They Marched Into Sunlight (9 page)

Read They Marched Into Sunlight Online

Authors: David Maraniss

Tags: #General, #Vietnam War; 1961-1975, #History, #20th Century, #United States, #Vietnam War, #Military, #Vietnamese Conflict; 1961-1975, #Protest Movements, #Vietnamese Conflict; 1961-1975 - Protest Movements - United States, #United States - Politics and Government - 1963-1969, #Southeast Asia, #Vietnamese Conflict; 1961-1975 - United States, #Asia

Each soldier with his own story, yet if there was a prototype of the young men from Wisconsin who fought in Vietnam, it might be Daniel Patrick Sikorski. He was a third-generation Polish immigrant, the son of Edmund Sikorski, himself one of twelve children born to Joseph and Stella Sikorski, who came to Milwaukee from Krakow. Edmund Sikorski quit school after sixth grade and went to work, spending most of his career as a filler on the assembly line at Miller Brewing Company. He married Stella Kubiak, another southsider, and together they raised Danny and Diane in the familiar patterns of the Polish working class. They had a dog named Penny, vegetables in the backyard, a color portrait of Jesus in the living room, and latch hooks on the side door. There was a little cottage on Lake Lucerne up in Crandon where they enjoyed a two-week vacation every July and where Danny and Diane swam and fished, climbed the watchtower, and fed the deer. At Christmas they hung stockings on the fake fireplace, attended midnight mass and shared the

oplatek,

the blessed Polish wafers. Danny and Diane broke bread and exchanged good wishes and held their breath as they kissed cheeks and toasted with Mogen David wine. They went to church at Saint John Kanty and attended parish school in the early years. No one called him Ski on the south side. There would be no way to tell him apart from anyone else. His classmates in eighth grade were Tarczewski, Kucharski, Mikolajewski, Arciszewski, Mrochinski, Badzinski, Odachowski, Banaszynski, Kumelski, Benowski, Kitowski, Witowski, Szapowski, Kawczynski, Szutowski, Jaskolski, Moczynscki, Zlotkowski, Czerwinski, Kulwicki, and Danielewski.

In preparation for life as a tradesman, Danny attended Milwaukee Boys Tech, where he played football and took an apprenticeship at Harnischfeger, a tool manufacturing plant. He was extremely close to his mother, a light-hearted talker like him. They shared a love for professional wrestling, and when matches came to the Milwaukee Arena, where he worked part-time as an usher, he made sure that she got tickets. He fell into a depression when his mother died suddenly at age forty-three, before he had finished high school. Neither he nor Diane knew anyone in their neighborhood who had gone to college. When he got his draft notice, Danny and a buddy enlisted in the army. His last trip home before heading for Vietnam was a furlough in late February. By then his father had remarried and moved to the north side and there was no bedroom for him, so he slept in the cold basement. He rode the city bus back to his old neighborhood and visited the Saint John Kanty priest, Father Czaja, and confessed that he thought he was going to die.

That weekend he surprised Diane by popping in at her favorite hangout, Wyler’s teen bar. He sat at another table and watched her talk with friends until the end of the night, when he approached her table and asked her to dance. A slow song. “Are you sure you want to dance with me?” she asked. “Well, you’re my little sister, aren’t you?” It was their first dance together. Diane felt awkward at first, but Danny reassured her. He gave her advice about how to deal with boyfriends and what to do about their father and their new stepmother, and together they remembered the smell of their mom’s homemade soups. Back when Danny was born, his father had planted a pine tree by the side of the house on Eighth Street. Now, when the young soldier took a trip back to the old neighborhood, he noticed that the new owner had cut the pine tree down.

Diane started getting migraine headaches after Danny left, and she worried about their father, who would sit in his chair for hours and stare into space. She prized the letters her brother sent home, but no matter how cute he got about it (one letter ended with “G-O-T-S-A-S-T-B; Get on the stick and send the booze”) that was one thing she would not do.

W

HEN

C

LARK

W

ELCH

took command of Delta Company on the beach at Vung Tau, it meant that officers who came over on the ship would find different assignments at Lai Khe. To Lieutenant Grady it seemed at first almost like Fort Lewis all over again, with no one knowing quite what to do with him except show him a bed. He stood around the Black Lions headquarters until nightfall, and then it washed over him how different this was from any place he had been. Staring into the darkness, knowing nothing about what was out there, he grew anxious and wondered to himself,

Where are the bad guys?

Nearby, under mosquito netting, Captain George sat on his bunk and wrote home that he had found a weapon and “the nearest bunker to get in” if they got hit. The next morning at five Grady and George were awakened by the sound of artillery.

What’s going on?

Grady asked.

Wakeup rounds,

he was told. H and I firings—harassing and interdiction—which involved having the big guns fire into the countryside at predetermined spots without knowing whether enemy or water buffalo were roaming around out there. H and I’s were popular at Lai Khe and other American base camps, so much so that they would soon become an issue with the generals in Saigon, who were catching flak from the Pentagon for spending too much money on ammunition.

On the second day in camp Grady was getting ready to attend combat indoctrination school, and looking forward to a gradual transition to his new workplace, when he and George were told to hop on a supply helicopter and join the battalion command and two companies out in the field near Phu Loi. Grady had his new assignment, S-2 for the battalion, which meant chief intelligence officer. Looking back on that posting with his self-deprecating humor, he would call himself “the worst intelligence officer in the history of the U.S. Army,” which he certainly was not, but he was on the mark when he called himself “green as grass” and “an intelligence officer who didn’t know a thing.” That was part of the reality of the United States Army in Vietnam in the summer of 1967, when men were pouring in faster than seasoned officers could be found to lead them, a situation greatly exacerbated by the Pentagon policy of rotating not only enlisted men but officers out of Vietnam after twelve months. Grady was fortunate that as soon as he reached the field that day, he ran into Big Jim Shelton, the battalion’s S-3, or operations officer, a former football lineman at the University of Delaware who had been in Vietnam only a few weeks himself but radiated confidence and could outtalk anyone in the division. “Look, you work for me, and this is what you do,” Shelton began, and Grady was more than glad to listen.

While Grady stayed back at the night defensive position (NDP) that afternoon, George went with the two companies and command unit on a search-and-destroy mission, which proved uneventful, though the day did not. When they returned from the march, the battalion commander directed George to go tell the Alpha Company commander to pack his gear and report back to headquarters, he was being fired and replaced by George. “The commander I’m replacing has only had the company for four weeks and is being relieved, so I really hope I can cut it and put the co. squared away,” George wrote home to his wife. Serving as a battalion or company commander in the Big Red One during the Vietnam years was a hardship unto itself, the more dangerous equivalent of trying to manage the New York Yankees under George Steinbrenner during the early years of his ownership. Officers were constantly being moved and fired. In eight months, since the beginning of 1967, the Black Lions had already been through three battalion commanders, three Headquarters Company commanders, three Alpha commanders, three Bravo commanders, and two Charlie Company commanders. It was, said Jim Shelton, “the ass-chewingest place you’ve ever seen.” In any case, George thought the Alpha commander hardly seemed surprised, as though “he knew that the axe was coming.”

The surprise came a few hours later, when a squad of Viet Cong guerrillas slipped past the listening post and the ambush squad and launched a surprise attack on the NDP with machine gun fire and claymore mines, killing one soldier, who had been sitting atop his bunker rather than inside it, and wounding eight others. It was George’s first test. “Well, I earned my CIB (combat infantry badge),” he wrote afterward. “I assumed command of the company at 1900 and at 2200 had an attack…. It was really something. I coulda reached out and touched the live tracer rounds. Thank God I didn’t freeze and was able to make the right decisions. We had a dust off (med evac) which was hairy. I conducted it and had to help the wounded to the copter. The company did OK. The battalion CO was there but didn’t do much.”

The next morning the field operation was moved to a new location north of old Dog Leg Village. It was a dispiriting day, with soldiers exhausted, stung and angered by the surprise attack, the ground a mess of mud, a monsoon rain drenching them, and in the midst of this scene here came Major General John Hancock Hay Jr., the division boss, who swiftly fired the battalion commander. Two officers canned in two days. The resupply helicopter that night brought in the next leader of the Black Lions. He was a thirty-seven-year-old West Point graduate named Terry Allen Jr., who had served briefly as the battalion’s operations officer earlier in his tour. “He should be real good,” Clark Welch wrote to Lacy. Allen was steady and appeared seasoned. He had been in Vietnam five months by then, minus an emergency leave in June when he had returned to his native El Paso to heal an unexpected wound.

Chapter 4

El Paso, Texas

E

L

P

ASO,

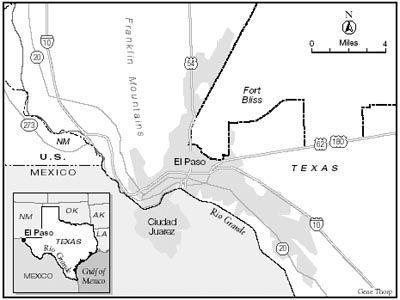

on the verge of a boom, had a population of three hundred thousand in 1967, about a third of its census count at the end of the century, but it remained a small town in the more traditional sense, a place where the surnames were familiar, where families were defined by their histories, and where everyone in the same social set, especially the established Anglos who ran the banks, businesses, and government, seemed to know or want to know everything about everyone else. There were secrets, undoubtedly—small towns incubate secrets—but the secrets were not always as private as their originators assumed; often they were known but unspoken as part of the cultural code. El Paso took its name as the place where the Rocky Mountains parted, offering an easy valley pass from east to west. The culture of the town was a curious mix of order and disorder, shaped as it was by the Rio Grande, which ran along its southern border, separating it from Ciudad Juarez, its exotic big-sister city in Mexico, and by Fort Bliss, the U.S. Army base that sprawled across a million acres of barren beige landscape to the northeast. Sitting in the basin of the Chihuahuan desert, El Paso thought of itself as the city of the sun. It boasted of more than three hundred days of sunshine a year. Its baseball team then was the Sun Kings. Its football stadium was the Sun Bowl. Its annual Sun Carnival was ruled by the beauty of a Sun Queen and her court. All of this was enough to send some people looking for places in the dark.

In from the above-ninety heat of the sun on a mid-June afternoon that year, Genevieve Coonly picked up her ringing telephone and shrieked with surprise as soon as she heard the first words from the caller.

Hello, Bebe.

It was the unmistakable voice of Terry Allen Jr., who was not only her nephew-in-law but also one of her and her husband, Bill’s, closest friends. What was he doing home? It had been only a few months since family and friends had gathered in Hart Ponder’s backyard for the farewell party when Terry left for Vietnam, and now he was back even though he had been scheduled to be gone for at least a year. Bill Coonly jokingly accused his wife of “getting out the fatted calf for the favorite son” as she prepared a luncheon feast for their surprise visitor, who had asked if he could stop by to talk. But as soon as he arrived, it was obvious that he was in no mood to eat heartily or laugh about old times.

He had come home from Vietnam, Terry Allen said, because his wife, Jean Ponder Allen, the daughter of Bebe’s sister, had written him a letter announcing that she was disillusioned with him and the military and the war and had left him for another man. This other man, literally a clown—Terry had heard that he was a rodeo clown who had appeared on the local television station where Jean worked—had moved into the Allen house and was living there on Timberwolf Drive with Jean and his three little girls while he was fighting for his country on the other side of the world. Terry hoped to save the marriage, but was unsure about the prospects. He thought that his mother and father, who lived in El Paso, were unaware of the scandal, so he did not want to stay with them. The Coonlys invited him to sleep in a guest bedroom at their double-winged ranch house in the upper valley while he tried to work things out with Jean, and they lent him one of their old cars for the week, a pink Cadillac.

The sudden way his life had veered off track left Allen disoriented. Not so long ago it had seemed that things were perfect, he said. His mother’s family, the Robinsons, and Jean’s family, the Ponders, had known one another for decades, two branches of the El Paso establishment with former mayors on both sides. The fact that Jean was thirteen years younger than he was had never given him reason for concern. How could it, when there was a twenty-year gap in the ages of his own parents, the retired general and Mary Frances, who had precisely the sort of marriage he sought to emulate? His life had followed a straight and clear path from childhood, but now here he was, out of place in his hometown, confused and lost. The first time he got behind the wheel of the pink Caddy, he drove through the streets until he ran out of gas.