They Marched Into Sunlight (5 page)

Read They Marched Into Sunlight Online

Authors: David Maraniss

Tags: #General, #Vietnam War; 1961-1975, #History, #20th Century, #United States, #Vietnam War, #Military, #Vietnamese Conflict; 1961-1975, #Protest Movements, #Vietnamese Conflict; 1961-1975 - Protest Movements - United States, #United States - Politics and Government - 1963-1969, #Southeast Asia, #Vietnamese Conflict; 1961-1975 - United States, #Asia

Sons of bitches.

Jim George was stunned. His “blood boiled” as he thought to himself, “Aren’t those the guys pulling the triggers and doing the fighting and dying?”

Chapter 2

Triet’s March South

V

O

M

INH

T

RIET

had been fighting in the war fields between Saigon and the Cambodian border for more than six years by the summer of 1967. To the American soldiers at Lai Khe, he was the enemy, out there somewhere beyond the concertina wire, and all they had to do was go out and find him.

Each of us has our own situation, Triet once explained, and his went like this: He was a southerner, the sixth child born into a farm family in the district of Ba Tri near the mouth of one of the Nine Dragons, or branches, of the Mekong River. Near the end of the summer of 1945, when he was fifteen, his life was reshaped by circumstances beyond his adolescent horizon. The wartime Japanese occupiers had left, a declaration of independence had been issued in Hanoi, and the long struggle to rid Vietnam of the French colonialists had begun anew. Ba Tri was a stronghold of the liberation movement. Less than a mile from Triet’s rural home stood the revered tomb of Nguyen Dinh Chieu, the great blind poet of the South whose patriotic verse a century earlier had inspired his countrymen as they took up arms against foreign occupation. “Better to die fighting the enemy and to return to our ancestors in glory / Than to survive in submission to the Western strangers.”

Triet quit school and joined the resistance against the French, just as his father had done. First he was in a youth brigade, later in the army of the Viet Nam Doc Lap Dong Minh Hoi, the Allied Vietnamese Independence League known as the Viet Minh. He was wounded in the right shin in 1952 during a battle in Kien Giang Province, but kept fighting until the French were defeated in 1954. At that point much of Vietnam was controlled by the Viet Minh, but its fate was determined by outsiders. The larger Communist powers, led by the Soviet Union and China, pushed the Viet Minh to accept the Geneva accords dividing Vietnam in two. It was to be a temporary separation until elections could be held to reunify the nation in the summer of 1956. Triet and his unit marched north to await the national elections, which never happened. The government in the South, with the Eisenhower administration its primary benefactor, declared that the North’s aggression in the aftermath of Geneva negated the agreement.

In the first days of 1961 Triet took the first steps toward the final battlefield of our story, walking back toward his native South with one of the first units of North Vietnamese forces to take up the fight against the U.S.-supported Saigon regime. He was thirty by then, an old warrior by military standards but one of the younger men of a squad whose average age was thirty-five. His comrades, like him, were transplanted southerners who had fought the French. For twenty nights before leaving, they had trained for the winding journey down Vietnam’s treacherous spine by walking three hours through the countryside beyond the Xuan Mai barracks south of Hanoi. Triet, weighing 121 pounds, trained by hauling a pack loaded at nearly half his weight. It was drudgery, he thought, but there was gratification at the end of each outing when they returned to camp and were given limeade and porridge and maybe some beer or

quoc lui,

rice whisky that to them tasted finer than Russian vodka.

In the official military history of Triet’s regiment, published decades later, there is mention of a final meeting in Hanoi with the two leading figures of the Vietnamese revolution, Communist Party chairman Ho Chi Minh, referred to affectionately as Uncle Ho, and Senior General Vo Nguyen Giap, hero of the defeat of the French at Dien Bien Phu. It was reported that Giap, after briefing these southbound troops on their duties, “chatted with them cordially and open-heartedly” and asked, “Comrades, once in the South, where will you find guns to fight the enemy?” To which came the reply, “General, we will carry guns from the North to kill the enemy and take their weapons.” Later that evening Uncle Ho gave the soldiers four pieces of advice. First, maintain unity. Second, preserve secrecy. Third, act in coordination with new comrades. And fourth, be prepared “to go anywhere and do any work assigned by the party…and refrain from making demands.” The troops were said to be “extremely moved” by Ho’s “sagacious instructions” and promised to heed his teachings. So went the myth.

The poetic and the harsh converge in Vietnam. From that glorified rendition of a noble sending-forth followed two months and twenty-seven brutal days. Triet and his comrades were transported by truck down Route 1 to Ha Tinh, then west toward the mountains near the border with Laos, and from there they walked more than six hundred miles south through the wilderness along the Truong Son range. They carried French-made MAS (modern army supply) rifles, a few Thompson submachine guns, radio equipment, and medical supplies. There was no road, only the most primitive semblance of what Americans later would call the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The route over and around densely forested mountains was marked by broken twigs left by advance scouts. Three weeks of training gave Triet little warning of how exhausted he would feel after only the first day. His boots made his feet swell, so he took them off and tied them around his shoulders, then threw them away altogether and replaced them with rubber-tire sandals.

The sandals were less slippery on mountain slopes and also more effective when it came to tree leeches. If a soldier wore boots, the tree leeches could dig in, but with sandals at least they could be spotted immediately. The sight and sound of tree leeches haunted every man who marched down the Truong Son trail. Triet saw no tigers along the way, nor did he encounter enemies from the Saigon Special Forces, but he would never forget the tree leeches. They lived under leaves that fell from the trees, and when troops came by, the creatures smelled a human feast approaching. Triet and his comrades would hear a cranky

yrrow, yrrow

sound and see the trail move and the leaves rustle, and they knew that beneath the leaves tens of thousands of leeches were heading toward them en masse. The audacious bloodsuckers were about the size of pen tips before they gorged. They attached themselves in spherical hordes.

Salt was among the most precious rations Triet carried. It was meant for cooking, but he used it for another purpose. At the end of the day he wrapped a piece of cloth around the tip of a stick and soaked it in salted water. This became his leech-removing prod for the next morning; the salt would make leeches jump from his feet. Instead of salt for flavoring, Triet and his squad often used the ash from charcoal to flavor their meals, which usually consisted of pressed rice along with greens they had picked along the way. Every hour they took a ten-minute break to gather food for dinner, collecting what they could find at the side of the trail: mostly bamboo sprouts and greens known as machete heads and airplane heads. When they reached camp for the night, they gathered and washed the greens, boiled them, spread them out on two nylon ponchos, and took out their chopsticks for a communal dinner.

Lunch was a small portion of pressed rice, if available, and for energy in the early afternoon Triet reached into his pocket and pulled out a tiny piece of the hundred grams of ginseng that he had bought in a traditional medicine shop in Hanoi. At an aid station in the Central Highlands, where there was no rice, his squad was provided a can of corn. It was divided evenly among the men, twenty kernels per soldier a day. During one stretch near the end of the march, they went seven days without rice. The storage bins at an aid station were empty, and the commander decided that if they waited around for rice, they might all get sick and die and have no one to bury them, so they kept moving. For morning sustenance they relied on what they jokingly called

ca-phe doc,

which means “hill coffee”—not the sort one would buy at the market. Every night, if possible, Triet and his squad camped next to a stream, which meant they were in a low-lying drainage area and the walk the next morning would be on a steep incline up the next mountain. They usually walked uphill from dawn until ten or eleven before reaching a crest, and this difficult ascent was their hill coffee because it unfailingly woke them up.

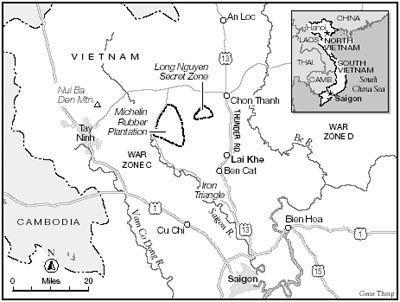

The first southbound troops reached their destination on March 27. Triet’s squad arrived weeks later. Their new headquarters were at two base camps, one hidden deep in the jungle of War Zone C near the Cambodian border above Tay Ninh, about sixty miles to the northwest of Saigon, and another across the Saigon and Song Be rivers to the northeast in War Zone D. The camps were on the rim of a larger region of Vietnam called Eastern Nam Bo, where many native southerners had fought the French in the early 1950s. Abandoned tunnels and trenches from that earlier struggle were still evident. “Eastern Nam Bo is full of hardships but exudes gallantry,” troops had sung as they left the region to relocate in the North in 1954. Now they were back in this familiar landscape where they would fight and die for another fourteen years.

Once in the South, the soldiers were reorganized into fighting units, part of the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN). Vo Minh Triet, whose war name was Bay Triet, became part of a regiment with the code name Q761, a designation taken from its official founding in July 1961. A few months later, on the second of September, the national day in the North, Triet and his comrades were officially designated the First Regiment at a ceremony in the shadows of Nui Ba Den, the Black Virgin Mountain, where they recited ten solemn oaths of faithfulness and solidarity and promised to fight to the end for the liberation of South Vietnam and national reunification. Over the next few years Triet’s regiment would take on other aliases, most notably the Binh Gia Regiment, an honorific bestowed upon it after a decisive battle in late 1964 against the South’s ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam) units near Saigon. American intelligence reports later identified it consistently as the 271st Regiment, though this was a name the unit itself never used. Q761, yes; First Regiment, yes; Binh Gia, yes; 271st, no. There never

was

a 271st, Triet later insisted.

After the victory at Binh Gia, nearly four years into the fight against what they called the puppet troops of Saigon, Triet and his comrades believed their opponents were near defeat. It was an assessment shared by the Johnson administration in Washington, and soon thereafter, starting with the landing of elements of the U.S. Ninth Marine Expeditionary Force at Da Nang in early March 1965, the forces of the communist-led People’s Army of Vietnam found themselves in a new sort of strategic war, dealing with ever-increasing numbers of American infantrymen on the ground and B-52s overhead.

The first full division of soldiers from the U.S. Army sent into Eastern Nam Bo in the summer and fall of 1965 belonged to the First Infantry, the old and proud Big Red One. By September 2, when Triet’s First Regiment was incorporated into the newly founded Ninth VC Division, his commanders knew much about these arriving Americans: the order of battle, the names and histories of generals and colonels, all the way down to the height and weight of the average soldier (1.8 meters and eighty kilos, compared to 1.6 meters and fifty kilos on their side).

The Big Red One

was translated into Vietnamese as “Big Red Brothers.” It was described in PAVN documents as an awesome force that had “a long history of warfare and had performed in an outstanding manner…in our military terminology, a unit that won a hundred battles in a hundred fights.” An exaggeration, perhaps, but close enough for propaganda.

There was concern that the Americans, with their vast supply of armored vehicles, helicopters, big guns, and bombs, were invincible. One VC Ninth Division colonel even claimed that with inferior firepower and equipment, he gave his men the option of not fighting the Americans if they felt overwhelmed. (He reported later that fifteen of two hundred soldiers took this offer.) “Would the division be able to handle the Americans? How should it fight to beat them? These were extremely pressing questions,” Ninth Division historians reported later. When Triet heard that the Americans were coming, his first thought was that the war would be “terrible and fierce.” As to whether it would be a long war or a short war, he was less certain. From Hanoi radio he had heard reports of the incipient antiwar movement in the United States and pronouncements from Uncle Ho that the disquiet within America might be as important as armed conflict in Vietnam. Shaping public opinion was a strategic aspect of the political struggle, which was always waged in concert with the war itself.

As for the Big Red Brothers, Triet thought they were strong in fire-power but also had potential weaknesses. What did they know about the people they were fighting and the land on which they fought?

Chapter 3

Lai Khe, South Vietnam

L

AI

K

HE,

pronounced

lie kay.

It was at once a small Vietnamese village, a French rubber plantation, and an American military base camp, three cultures interwoven by history and circumstance if not trust. Fences encircled the local village, which was swallowed whole by the larger oval of the military base. Who the fences were supposed to protect, or keep in or out, was never obvious. Villagers worked for the Big Red Brothers, washing laundry, cleaning rooms, burning shit, cutting hair, serving drinks, providing sex, but many were quietly supporting the other side, the Viet Cong. The French managers of the Michelin plantation rarely showed up, though they seemed to have scouts who knew everything; if rubber trees were cut down to give mortars a cleaner arc into the nearby jungle, an invoice was sure to arrive soon thereafter billing the First Division a few hundred dollars per felled tree. While damning the French, the Americans took full advantage of the splendid remains of the colonial plantation; the officer corps occupied a resortlike villa of white stucco and red tile houses complete with recreation center and swimming pool. That some of the larger buildings came with oversized basins once used for rubber experiments was but a minor inconvenience.