There is No Alternative (17 page)

Read There is No Alternative Online

Authors: Claire Berlinski

“One of those female types,” I say, “and we all know them, who likes to be the center of male attentionâ”

“Absolutely!” says John.

“

That's

it,” says Miranda simultaneously.

That's

it,” says Miranda simultaneously.

“

Absolutely

,” agrees John again, nodding vigorously.

Absolutely

,” agrees John again, nodding vigorously.

“And there was one occasion,” Miranda recalls, “when she literally, when I was saying good-bye, literallyâshe used to do this to a lot of peopleâshe'd take your hand to say good-bye, and you were just hoping to have a word or two, to say thank youâand she'd just

sweep

you out, and wait for the man to comeâit's very, very weird.”

sweep

you out, and wait for the man to comeâit's very, very weird.”

“Like some old-fashioned Hollywood diva,” I say.

“Yes! Yes!” agrees John.

So what was it like, I ask, when this diva entered the room?

“She'd always be very correctly dressed,” Miranda says, “with all the jewelry in the right place.”

“

Quick

,” adds John. “A quick, funny, shuffling walk. Comes in through the door at very high speed and immediately shows off like mad to show she's arrivedâ”

Quick

,” adds John. “A quick, funny, shuffling walk. Comes in through the door at very high speed and immediately shows off like mad to show she's arrivedâ”

“Yes,

shows off

! She was a great shower-off. I mean, at the end of parties, when you were invited to stay and have a drink with her before she went off to the House of Commons, she would throw off her shoes, and sit down on the sofa with her feet up, and everyone would sort of cluster 'round herâwhich I used to feel very uncomfortable aboutâyou know, everyone looking at her with worship. And she just showed off. Non-stop. Again, back to the

diva, you know. Very much that sort of thing. But I'm thinking back to when I actually met her. JohnâI was hoping I would have met her the night of the election, when we were around atâumâCentral Office?”

shows off

! She was a great shower-off. I mean, at the end of parties, when you were invited to stay and have a drink with her before she went off to the House of Commons, she would throw off her shoes, and sit down on the sofa with her feet up, and everyone would sort of cluster 'round herâwhich I used to feel very uncomfortable aboutâyou know, everyone looking at her with worship. And she just showed off. Non-stop. Again, back to the

diva, you know. Very much that sort of thing. But I'm thinking back to when I actually met her. JohnâI was hoping I would have met her the night of the election, when we were around atâumâCentral Office?”

“Central Office,” he agrees.

“Once it became clear that she was in, and she was going to be elected, John came 'round and said, âOK, let's go home and watch it on television.' And I said, âBut I've never

met

her!' He said, âI don't care, I've

got

to get out of this.' And as we left, all the newspapermen outside the door, saying, â

She's coming! She's on her way

!' And I couldn't get back in again! I had to go home and watch it on television! I missed the whole thing. So I didn't meet her until well after that. And she took hold of my hand, in a very friendly way, and said”âhere Miranda breaks into a perfect impression of Thatcher's imperious, regal voiceâ“âOh, well, I

do

hope you can spare your husband. You've got

lots

of things you like to do yourself, haven't you.' She didn't

ask

me whether I had, she

told

me!”

met

her!' He said, âI don't care, I've

got

to get out of this.' And as we left, all the newspapermen outside the door, saying, â

She's coming! She's on her way

!' And I couldn't get back in again! I had to go home and watch it on television! I missed the whole thing. So I didn't meet her until well after that. And she took hold of my hand, in a very friendly way, and said”âhere Miranda breaks into a perfect impression of Thatcher's imperious, regal voiceâ“âOh, well, I

do

hope you can spare your husband. You've got

lots

of things you like to do yourself, haven't you.' She didn't

ask

me whether I had, she

told

me!”

Miranda is too charitable to dwell for long on these memories. “She was devoted to Denis,” she adds. “She

adored

himâ”

adored

himâ”

“Yes, yesâ” John nods vigorously.

“She was delightful. Now, you would expect someone like that to have a henpecked husband, who she was always telling what to do. Not a bit of it! She was very, very considerate and sweet to him. Really delightful.”

“Did she have a sense of humor?” I ask.

“She did,” says John, “but it only showed up every now and then . . . the only time I remember making her laugh was when we were sitting in the long library at Chequers, trying to write a speech. And there'd been a great scandal about a Labour shadow minister who'd been caught up in some enormous affair with a married woman, which had upset his political career, and there was a picture of him at an air display at Farnborough sitting next to the queen.” John begins laughingâin fact, he begins laughing so hard that the next part of his story is unintelligible. “And of course there was the implication of all journalism, that, you

know, he'd been shagging this bird, and was absolutely . . .” Now they are

both

doubled over with laughter. I have no idea what's so funny. “And I was there with the paper, saying, you know, âThis man must go!' And she absolutely fell about! And I remember her being fairly obvious and saying he needed a quick forty winks, you know! And to my astonishmentâshe really thought that was funny!”

know, he'd been shagging this bird, and was absolutely . . .” Now they are

both

doubled over with laughter. I have no idea what's so funny. “And I was there with the paper, saying, you know, âThis man must go!' And she absolutely fell about! And I remember her being fairly obvious and saying he needed a quick forty winks, you know! And to my astonishmentâshe really thought that was funny!”

Â

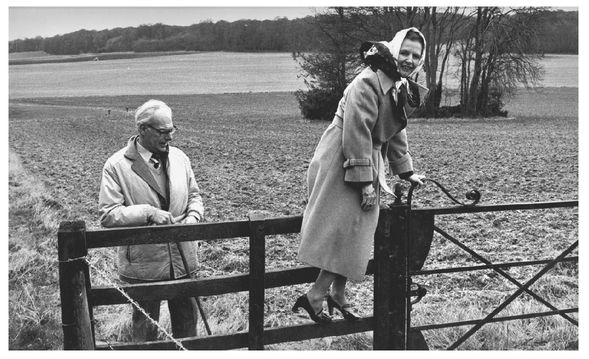

This photograph of Denis and Margaret Thatcher immediately puts me in mind of columnist Julie Burchill's wonderful description of their marriage: “Denis was so supremely self-confident/drunk that he didn't give a fig about being seen as an alpha woman's consort; with the quiet, amused, ceaseless tolerance of the little woman's little ways typical of the real man, he was a tower of strength disguised as a bumbling buffoonânever the cretinous yes-man caricature portrayed by some weird lefties who, while paying lip service to feminism, seemed decidedly uncomfortable at the sight of a man walking behind a woman.”

(Courtesy of the family of Srdja Djukanovic)

(Courtesy of the family of Srdja Djukanovic)

I later listened to this part of the transcript several times, trying to figure out what he was talking about. I'm still not sure. Perhaps you had to be there.

“Yes,” says Miranda, “she quite likedâ”

“Slightly raunchy humor,” he finishes for her.

“Yes, she quite liked raunchy humor with the

boys

, but again, would never have done with women!”

boys

, but again, would never have done with women!”

“No!” he agrees.

“You know, she loved to be thought of as one of the boys, making slightly risqué jokesâ”

They are enjoying these memories. As they finish each other's sentences, their eyes meet and sparkle with affection. One can never know what another couple's marriage is really like, but they certainly give the impression that theirs is the very ideal of what marriage ought to be. This, I think, must be why Miranda is so sanguine about the prime minister's rudeness to her: Only a very well-loved woman could be so charitable.

Margaret Thatcher may have liked to think of herself as one of the boys. The boys, I gather, did not quite think of her as one of them. But one of the

men

âthat's another story. “Reagan, Gorbachev, and Thatcher,” says John, “that triumvirateâjust amazing. She could just walk the world stage by then, looking like a million dollars, with a fur hat on, in Warsaw, through the snow, and we thoughtâthis woman was a

star

! And not only that, but unlike the French people, her economy isn't in trouble. You know, her economy, now everyone is looking to it, saying, âPerhaps this is the way we should do things!' And now here she is, saying, âThis is the way the West has got to deal with the Soviets!'”

men

âthat's another story. “Reagan, Gorbachev, and Thatcher,” says John, “that triumvirateâjust amazing. She could just walk the world stage by then, looking like a million dollars, with a fur hat on, in Warsaw, through the snow, and we thoughtâthis woman was a

star

! And not only that, but unlike the French people, her economy isn't in trouble. You know, her economy, now everyone is looking to it, saying, âPerhaps this is the way we should do things!' And now here she is, saying, âThis is the way the West has got to deal with the Soviets!'”

The footage of Thatcher in Poland is indeed unforgettable.

79

In 1988, as the Polish economy was collapsing and the Solidarity movement was gaining strength, Prime Minister Wojciech Jaruzelski invited Thatcher to visit Poland. He was presumably hoping to enlist the support of the woman who had vanquished her unions in Britain; perhaps he expected a cozy tête-à -tête, one union-crusher to another.

80

He was to be severely disappointed. As a condition

of her visit, Mrs. Thatcher demanded the communist government allow her to meet Solidarity leader Lech Walesa. They agreed. “You didn't say no to Mrs. Thatcher,” Lech Walesa recalled. “No one refused her.”

81

79

In 1988, as the Polish economy was collapsing and the Solidarity movement was gaining strength, Prime Minister Wojciech Jaruzelski invited Thatcher to visit Poland. He was presumably hoping to enlist the support of the woman who had vanquished her unions in Britain; perhaps he expected a cozy tête-à -tête, one union-crusher to another.

80

He was to be severely disappointed. As a condition

of her visit, Mrs. Thatcher demanded the communist government allow her to meet Solidarity leader Lech Walesa. They agreed. “You didn't say no to Mrs. Thatcher,” Lech Walesa recalled. “No one refused her.”

81

She sailed into the Lenin shipyard at Gdansk aboard a small ship. The docks were lined with vast throngs of shipyard workers dressed in their drab, oil-stained, Soviet-regulation boiler suits. Defying the police blockade, they climbed the gates and clambered atop the cranes and roofs surrounding the shipyards to catch a glimpse of her. In the video footage she seems literally to be casting light upon the grayness: It is almost as if she has been shot in Technicolor against a black-and-white background. Before the great crowds she passes, slowly, regally. The men and women in the crowd wave and wave and peer at her with hopeful reverence; they chant “

SolidarnoÅÄ! SolidarnoÅÄ!

” and

“Vivat Thatcher!”

SolidarnoÅÄ! SolidarnoÅÄ!

” and

“Vivat Thatcher!”

She lays a wreath at the monument to shipyard workers killed in 1970 by the security forces. The crowds roar as she addresses them:

“Solidarity was, is, and will be!” “Thatcher! Thatcher!” “Send the Reds to Siberia!”

Solidarity workers escort her to a packed church. There the entire congregationâfaces cragged and carewornâbegins, in unison, to sing the Solidarity anthem. The camera focuses on Thatcher's face. Her eyes are filled with tears.

“Solidarity was, is, and will be!” “Thatcher! Thatcher!” “Send the Reds to Siberia!”

Solidarity workers escort her to a packed church. There the entire congregationâfaces cragged and carewornâbegins, in unison, to sing the Solidarity anthem. The camera focuses on Thatcher's face. Her eyes are filled with tears.

It was at this point, I imagine, that Jaruzelski realized, his head sinking into his hands with horror, that he was completely and utterly finished.

Thinking of that scene, I remark to John and Miranda, “It's a very strange thing, political charisma. It's fascinating to try to understand what it is, and how it worksâ”

“

Fascinating

,” Miranda agrees. “And you do feel this ability of certain people to transmit itâit is a kind of magical thing.”

Fascinating

,” Miranda agrees. “And you do feel this ability of certain people to transmit itâit is a kind of magical thing.”

She had that magic, no doubt. But in the end, they both agree, there was something more than charisma at work. She had guts. John remembers the way she rose to the occasion on October 12, 1984, when an IRA bomb blasted apart the Brighton Grand Hotel. Thatcher and the members of her cabinet were staying there before the opening of the Conservative Party conference. The prime minister and her husband narrowly escaped injury, but five of her friends were killed. Margaret Tebbit, the wife of her cabinet minister Norman Tebbit, was paralyzed.

The bomb went off at 2:54 a.m. The prime minister wasâas usualâawake and working on her speech for the next day. “The air was full of thick cement dust,” she recalls in her memoirs. “It was in my mouth and covered my clothes as I clambered over discarded belongings and broken furniture towards the back entrance of the hotel.”

82

She was taken to the police station, where she changed from her nightclothes into a navy suit. Her friends and colleagues arrived, suggesting she return to Number 10. “No,” she said. “I am staying.”

83

Thenâand this is the detail that makes you realize that this woman is

not

like you and

not

like meâshe lay down and took a short nap, so to be fresh for the long day ahead of her. After she woke she took breakfast, she recalls, with plenty of black coffee.

82

She was taken to the police station, where she changed from her nightclothes into a navy suit. Her friends and colleagues arrived, suggesting she return to Number 10. “No,” she said. “I am staying.”

83

Thenâand this is the detail that makes you realize that this woman is

not

like you and

not

like meâshe lay down and took a short nap, so to be fresh for the long day ahead of her. After she woke she took breakfast, she recalls, with plenty of black coffee.

Hours after surviving an assassination attempt, she walked into the conference center at 9:30 a.m., precisely on time. She delivered her speech, partly ad-libbed. “The bomb attack,” she began,

. . . was an attempt not only to disrupt and terminate our conference. It was an attempt to cripple Her Majesty's democratically elected Government. That is the scale of the outrage in which we have all shared. And the fact that we are

gathered here nowâshocked, but composed and determinedâis a sign not only that this attack has failed, but that all attempts to destroy democracy by terrorism will fail.

84

gathered here nowâshocked, but composed and determinedâis a sign not only that this attack has failed, but that all attempts to destroy democracy by terrorism will fail.

84

Other books

My Guardian (Bewitched and Bewildered Book 6) by Alanea Alder

Safe From the Dark by Lily Rede

Just Plain Pickled to Death by Tamar Myers

Cookie Cutter by Jo Richardson

The Pleasure of My Company by Steve Martin

Called by the Bear 1-3 by V. Vaughn

The Rubber Band by Rex Stout

Our Brothers at the Bottom of the Bottom of the Sea by Jonathan David Kranz

Oaxaca Journal by Oliver Sacks, M.D.

I Heart London by Lindsey Kelk