Third Reich Victorious (18 page)

Zhukov planned on opening the land campaign by dropping two airborne corps behind the German lines to seize vital crossings across the Vistula River. In the north the 4th Airborne Corps’ 7th and 8th Airborne Brigades would seize crossings near Modlin, northwest of Warsaw, in support of the Western Front. In the south, the 1st Airborne Corps’ 204th and 211th Airborne Brigades would seize crossings in the vicinity of Deblin, northwest of Lublin, in support of the Southwestern Front. A second lift would bring in the 214th Airborne Brigade in the north and the 1st Airborne Brigade in the south, completing the delivery of 21,000 Red Army paratroopers and seventy-two artillery pieces and antitank guns. Both objectives were forty-five miles behind the front lines, and the General Staff had allocated one to two days for the fronts’ mobile groups to break through the German line and link up with the paratroopers.

25

At first all went well. The bulk of the aircraft had taken off and formed up without incident in the darkness. As both formations began to cross the Soviet-Polish border, however, several Red Army antiaircraft batteries opened up on the transport squadrons overhead. These opening bursts triggered a crescendo of sympathetic fire from other inexperienced and fatigued Soviet gunners all along the line. Within minutes every Red Army antiaircraft weapon along the border had joined in. Russian air defense officers could do nothing to stop the massacre. They watched horrified as dozens of troop transports, savaged by the intense fire, broke into flames and spiraled out of control, crashing to the earth. Alerted by their opponents, the German gunners joined the slaughter. The Soviet transport pilots broke formation, careening into each other and dumping paratroopers everywhere. A number attempted to turn around and return to their bases, convinced that it was suicidal to proceed.

26

Some were “persuaded” to press on, however, by pistol-wielding airborne officers who threatened to shoot them if they did not continue with their mission.

Fully a third of the airborne force, however, had been lost before even crossing the border. The rest were hopelessly scattered, and easy pickings for the eagles of the Luftwaffe. The operation in shambles, Zhukov ordered the commanders and crews of the responsible air defense divisions shot, along with any pilots who returned to their bases without dropping their men. He also postponed the launching of the second wave. “To make an omelette you must break some eggs,” Stalin remarked matter-of-factly when notified. “Keep me informed.”

At 0600, after almost three hours of preparatory artillery fires, Zhukov gave the order to begin the attack, sending in four armies of the first echelon. Reconnaissance elements and forward detachments from each army, corps, and division crossed the Bug River against surprisingly light resistance. Swarms of amphibious and light tanks were spreading out on the opposite bank and pushing rapidly westward, while engineers struggled to repair and rebuild damaged bridges for the heavier tanks. Behind them came the first wave of BT-5 and BT-7 fast tanks. “

Vperyod!

” (Forward!) was the order of the day, as the red horde raced toward the Vistula. The first reports indicated that the left bank was clear, the Germans having abandoned their positions along the Bug River sometime before the beginning of the Soviet artillery barrage. “

Nemsti ushli! My Pobedali!

” (The Germans have left! We have won!) echoed over every radio, and the tank commanders, throwing caution to the wind, ordered the units onward at even greater speed.

“Find them!” demanded an angry and not so confident Zhukov of his front commanders. “Get your forces across the river and to the Vistula as quickly as possible! And watch out for tricks!” It was, however, easier said than done. At that moment Luftwaffe attacks along the entire front caught the Red Army divisions massing on the east bank, savaging the struggling engineers and their bridges as well as the trucks and artillery of the first infantry and motorized formations waiting to cross. Hitler’s eagles had caught Zhukov by surprise. The bulk of the Red Air Force units, returning from their first missions, were refueling and rearming at their own air bases. By the time the first squadrons responded, the Germans had already inflicted significant damage on the Red Army’s lead echelons.

Traveling at top speed, the forward elements of both fronts covered fifteen miles in the first hour, leaving dozens of broken-down vehicles behind them. They found the enemy, or rather the enemy found them, in another hour. The light tanks began to explode, one after the other in rapid succession. First to go were the Soviet command tanks, with their radios and telltale multiple antennas. Having outrun their artillery and with no air support, frustrated commanders ordered their units forward in a mass rush to seize the hills and villages from which the fire was coming. More often than not, the Russians would take their objectives after the loss of dozens of vehicles, only to find the Germans had fallen back to engage them from another village or group of hills a thousand or so yards away. The fire was devastating and the advance began to slow and then to stall. Reports to the rear only brought admonitions and the same order: “Keep moving! Find the German main defensive line!” And so they had kept moving slowly and warily toward the Vistula, losing tanks to the deadly enemy fire throughout the day. The greatly depleted Soviet formations were still some distance from the river when they found the German line. Heavy antitank and antiaircraft guns decimated their ranks repeatedly. Roaming German tanks, firing from both flanks, finished off all those that tried to run away over the next several hours.

“Stalin has sown the wind,” announced Hitler, assessing the latest OKW (Armed Forces High Command) situation map at his headquarters in East Prussia. “Let him reap the whirlwind.” He nodded to Keitel, a worn copy of the 1936 edition of Count Alfred von Schlieffen’s

Cannae

tightly clutched in his hands.

27

Within minutes the necessary orders were flying over the airwaves to the commanders in the field: “Commence Whirlwind.”

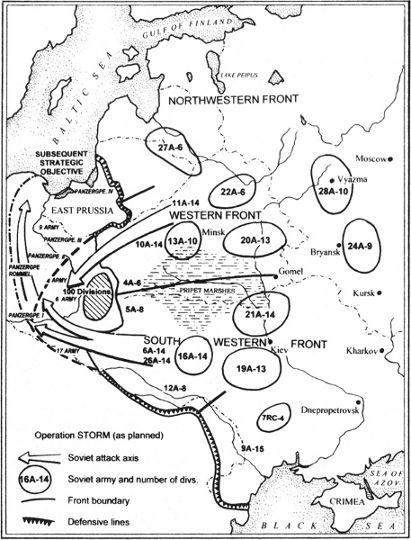

Map 5. Operation Storm

Field Marshal Ritter von Leeb’s Army Group North attacked at 0900 on July 6, three hours after the beginning of the Soviet attack, with a heavily reinforced 4th Panzer Group and XLI Motorized Corps in the lead. Von Leeb was confident that his six corps and thirty divisions would advance rapidly toward Estonia and Leningrad, smashing the Russian armies in his way. The preparatory artillery strike along a 140-mile front lasted only several minutes. Then the infantrymen and engineers rose up out of their shelters and began their assault. Overhead, almost 400 aircraft of Luftflotte 1 headed for Soviet strong points, airfields, and lines of communications. The Russians had been caught off balance, and in the first hours of the operation von Leeb’s forces reached deep inside Soviet territory, with Col. Gen. Erich Höppner’s 4th Panzer Group slicing its way through the lead elements of the Soviet 8th Army.

28

In the center, Col. Gen. Hermann Hoth’s 3rd Panzer Group flung itself across the border following an intense one-hour artillery barrage. In the first major tank battle of the war, the XXXIV Motorized Corps collided head on with General Kurkin’s 3rd Mechanized Corps in a classic meeting engagement.

The historian of the 7th Panzer Division, which took the brunt of the attack, described the scene:

The KV-1 and KV-2 46-ton tanks raged forward! Our company opened fire at 800 meters: it had no effect. The enemy advanced closer and closer without flagging. After a short time they were 50 to 100 meters in front of us. A furious fight ensued without any noticeable German success. The Russian tanks advanced further. All of our antitank shells bounced off them … The Russian tanks rolled through the ranks of the 25th Panzer Regiment and into our rear. The Panzer regiment turned about and moved to high ground.

29

The tankers of Kurkin’s corps advanced unhindered by the German fire, slowing only long enough to crush the antitank guns and their gunners beneath their tracks before speeding off to wreak havoc on the artillery positions farther to the rear. Joint action by the Panzer Ills and IVs of the 27th Panzer Division and the 20th Motorized Division, reinforced with 88mm guns, stopped the Russians dead in their tracks, inflicting heavy losses. The remainder of the German corps deployed to encircle the Soviet corps and complete its destruction. The first phase of the operation thus opened well for the Germans.

The brainchild of Adolf Hitler, Whirlwind sought the complete destruction of the Red Army in Poland and the western Soviet Union. “Let us show Stalin how the German Army conducts a real Cannae,” he had remarked to his staff, ordering the drafting of a Barbarossa variant. High altitude reconnaissance photographs had revealed a concentration of mechanized corps to the north and south of Army Groups Center and South, and Hitler had correctly surmised that the Red Army sought to destroy Wehrmacht forces in Poland. Whirlwind called for Army Group North to attack on the morning of July 6 to desynchronize Stalin’s plan by shattering the Russian Northwestern and threatening the northern flank of the Western Military District. In the meantime, the rest of the German Army would fall back to more defensible terrain near the Vistula River, luring the Red Army into eastern Poland, where it would first be ground down by defensive fires and then annihilated by a counterstroke.

In the north, Army Group Center’s 9th Army, commanded by Col. Gen. Adolf Strauss, defended from Allenstein to the northern bank of the Vistula near Warsaw, while 3rd Panzer Group conducted a spoiling attack against the Soviet 11th Army. In the center, Field Marshal Gunther von Kluge’s 4th Army held a sector from Warsaw to Deblin with Col. Gen. Heinz Guderian’s 2nd Panzer Group in reserve. At the same time, Army Group South’s 6th Army, commanded by Field Marshal Walter von Reichenau, defended from Deblin to Sandomierz with Col. Gen. Ewald von Kleist’s 1st Panzer Group in reserve. Finally, Gen. Karl Heinrich von Stülpnagel’s 17th Army guarded a sector stretching from Sandomierz to Gorlice.

The Germans had organized their defenses in depth with three main belts. The advanced position was intended to wear down the Russians and delay their attempts to seize key terrain that might assist them in launching attacks against the main line of resistance. Anticipating the storm that was to follow and unwilling to sacrifice any troops to a static defense, the two front commanders had agreed to use Panzer formations all the way to the Bug in order to inflict greater casualties. A battle outpost line, intended to wear down the Russians further, canalize their attacks, and deceive them as to the exact location of the main defensive line, ran from roughly Ostrotchka in the north to Siedlice and Lublin in the center and Przemysl in the south. This was manned by well-entrenched motorized infantry battalions fighting from high ground and villages. They were well supported by antitank guns and heavy antiaircraft guns operating in the antitank role. Finally, the main line of resistance was organized in depth behind the Vistula. Strong mobile units from the Panzer groups were placed on the flanks and in reserve.

Map 6. Operation Whirlwind

To assist the army groups in their defensive mission, the Führer had ordered hundreds of heavy and mixed air defense batteries, with their high velocity 88mm and 105mm guns, sent from the Reich to Poland. These weapons could destroy any tank in the Soviet inventory, while the lighter guns were ideal for use against infantry and soft targets. They would also provide additional protection for Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe units against Russian air attacks. The German Army had positioned the bulk of the antiaircraft guns with their heavy antitank guns along the main line of resistance. Finally, each division had laid thousands of antitank mines between the main line of resistance and the battle outpost line.