Third Reich Victorious (14 page)

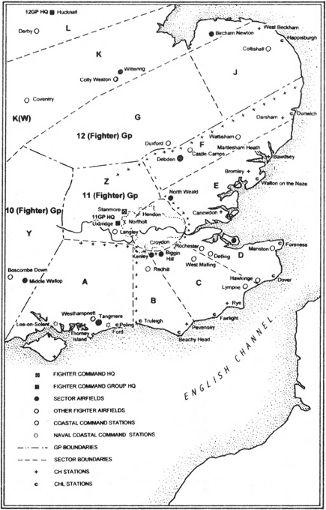

Dowding knew that unless his fighters could intercept the German aircraft before they reached their targets, the battle would be lost. This could only be done through timely warnings of attacks. Radar had the key role to play, but the information it provided on the Luftwaffe aircraft forming over northern France and beginning their flights across the Channel would only be effective if passed quickly enough to the relevant agencies. His system of direct communications between the radar stations and his own headquarters at Bentley Priory on the outskirts of London would provide such timely information, especially with the addition of the newly installed filter room. This brought coherence to the plot reports from the individual radar stations and passed results simultaneously to the Bentley Priory ops room and those at Group and Sector HQs. Dowding did not intend to run the detailed operations himself. He believed the system would work more effectively if he delegated to the group commanders. They decided which of their sectors should deal with an incoming raid and scrambled the squadrons, while the sectors controlled the fighters once they were in the air, directing them on to the enemy.

On June 22, 1940, the day Hitler presided over the French surrender ceremony in the very same railway carriage that the Allies had used to formalize the armistice that ended the fighting on the Western Front in November 1918, the Luftwaffe began more active operations against Britain. These took the form of attacks against shipping convoys in the English Channel. Their object was twofold—to demonstrate to the Royal Navy that the Channel was a “no go” area, and to draw the RAF fighters out. Ju 87s were primarily used for the attacks, with Bf 109s providing top cover. While a number of merchant vessels were sunk, the air battles themselves were little more than skirmishes, with the RAF having a slight edge in planes shot down.

On June 24, after the French signed an armistice with Italy, the Führer broadcast a speech in which he pointed out to the British that they were on their own and there was little point in carrying on the struggle. Much better that they sought peace with honor, rather than suffer needless damage and casualties. Hitler stated that if Britain made the necessary approaches within the next week, she would be granted more favorable terms than those the French had been forced to accept. If the British government ignored this generous offer, it would have to accept the consequences.

The British cabinet discussed the speech, and one or two of its members, notably Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax and former Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, were in favor of putting out feelers to establish precisely what terms Hitler was offering. But Churchill was adamant—the country must fight on; to allow itself to become a vassal of the Third Reich would be a betrayal of not just the British people, but the Empire as well. His sheer force of personality won the cabinet to his point of view. On June 25, after addressing the House of Commons, he spoke to the nation on the BBC. He dismissed the Führer’s offer out of hand, declaring that it would be a fight to the death and that Nazism would ultimately be vanquished. There was silence from Berlin, and as the skirmishes over the Channel continued, the tension grew.

The Battle of Britain began at dawn on July 2. During the night, the airfields of Luftflotten 2 and 3 in Belgium and northern France had been a hive of activity. The Luftwaffe had an ambitious program of operations. First, the bombers would take off during the hours of darkness, their objective the Group 10 and 11 airfields, which they intended to strike at first light, before the British fighters could get airborne. They would be joined by escort fighters, which would take off at dawn and then cover the bombers’ return flight. As the bombers recrossed the Channel, Ju 87s and the Me 110s of Rubensdörffer’s specialist group would strike at the Home Chain radars, concentrating on those on the English south coast. The two air fleets planned to launch two similar attacks later that day—in early afternoon and late evening—against airfields and radar stations.

Dowding’s first intimation of the impending onslaught came some twenty minutes before dawn when the filter room at Bentley Priory reported a number of groups of hostile aircraft crossing the French coast. His staff recognized that the Luftwaffe had suddenly changed its tactics, but they could not be sure of the target. Nevertheless, Groups 10, 11, and 12 reacted immediately by bringing all their squadrons to readiness. At the time, Groups 10 and 11, in the front line, were operating on the principle of having one flight per squadron on automatic dawn readiness, while the other two groups merely had one flight per airfield. In the meantime, AA guns engaged the bombers as they crossed the English coast, but with little tangible result. The bombers, organized in eight groups of some thirty planes each, flew on to their targets—seven Group 11 airfields (Westhampnett, Lympne, Tangmere, Kenley, Gravesend, West Mailing, and Biggin Hill) and Middle Wallop in Group 10’s area. They reached them as dawn broke. Simultaneously, the RAF readiness flights began to take off, but it was too late.

During the next ten minutes, the Luftwaffe aircraft bombed with impunity, dropping down to as low as 5,000 feet to ensure accuracy. They then turned for home, gaining altitude as they did so. The RAF readiness flights that did manage to get airborne set off in pursuit, but as they closed in, they were attacked by the freshly arrived Bf 109 escorts, which had the advantage of both height and sun. In the ensuing battle, the RAF came off much worse, losing twenty Spitfires and Hurricanes shot down, as against four Bf 109s, three He 111s, and a single Do 17.

As for the airfields themselves, the German bombers had caused serious damage:

Westhampnett

—runway severely cratered, one hangar destroyed, five Hurricanes destroyed on the ground (including two under repair)

Lympne

—runway damaged, huts badly damaged

Tangmere

(sector HQ)—runway rendered unusable, one hangar destroyed and one seriously damaged, six Hurricanes written off, ops room and other buildings badly damaged

Kenley

(sector HQ)—runway partially damaged, one hangar damaged, two Spitfires destroyed, administrative buildings damaged and destroyed

Gravesend

—one hangar badly damaged, two Hurricanes and two Spitfires destroyed, ops room and other buildings damaged

West Malling

—huts destroyed, much cratering

Biggin Hill

(sector HQ)—extensive damage, including to ops room, runway unusable, four Spitfires totally destroyed and several others damaged

Middle Wallop

(sector HQ)—one hangar destroyed, together with four Spitfires and three Hurricanes, some cratering to runway, and damage to administrative buildings

Map 4. Luftwaffe Assault on Group 11

Of greatest immediate concern was the damage done to Tangmere and Biggin Hill, which had a serious affect on command and control. Both had alternative ops rooms, situated outside the bases, but these were cramped and had only limited communications. The damage to runways also revealed another shortcoming in Fighter Command’s organization—limited airfield repair resources. Some airfields did have specialist Royal Engineer repair teams, but others had to rely on civilian labor. Worse, there was a serious shortage of plant equipment—three airfields (Manston, Hawkinge, and Lympne) had just one bulldozer among them. A further problem was the number of unexploded bombs. Consequently, it would take time to repair the damage, and the aircraft at bases rendered temporarily unusable had to redeploy to satellite airfields. But this lay in the future. In the meantime, while Group 11 reeled from the initial shock of this attack, it was about to be struck again.

As the bombers recrossed the English coast, groups of Ju 87s and the Me 110s of Erprobungsgruppe 210 were heading toward the coast from France. Their mission was to attack the radar stations at Ventnor on the Isle of Wight, Poling, Truleigh, Beachy Head, and Pevensey. The tall towers of the stations made them easy targets to find, but the Luftwaffe planners recognized that these were difficult to destroy. The crews were therefore directed to aim their bombs at the huts at their base. While the stations themselves identified the approaching raiders, the early airfield attacks had thrown Group 11 into confusion. All the controllers could do was try to redirect those fighters grappling with the bombers and their escorts, but only a few heeded the call. As a result, the Ju 87s and Me 110s were able to launch their attacks without interference. Erprobungsgruppe 210 was tasked with taking on Ventnor and Poling and put its specialist training to good effect. Both were extensively damaged and went off the air. The Ju 87s also succeeded in blinding the station at Beachy Head, but while they damaged the remaining two radars, these continued to function. Four Ju 87s were lost—two to antiaircraft fire and two shot down by fighters on their return flight—and one Me 110 also fell victim to the AA guns.

As the Luftwaffe crews landed back at their bases and the initial debriefings took place, it became clear that the first major German attack in the Battle of Britain had been highly successful. Hermann Göring, who had established a temporary headquarters in his personal train on the outskirts of Paris, was elated by the reports he received. He issued a special order of the day, congratulating his air crews and exhorting them to maintain the pressure—“just a few more blows like those of this morning will fatally cripple the RAF and bring Britain to its knees!”

On the airfields themselves, the ground crews labored to rearm and refuel the aircraft for the second strike of the day. While the air crews ate an alfresco meal near their planes, they were briefed for the second attack. Having begun to clear a defense-free path to London, it was the Luftwaffe’s intention both to widen it and to build on the damage already inflicted. In the meantime, small groups of Bf 109s and 110s trailed their coats over the Channel to distract the RAF.

Dowding’s most pressing immediate concerns were the gaps that now existed in his radar coverage. He ordered the deployment of mobile radar units (MRU) to cover these, but it would take some hours for them to become fully operational and they lacked the range of the static Chain Home stations. Realizing the aircraft casualties suffered by Group 11, he decided to move one Spitfire and one Hurricane squadron from Group 10. Meanwhile, Park put priority on reestablishing the communications at Tangmere and Biggin Hill. Certain that the Luftwaffe would shortly strike again, neither he nor Dowding was tempted by the German activities over the Channel.

The next wave of German attacks began to develop shortly after 1300. In spite of the holes in the radar coverage, the Bentley Priory filter room did manage to establish that the main effort was again being directed at Group 11. Park immediately scrambled his squadrons, so they would not be caught on the ground, but they were unable to intercept the bombers before they struck. Kenley, Biggin Hill, and Gravesend suffered further damage, while Manston, on the extreme eastern tip of Kent, and Croydon, suffered for the first time. Further Stuka and Me 110 attacks were made against the radar system, adding to the damage at Ventnor and Poling, and virtually destroying the radar at Foreness, close to Manston.

Nevertheless, the RAF fighters did enjoy more success than they had in the morning. Four He 111s and three Do 17s were destroyed, together with six Ju 87s—whose relatively low speed made them vulnerable to fighter attack—four Bf 109s and three Me 110s. But the Bf 109 escorts still enjoyed the advantage of height, enabling them to shoot down eight Hurricanes and six Spitfires.

Apart from further disrupting Fighter Command’s command, control, and communications, and creating additional holes in the radar coverage, this second wave of attacks caused the civilian airfield repair teams to stop work. They declared that it was too dangerous to continue. Efforts to persuade them to change their minds proved fruitless. The attack also further disrupted vital maintenance work on the RAF aircraft. The final main attack of the day took place an hour before sunset. The targets were again much the same and the casualties to both sides of the same order as the previous raid.

That night both sides took stock of the situation. The Luftwaffe leaders could be satisfied over how the day had gone. They knew that they’d weakened Fighter Command both in the air and on the ground. A clear indication of this was the inability of the British fighters to intercept the bombers before they reached their targets. It was also noticeable that there were fewer fighters in the air during the final attacks than during the lunchtime raids. While it had been a long day for the crews, both air and ground, their morale was high. Göring, Sperrle, and Kesselring all agreed that if the pressure was maintained, the British air defenses would soon crumble. In the meantime, in order to play on the nerves of the RAF, random attacks by small groups of bombers would continue throughout the hours of darkness against the airfields.