the eight lines on the right as a pools-punter surveying a winning-line of

score-draws on the Treble Chance; and, taking the torch, he played it joyously over the evidence. The new light (as it were) upon the situation quickly confirmed that any writing below the present

extent of their findings was irredeemably lost; it also showed a letter in between the two sets of measurements, slightly towards the right, and therefore probably belonging with the second

set.

The letter ‘D’!

Daniel!

The lines on the right

must

mark the heights of Daniel Carrick; and, if that were so, then those to the left were those of

Joanna Franks

!

‘Are you thinking what I’m thinking, Lewis?’

‘I reckon so, sir.’

‘Joanna married in 1841 or 1842’ – Morse was talking to himself as much as to Lewis – ‘and that fits well because the measurements end in 1841, finishing at the

same height as she was in 1840. And her younger brother, Daniel, was gradually catching her up – about the same height in 1836, and quite a few inches taller in 1841.’

Lewis found himself agreeing. ‘And you’d expect them that way round, sir, wouldn’t you? Joanna first; and then her brother, to Joanna’s right.’

‘Ye-es.’ Morse took the white tape-measure and let it roll out to the floor. ‘Only five foot, this.’

‘Don’t think we’re going to need a much longer one, sir.’

Lewis was right. As Morse held the ‘nought-inches’ end of the tape to the top of Joanna’s putative measurements, Lewis shone the torch on the other end as he knelt on the dirty

red tiles. No! A longer tape-measure was certainly not needed here, for the height measured only 4

'

9", and as Lewis knew, the woman who had been pulled out of Duke’s Cut had been

5

'

3

3

⁄

4

" – almost seven inches taller than Joanna had been after leaving Spring Street for her marriage! Was it possible – even wildly possible – that she had

grown those seven inches between the ages of twenty-one and thirty-eight? He put his thoughts into words:

‘I don’t think, sir, that a woman could have—’

‘No, Lewis – nor do I! If not impossible, at the very least unprecedented, surely.’

‘So you were right, sir …’

‘Beyond any reasonable doubt? Yes, I think so.’

‘Beyond

all

doubt?’ asked Lewis quietly.

‘There’ll always be that one per cent of doubt about most things, I suppose.’

‘You’d be happier, though, if—’

Morse nodded: ‘If we’d found just that

one

little thing extra, yes. Like a ‘J’ on the wall here or … I don’t know.’

‘There’s nothing else to find, then, sir?’

‘No, I’m sure there isn’t,’ said Morse, but only after hesitating for just a little while.

HAPTER

F

ORTY

The world is round and the place which may seem like the end may also be only the beginning

(

Ivy Baker Priest

, Parade)

I

T SOUNDED AN

anti-climactic question: ‘What do we do now, sir?’

Morse didn’t know, and his mind was far away: ‘It was done a long time ago, Lewis, and done ill,’ he said slowly.

Which was doubtless a true sentiment, but it hardly answered the question. And Lewis pressed his point – with the result that together they sought out the site-foreman, to whom, producing

his warranty-card, Morse dictated his wishes, making the whole thing sound as if the awesome authority of MI5 and MI6 alike lay behind his instructions regarding the property situated at Number 12

Spring Street, especially for a series of photographs to be taken as soon as possible of the pencil-marks on the wall in the entrance hall. And yes, the site-foreman thought he could see to it all

without too much trouble; in fact, he was a bit of a dab hand with a camera himself, as he not so modestly admitted. Then, after Lewis had returned torch and tape-measure to a slightly

puzzled-looking householder, the afternoon events were over.

It was five minutes to six when Lewis finally tried once again to drive away from the environs of Derby (North) and to make for the A52 junction with the M1 (South). At 6 p.m.,

Morse leaned forward and turned on the car-radio for the news. One way or another it had been a bad year, beset with disease, hunger, air crashes, railway accidents, an oil-rig explosion, and

sundry earthquakes. But no cosmic disaster had been reported since the earlier one o’clock bulletin, and Morse switched off – suddenly aware of the time.

‘Do you realize it’s gone opening time, Lewis?’

‘No such thing these days, sir.’

‘You know what I mean!’

‘Bit early—’

‘We’ve got something to celebrate, Lewis! Pull in at the next pub, and I’ll buy you a pint.’

‘You

will

?’

Morse was not renowned for his generosity in treating his subordinates – or his superiors – and Lewis smiled to himself as he surveyed the streets, looking for a pub-sign; it was an

activity with which he was not unfamiliar. ‘I’m driving, sir.’

‘Quite right, Lewis. We don’t want any trouble with the police.’

As he sat sipping his St Clements and listening to Morse conducting a lengthy conversation with the landlord about the wickedness of the lager-brewers, Lewis felt inexplicably

content. It had been a good day; and Morse, after draining his third pint with his wonted rapidity, was apparently ready to depart.

‘Gents?’ asked Morse.

The landlord pointed the way.

‘Is there a public telephone I could use?’

‘Just outside the Gents.’

Lewis thought he could hear Morse talking over the phone – something to do with a hospital; but he was never a man to eavesdrop on the private business of others, and he walked outside and

stood waiting by the car until Morse re-appeared.

‘Lewis – I, er – I’d like you just to call round quickly to the hospital, if you will. The Derby Royal. Not too far out of our way, they tell me.’

‘Bit of stomach trouble again, sir?’

‘No!’

‘I don’t think you should have had all that beer, though—’

‘Are you going to drive me there or not, Lewis?’

Morse, as Lewis knew, was becoming increasingly reluctant to walk even a hundred yards or so if he could ride the distance, and he now insisted that Lewis park the Lancia in

the AMBULANCES ONLY area just outside the Hospital’s main entrance.

‘How long will you be, sir?’

‘How long? Not sure, Lewis. It’s my lucky day, though, isn’t it? So I may be a little while.’

It was half an hour later that Morse emerged to find Lewis chatting happily to one of the ambulance-men about the road-holding qualities of the Lancia family.

‘All right, then, sir?’

‘Er – well. Er … Look, Lewis! I’ve decided to stay in Derby overnight.’

Lewis’s eyebrows rose.

‘Yes! I think – I think I’d like to be there when they take those photographs – you know, in, er …’

‘

I

can’t stay, sir! I’m on duty tomorrow morning.’

‘I know. I’m not asking you to, am I? I’ll get the train back – no problem – Derby, Birmingham, Banbury – easy!’

‘You

sure

, sir?’

‘

Quite

sure. You don’t

mind

do you, Lewis?’

Lewis shook his head. ‘Well, I suppose, I’d better—’

‘Yes, you get off. And don’t drive too fast!’

‘Can I take you – to a hotel or something?’

‘No need to bother, I’ll – I’ll find something.’