This Great Struggle (22 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

Seventy-five miles southwest of Winchester, near the village of Port Republic, Jackson turned at bay and prepared to confront his pursuers. Freémont’s troops were advancing from the north, McDowell’s from the northeast. By controlling key bridges Jackson used two small rivers to keep his two enemies apart. On June 8 a portion of Ewell’s division met Freémont’s command in a blocking action at Cross Keys. Though Freémont outnumbered Ewell two to one, he advanced so tentatively that little serious fighting occurred. By nightfall Jackson felt confident that he had little to fear from Freémont and could bring all but a token force of Ewell’s division over to Port Republic for his planned showdown with McDowell’s lead division under Jackson’s old Kernstown nemesis Shields.

On June 8, one month to the day after the Battle of McDowell, Jackson and Shields fought the Battle of Port Republic. Though a wizard of operational maneuver as he had just demonstrated over the course of the preceding month, Jackson was not always adept in tactics. He certainly did poorly in this battle, committing his troops piecemeal and without adequate reconnaissance. Troops on both sides fought hard. In the end, Jackson had more men available than did Shields and was able to force the Federals back. In this narrow victory, Jackson lost eight hundred men and Shields about one thousand.

The Battle of Port Republic marked the end of what was to become famous as Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign, an operational masterpiece still studied by students of the art of war. Jackson’s eighteen thousand men had marched hundreds of miles. Through excellent knowledge of the terrain, good intelligence of enemy strength and movements, and Jackson’s ability to grasp quickly and accurately the operational situation and how he could make the most of it, his small army had defeated three separate enemy armies whose combined numbers totaled fifty-five thousand men. The strategic importance of the campaign lay in the fact that it had kept McDowell’s command and possibly additional Union troops away from McClellan for several vital weeks.

FROM SEVEN PINES TO THE SEVEN DAYS

By the time Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign was at its height, McClellan’s troops had reached the outskirts of Richmond. Union soldiers could see the spires of the Confederate capital’s churches and hear its public clocks strike the hours. Davis seethed with anger at Johnston for his retreat into the very suburbs of the capital without giving battle to the enemy. To make matters worse, Johnston had not kept Davis apprised of his activities or plans. Like his old friend from prewar army days, George McClellan, he seemed to feel that the commander in chief had no right to know what the army was doing and what its commander planned. The president had ridden out to inspect the lines daily, much to Johnston’s annoyance, and on one occasion would have ridden inadvertently right into Union lines had not Confederate soldiers flagged him down and warned him that, because of a retreat the previous evening of which Johnston had given him no word before or after the fact, he was actually about to proceed beyond the new Confederate lines. Davis applied heavy pressure on Johnston to persuade him not to give up Richmond without a fight. According to one account, Davis threatened that if Johnston would not fight for Richmond, he, Davis, would find a general who would.

At any rate, Johnston planned a May 31 attack on McClellan in which he hoped to take advantage of an important terrain feature near Richmond. Cutting across McClellan’s position was a tributary of the James called the Chickahominy. Its valley amounted to a broad belt of swamp that troops, guns, caissons, and supply wagons could cross only with the utmost difficulty. The Chickahominy was particularly inconveniently located for McClellan since Richmond was on the south side of the Chickahominy but McClellan’s supply line ran back to his right rear, on the north side of the swampy little river. That meant that in order to protect his supply line the Union general had to maintain a substantial force north of the Chickahominy and that in order to attack Richmond he had to place a large force south of that stream. Johnston planned to take advantage of that division of force by massing his own troops against the half of the Army of the Potomac that was south of the Chickahominy, betting that the difficult crossing of the swampy Chickahominy bottoms would prevent the other half of McClellan’s army from coming to the aid of their comrades.

It was as good a plan as any he could have come up with, but its execution by the Confederate army was atrocious. Johnston assigned a key role in the assault to his senior division commander, James Longstreet, a man whose very demeanor seemed to inspire confidence among all those around him. Unfortunately Longstreet was headstrong and ambitious. Seeing that Johnston’s plan called for him to attack under Johnston’s direct supervision, he decided instead to shift his division to another part of the front where he could have independence. The movement threw the army into disarray and delayed the start of the attack for many hours. When it did go in, the attack was a confused mess. Late in the day Johnston rode to the front to try to sort it out and within the space of a few seconds was struck both by an enemy rifle bullet and by a shell fragment and carried off the field badly wounded. The Yankees would call this battle Fair Oaks after a location on the battlefield where their troops had done well. The Confederates would call it Seven Pines for similar reasons.

Davis and Lee had made the disturbingly short ride from Richmond to see the day’s fighting. After Johnston’s wounding, Davis looked up the army’s second in command, Major General Gustavus W. Smith (West Point, 1842), but was dismayed to find him not at all posted on Johnston’s plans and completely unequal to the occasion. As Davis and Lee rode together back into Richmond that evening, the president apparently reflected on the fact that the army would need a new commander. Its second in command was inadequate, and its third-ranking officer, Longstreet, had just turned in a dismal performance. Yet the commander would have to be someone then present in the Richmond area since the army, with its back to the capital and a victorious enemy in front, would need his direction immediately. Turning to his companion, Davis announced that he would assign Lee to command of the army.

Lee took command the following day. Over the weeks that followed he went to work to get it back into fighting shape and put his stamp on it. He encouraged officers not to count battles as already lost on the basis of their inferior numbers but to apply themselves to overcoming such difficulties. In an apparent hint at where he planned to take the war, he named his new command the Army of Northern Virginia. By late June he was ready to launch an offensive of his own—and none too soon since McClellan had been edging ever deeper into the outskirts of Richmond and had to be turned back if the capital was to be saved.

Lee’s plan was even more daring than Johnston’s. McClellan had by this time increased the number of corps in his army to six by taking divisions from the Second, Third, and Fourth corps and using them to form the Fifth and Sixth corps for two of his personal favorites, Major General Fitz John Porter (West Point, 1845), who got the Fifth Corps, and Major General William B. Franklin (West Point, 1843), who got the Sixth. As the Army of the Potomac had edged closer to Richmond over the past month, more and more of the army had moved over to the south bank until only a single corps, the Fifth, remained on the north bank to cover the army’s supply line, the Richmond & York River Railroad. That corps was Lee’s target. He planned to reduce the Confederate defenders immediately in front of Richmond, facing McClellan’s other four corps, to a bare minimum and mass almost all of his army, which would be reinforced by the addition of Jackson’s command hastily summoned from the Shenandoah Valley immediately after the completion of its dramatic campaign there, against Porter’s Fifth Corps near the hamlet of Mechanicsville. Davis was skeptical, but Lee won him over.

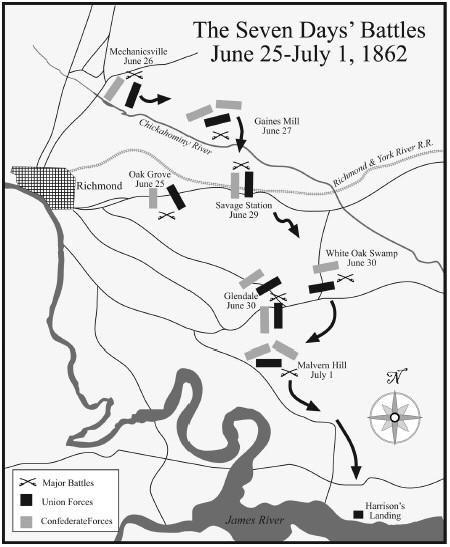

He planned to launch his attack at Mechanicsville on June 26. He got a scare when McClellan made a relatively minor push against the Richmond defenses on the twenty-fifth, but McClellan’s push was a small affair aimed merely at seizing a few more yards of ground. Right on schedule, Lee opened his grand offensive the following day, with Davis and his staff on hand to observe. It was almost as bad a fiasco as Seven Pines. Jackson was supposed to open the offensive with an attack on Porter’s exposed right flank, but the hero of Manassas and the valley inexplicably failed to get his troops into position. In Lee’s center, division commander Ambrose Powell Hill, West Point classmate of McClellan and unsuccessful suitor for the hand of the present Mrs. McClellan, got tired of waiting and launched his division straight against the entrenched Union defenders. This was the signal for the rest of Lee’s army to join the assault, which it did. The result was a bloody repulse. Confederate losses were almost 1,500, while the Federals lost fewer than four hundred.

If Lee had chanced to take a stray bullet and had died at Mechanicsville, he would have been counted as great a failure as Albert Sidney Johnston, but he survived and took up the offensive again the next day. Despite the Union victory on the twenty-sixth, McClellan was thoroughly cowed, convinced as usual that he was outnumbered at least two to one no matter how many men he had. He decided it would be impossible to defend the Richmond & York River Railroad and that his only chance was to abandon it, march his army back and across the peninsula, and take up a new base of supplies at Harrison’s Landing on the James River, now available since the

Virginia

’s demise. McClellan called the resulting movement, which took his army thirty miles farther away from Richmond, a “change of base.” The rest of the world called it a retreat. McClellan ordered Porter to fall back five miles to a position at Gaines’ Mill and there hold the Rebels one more day before retiring to the south bank of the Chickahominy and joining the rest of the army in its movement southeastward across the peninsula.

On the morning of June 27, Lee followed up the retreating Fifth Corps and found it in a stronger defensive position at Gaines’ Mill. Again Jackson failed to come up to scratch, and again the rest of Lee’s army hurled itself against the Union defenses. The result was even bloodier than the day before, but Lee had most of his army on hand, giving him a heavy numerical advantage over Porter. Late in the day a brigade of Texans led by John Bell Hood (West Point, 1853) finally broke through the Union line, which then collapsed like a breached levee. A division of the Sixth Corps and one of the Second moved across the Chickahominy to help cover Porter’s retreat, aided by approaching darkness, but the rest of McClellan’s army remained idle on the south bank of the Chickahominy, convinced by Confederate bluffing that the small screen of Rebels between them and Richmond was in fact a mighty host about to fall on them. Confederate casualties at Gaines’ Mill numbered almost eight thousand. Union losses in killed and wounded numbered scarcely half that many, though another 2,800 Federals were captured or missing in the confused twilight retreat.

For the next four days, Lee, with an army only slightly smaller than McClellan’s, tried again and again to cut off the Federals’ path of retreat across and down the peninsula. Had he succeeded, he might have bagged the Army of the Potomac almost entirely, but he was plagued by poor or nonexistent staff work and had great difficulty getting his orders transmitted and carried out. Jackson continued in some strange sort of funk, and historians still argue about the nature and cause of his dysfunction that week. Extreme fatigue is as good a guess as any. Forced marches throughout the Shenandoah Valley and then on the way to Richmond probably exhausted Jackson. McClellan provided almost no instructions for his retreating army, busying himself with affairs well to the rear, preparation of the new supply base, and the like. His corps commanders coordinated the rearguard actions as best they could, and the troops fought stoutly on each occasion. Every day saw another battle. June 30 brought the climatic Battle of Glendale, as Lee’s troops contended for a key crossroads whose possession would allow them to cut off the retreat of a major portion of the Army of the Potomac. Once again the combat was intense and lasted into the dusk. Casualties were about four thousand on each side, and the Federals succeeded in holding the vital crossroads.

Frustrated at his inability to trap McClellan in nearly a week of fighting, Lee on July 1 launched his army in another all-out frontal assault. This time the Army of the Potomac was arrayed along the military crest of gently sloping Malvern Hill, where massed Union artillery commanded a splendid field of fire. Again deficient staff work impaired Lee’s control of his army. A Confederate attempt at a preliminary artillery barrage was a disaster, as well-aimed Union salvos silenced the Rebel batteries almost as quickly as they wheeled into position and opened fire. The infantry assault should have been canceled but went in anyway, with predictable results. When it was over more than five thousand Confederates lay scattered across the gentle, grassy slope. A Union officer surveying the field the next morning noted that “enough of them were alive and moving to give the field a singular crawling effect.”

1