The Year of Shadows (42 page)

Read The Year of Shadows Online

Authors: Claire Legrand

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Fairy Tales & Folklore, #General, #Social Issues, #Friendship, #Action & Adventure

“Mine, too,” gushed Henry. “Mr. Thompson, sir—er, Maestro Thompson—I’m a huge fan. Do you think you could sign my algebra homework?”

“Won’t you have to turn that in?”

“No way, sir. I’ll take the zero.”

While Henry worshipped at the feet of Maestro Thompson, I took the chance to slip away. I wanted to hear the rehearsal, but there was something I needed to do first.

Ted—Mr. Banks—was sitting at the back of the Hall to watch rehearsal. He jumped to his feet when he saw me.

“You all right, Olivia?” He put his hands on his hips and grinned at the stage like the happiest guy alive. “Isn’t this great? This is going to be something else. Your dad’s gonna love this.”

He wasn’t Henry’s real dad, but he had the same huge smile. I was going to like him, I could tell. “Mr. Banks? I need a ride.”

O

NCE THE NURSES

gave me the okay, I walked into the Maestro’s room, right up to the side of his bed. I wouldn’t avoid him anymore. Not now, not ever again. If my ghosts could face Death, I could face this.

He stared at me, his mouth full of pudding.

“Sir,” I blurted. “Er. Maestro. I mean . . . hi.”

The Maestro swallowed and put down his spoon. “Hello, Olivia.”

“How are you feeling?”

“Much better, now that I have had some pudding.”

“Yeah.” I twisted the edge of his sheet between my hands. “The orchestra is rehearsing. I thought you should know.”

“Rehearsing? For what? With whom?”

“With friends.” That was the easiest way to say it. “And for . . . well, for you. I think it’s supposed to be a surprise, but I thought you’d want to know. To cheer you up.”

The Maestro folded his hands in his lap and stared at them. “What are they rehearsing?”

“Mahler 2.” I took a deep breath. “For a farewell concert. For you and for the Hall.”

The Maestro nodded slowly. “Yes. Perhaps it is time after all.”

“I guess.” I tried to swallow and it came out this shaky-sounding hiccup. “I’ll miss it.”

“Olivia, I’m sorry.”

Shadows don’t cry. Someday-famous artists don’t cry. I twisted the sheet as hard as I could. “Yeah?”

“For everything, Olivia. I know I haven’t been a good father. Not since your mother left, and maybe not for a long time before that too.”

Sometimes it isn’t okay when people say they’re sorry. At least not at first. “Yeah. I noticed.”

“You notice many things, don’t you?”

I looked up at the smile in his voice, but then I saw his arm. “When do you get those tubes taken out?”

“Soon, I hope. Why?”

“I don’t like them.” I kept twisting the sheet, but it didn’t help. I burst into tears. “I don’t like them at all.”

The Maestro took hold of my hand. He held it for a long time and didn’t say anything until I had finished. I was glad. I needed to finish.

“This might be my last concert ever, Olivia. You know that, don’t you? Not just with this orchestra, not just at the Hall.” He leaned back in his bed and winced. “It’s been a hard year. I’m not sure I’ll be the same now, if that makes sense.”

I wiped my nose with my arm. “Yeah. It does. I’ve changed too.”

“Have you?” The Maestro considered me for a long moment. “How are the ghosts, Olivia?”

Was he making fun of me? Was he angry? Or did he really want to know? Had he believed me this whole time? I couldn’t tell, and I didn’t care. “They’ve gone home.”

The Maestro nodded, settled back more comfortably. “I see.”

“I saw Mom.”

“You—” He turned to me, his face going all strange. “Where?”

“You saw her too, didn’t you? That’s why you walked around all the time at night. You thought you saw her, and you kept looking for her.”

“Perhaps,” he said slowly.

“I helped her to move on. At least I think so.”

I was her anchor

, I thought, because I’d been thinking it a lot. Sometimes it made me cry to think it, but more often it just made me feel light inside. “She said she was sorry, and that you showed her beautiful things. She said you’re a good man.”

“Did she?” The Maestro smiled then, the biggest I’d seen him in a while. We had the same smile, I noticed. I’d forgotten. “Well. I’m glad.”

I’m not sure he believed me. But I think he liked what I said anyway. I think it was nice to imagine.

Sometimes that’s how you get through things.

MAY

T

HE NIGHT OF

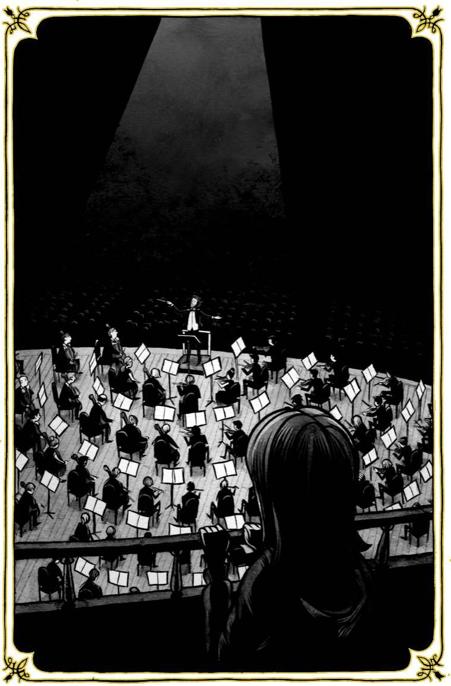

the Mahler 2 concert, on the first weekend of May, I settled down on the catwalk with Igor to keep me company. Technically, I wasn’t supposed to be up there, especially now. But it was the last time, and I knew this catwalk like I knew my sketchpad, inside and out.

Far below us, the Hall crawled with people—in jeans, in furs, kids and college students and grown-up people, and reporters. A lot of them, with cameras and notepads and flashing lights, the whole deal. Mayor Pitter and a group of important-looking people, surrounding him in suits and ties. Mr. Rue, smiling like a kid. The Barskys in greens and yellows, and their ghost entourage, of course. Joan, with her parents. She waved up at me like I was a rock star.

Igor jumped down from the railing.

Where’s your sketchpad, by the way? I would think this would be terribly inspiring.

“It is, but not tonight. Tonight is different. Tonight is just for this.”

Henry hurried up the stairs and settled next to me with

his jar. When I raised my eyebrows, he shrugged. “I want them to see this.”

He didn’t need to explain who “them” was, not to me. How completely wonderful and strange.

“What are you smiling about?” Henry said.

“Everything.”

“You’re freaking me out. Where’s the scary Olivia, with the attitude and the crazy pictures?”

“She’s still there. This morning, I drew a man made out of bloody tubes. And a giant with three heads. And I might have accidentally slipped something stinky into Mark Everett’s backpack.”

“See, that’s more like it.”

“Henry?”

“Yeah.”

I threaded my fingers through the grated floor. “I’m going to talk to Counselor Davis about art school. You know, for later. I want to get started looking into it now. Do you think that’s crazy?”

“No.” Henry lay back and propped his feet up on the railing. “I think it’s great, Olivia.”

“That’s not very proper behavior for an usher.”

“If I don’t lie down, I’ll fall over. I’m so nervous.”

“You shouldn’t be.” I looked over the edge and found Richard Ashley’s sandy brown head. He gave me a thumbs-up. I waved back. “They’ll be fine. They’ll be better than fine.”

And they were. From the moment the lights went down

(Ed kept pulling at his collar and Larry kept muttering how he’d never been more nervous in his whole life) and the Maestro stepped out onto the stage with his cane (he had to walk with one now), everything was better than fine.

Because nobody cared that a month ago, there’d been ghosts here, scaring people, and shades crashing down ceilings. They didn’t care about our petition or the fact that I lived backstage or the rumors that had been flying around.

Not once the orchestra started playing.

They just watched, and listened. In the pauses between movements, you could have heard a shade slithering around, it was so silent. But shades didn’t come around here anymore. I wondered if it was because of Mom.

“This is incredible,” Henry whispered, about halfway through the finale. It was the first time either of us had spoken. You couldn’t speak, not with the strings soaring like they were, all the musicians’ arms sweeping at the same time. Not with the cymbals crashing, and the timpanist thundering on his drums, mallets flying. Not with the trumpets blaring their fanfare way up high, and the rest of the orchestra rumbling underneath them.

I peeked over the railing as the orchestra quieted down to a lullaby—the horns crooning, the violinists’ bows kissing their strings, the chimes ringing like a clock. When I looked down at the audience, I saw that open, soft look on their faces. People watched with hands over their mouths, people clutched their neighbors’ arms. A

boy on his father’s lap stared at the choir, eyes shining.

That’s when I realized all that was happening behind the Maestro’s back. He wasn’t seeing it. He

couldn’t

see it.

I watched his arms stroking the air, guiding the piccolo player up and up. His shoulders bunched up near his ears.

Quiet.

That’s what he was saying to the orchestra:

Quiet, here. Quiet, now. Hush.

The musicians watched him, just as attentive as the audience. They could see his face.

But I couldn’t.

And suddenly, I needed to.

“I’ve gotta go,” I whispered to Henry.

“What?” Henry grabbed my arm. “Are you kidding me? They’re at

Etwas bewegter

!”

I stared at him. “Henry, please don’t tell me you speak German, too.”

“No, but I did memorize the lyrics. And the major tempo markings.”

I rolled my eyes. “Oh, well, if that’s all. But seriously, I have to go.”

“Where are you going?”

“To the organ loft.” It seemed like the best place. “I want him to see me.”

After a second, Henry nodded and let go of me. “You should.”

“Come with me?”

“I don’t think your dad cares about seeing me.”

“Maybe not. But I do.”

Henry beamed and took my hand. “Yeah?”

“Yeah. Come on. Igor?”

Igor thumped his tail at me.

Oh, so you

were

going to ask. That’s nice to know.

“Igor . . .”

He stretched out in that lazy way only cats can do.

I’m far too comfortable here. Besides, organ lofts are dusty.

As the alto solo continued, Henry and I crept across the catwalk, past Larry and Ed, who watched the concert with the goofiest smiles on their faces. I don’t think they even noticed us walk by. We hurried down the utility stairs and backstage, past my empty bedroom.

Toward the end, when the choir stood up in one quick motion, we heard it boom over our heads.

“We should hurry,” Henry said.

Nonnie sat backstage, bundled up in her scarves and watching the concert on the monitor.

“Oh, Olivia!” she cried, waving at us. “I’m watching, with my favorite scarf!

Molto stupendo, assolutamente perfetto!

”

I stopped long enough to kiss her cheek. “That’s great, Nonnie.”

We climbed up the zigzagging loft stairs as they vibrated with the force of the organ over our heads. The pipes surrounding us shook my teeth, making it hard to stay balanced, but finally we made it to the organist’s door. Past that loomed the entire, glittering, packed Hall.

And the Maestro.

Together, we opened the organ loft door. I stepped out first, into the blinding light.

With my hand on the doorknob, I hesitated.

“What’s wrong?” Henry had to bellow to be heard.

Lots of things, really. Mom was dead. The Maestro had to walk with a cane. I didn’t know where we would be after the next few days, what would happen to the people playing onstage, to the Hall, to us. Would donations increase? Could we save the Hall after all? Or was it too late?