This Great Struggle (20 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

The Virginia iteration of the Great Valley of the Appalachians, the Shenandoah Valley comprised during the Civil War a curious feature of Virginia geography and culture. Bounded on the east by the Blue Ridge, on the west by the Alleghenies, and on the north by the Potomac, the Shenandoah was the breadbasket of Virginia, a land of agricultural plenty, faithfully maintained by thrifty, industrious farmers, many of whom were members of a pacifist German brethren sect who had migrated down the Great Valley from Pennsylvania. They gathered on Sunday mornings in plain, unadorned houses of worship, without steeples, and their insistence on baptism by immersion had led irreverent neighbors to nickname them Dunkers. Naturally the valley also had its share of Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians. It had fewer slaves than the rest of Virginia but was generally still committed to the twin causes of slavery and the Confederacy.

The valley had hitherto been a backwater of the war. In 1859 John Brown had done his part to help trigger the war at Harpers Ferry, at the extreme lower end of the valley (in the Shenandoah Valley, “lower” referred to the direction of the Shenandoah River, which flows generally southwest to northeast). Later Johnston had given Patterson the slip in the valley to get his troops to Manassas in time to help win the Battle of Bull Run. So far the valley had seen only minor fighting.

Now Jackson’s orders from Johnston directed him to take action to prevent the Yankees from sending any more troops from northern Virginia down to the peninsula. Believing the area reasonably well pacified, Union commanders were indeed pulling units away to add to McClellan’s massive army taking ship for the Chesapeake. In late March, Jackson got word that the Federals had pulled most of their troops out of the village of Kernstown, near Winchester in the lower valley, about thirty miles from Harpers Ferry. Supposedly only a small Union rear guard remained at Kernstown, and Jackson decided that the situation offered him the perfect opportunity to carry out his orders by attacking and destroying the Union outpost there, forcing the Federals to halt their movement toward the peninsula and turn back to deal with him.

Jackson struck on March 23, but he was in for a surprise. His information had been wrong, and the Federals in Kernstown numbered nine thousand men under the command of Mexican War veteran Brigadier General James Shields. Jackson’s badly outnumbered troops put up a game fight, but they had no chance of winning, and Stonewall had to retreat, something he very much disliked doing but had to continue for most of the rest of the month, falling back far up the valley. Despite the drubbing he had taken from Shields, Jackson had nevertheless succeeded in accomplishing his strategic goal. His aggressiveness at Kernstown convinced Lincoln that more troops were needed in that sector. He halted the movement of troops out of the Shenandoah, ordered others back to the valley, and began to contemplate anew the potential vulnerability of Washington.

As more and more units of McClellan’s vast army arrived on the peninsula, it became increasingly obvious that the Federals were preparing a major campaign toward Richmond from that direction. McClellan may not have been the war’s most aggressive general, but his strategic vision, in a narrowly military sense that ignored political realities, was nevertheless excellent. The presence of his army on the peninsula posed a desperate threat to the Confederate capital. Standing between McClellan and Richmond were about fifteen thousand Confederate soldiers under the command of Major General John B. Magruder (West Point, 1830). McClellan seemed the only military man in Virginia that spring who did not see that his massive army could have run over Magruder’s corporal’s guard any time it chose to do so. Magruder certainly saw it and frequently reminded the Richmond authorities of his—and their—danger.

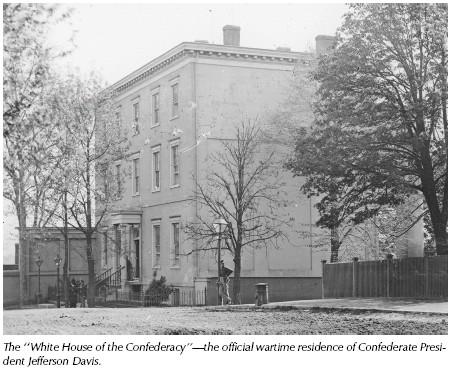

Davis needed little reminder. On March 27 he called a conference at his residence, Richmond’s Brockenbrough Mansion, so that he, Lee, Johnston, and current Secretary of War (the Confederacy’s third) George W. Randolph could discuss the Confederacy’s proper response to the threat. Of the four main participants in the conference, only Davis was not a Virginian. The discussion continued throughout the day and late into the night, sometimes growing passionate. Johnston believed that the correct policy was to withdraw Confederate forces all the way up the peninsula, virtually to the gates of Richmond, and there throw every soldier the Confederacy could possibly spare into a showdown battle while the enemy was as far as possible from his base of supplies at the foot of the peninsula.

Lee sensed in Johnston’s proposal a willingness not only to retreat but also to give up Richmond in the name of saving his army. Lee disagreed vehemently, arguing correctly that Richmond must be held and that the place to do so was as far down the peninsula as possible. Beginning the process of stopping the enemy there would open the possibility for potential counter-strokes as the Federals worked their way slowly toward the Confederate capital. Davis had to consider that coming on the heels of a winter and spring of Confederate disasters from the Atlantic coast to the Tennessee River, the loss of Richmond might demoralize southern whites to the point of giving up the fight. Whatever his thinking, Davis sided with Lee and ordered Johnston to take his army to the peninsula and join Magruder near Yorktown, where a line of Confederate entrenchments spanned the peninsula, and there contest every foot of ground with McClellan as the latter began his expected advance. Johnston returned sullenly to his command. As he later confessed, he had already made up his mind to retreat fairly rapidly up the peninsula and thus force his policy rather than Lee’s on an unwilling Davis.

McClellan and most of his army were on the peninsula and preparing to advance by the beginning of April, but McClellan still had himself convinced that he was up against twice his numbers of Rebels. Where the Confederates would conceivably have found that many troops is a riddle to which Jefferson Davis would undoubtedly have liked to know the answer. Nevertheless McClellan remained convinced that only his superior skill could overcome the Rebel hordes and therefore that he must be very careful. His state of mind grew worse when on April 3 Lincoln informed him by dispatch from Washington that he had decided to withhold one of the four corps of the Army of the Potomac, McDowell’s First Corps, for the protection of Washington.

Back when Lincoln had first approved the Urbanna plan, he had asked the generals what would be the minimum number of troops necessary to ensure the safety of Washington, and they had given him a figure. Lincoln had then stipulated to McClellan that that number of men needed to be in and around the capital. McClellan had agreed but had included in his count troops stationed in places like the Shenandoah Valley. They did perform a certain function for the protection of the capital, but they were not what Lincoln and the generals had had in mind. When Lincoln learned of McClellan’s creative bookkeeping with troop strengths, he had decided to detach McDowell so as to make up the necessary minimum protection for Washington.

McClellan was already bitter about what he conceived as Lincoln’s non-support and interference with his campaign, and this event made him more so. Ever afterward McClellan, along with his defenders down to the present day, argued that the loss of McDowell’s forty thousand men was the undoing of the Peninsula Campaign. If not for that, Little Mac would insist, Richmond would have fallen and the war ended. To be sure, Davis, Lee, and other top Confederates dreaded the possibility that McDowell’s command would join McClellan and rejoiced to see that it was staying in northern Virginia. Whether McClellan could actually have supplied an army as big as he would have had with McDowell’s troops on the peninsula is open to question. As the campaign developed, the little more than one hundred thousand men whom McClellan did have there taxed the ability of his supply personnel and the single-track Richmond & York River Railroad to the utmost. Aside from that, as Lincoln was to learn to his sorrow, McClellan’s invariable habit was to respond to reinforcements by claiming that his opponent had just received twice as many men and that he therefore was still unable to accomplish anything.

Two days later, on April 5, McClellan’s grand army arrived in front of Magruder’s Yorktown defenses. Johnston’s troops were still not in the lines, and McClellan had the opportunity by an aggressive assault to sweep the defenders aside and drive into Richmond before Johnston or anyone else could stop him. That was not McClellan’s way of doing things. He wanted to avoid bloodshed as much as possible—among his own troops because he seemed to love the army almost too much and among the enemy because he hoped to set up a compromise peace in which the Rebels would be assuaged, after their moderate military chastisement, and slavery would be saved. For him, avoiding casualties was also a matter of conceit. He would demonstrate his superior skill by deftly taking Richmond with negligible loss of life by means of the scientific methods of siegecraft. Therefore, with more than one hundred thousand men, he settled down to besiege Magruder’s fifteen thousand men at Yorktown, and while the siege went on, Johnston’s troops arrived from the Rappahannock and filed into the Confederate trenches, closing the possibility of a quick and easy victory.

Siegecraft was as close to a science as anything in warfare and seemed to offer a high probability of success if one had the material wherewithal to apply it. Its rules were well established and would not fail unless the besieged did something unexpected. It was an exercise in military engineering, and McClellan had been an engineer officer, second in his class at West Point, where engineering was the chief component of the curriculum. Thus, day after day McClellan’s troops labored on their siege works, building the entrenched batteries from which the siege guns would pound the Rebels into submission. His numerical superiority rendered an elaborate siege unnecessary. Speed and overwhelming force would have trumped pick and shovel and allowed him to overrun the Yorktown works. Yet the safety promised by the science of siegecraft suited McClellan perfectly.

THE SIEGE OF YORKTOWN AND THE BATTLE OF WILLIAMSBURG

McClellan’s progress was slow enough to stir serious discontent in Washington, where Lincoln wrote to his general assuring him of his continuing support but warning him of political realities. “You must act,” the president admonished. Yet if the fear that McClellan would not act in timely fashion weighed heavy in one capital, the fear that he would act raised even more alarm in the other, where the danger of the Confederate situation seemed to grow by the day. By late April Lincoln had become satisfied enough with the safety of Washington to send some of McDowell’s troops to McClellan via the Chesapeake and to allow McDowell with the rest of his force to advance directly south toward Richmond with a view to linking up with McClellan on the northeastern side of the Confederate capital. That would give McClellan a numerical superiority approaching three to one.

To make matters worse for Davis, the Confederacy also faced the danger that its army would disintegrate at the moment the enemy campaign against Richmond began in earnest. One year ago when each president had called for troops, the Confederacy had enlisted its soldiers for one-year terms. That had been an advantage when Union troops enlisted for only ninety days, but now the Union army had been reborn, larger than ever, of three-year volunteers, while the terms of enlistment of the Confederates were quickly running out. Many of the troops had no intention of reenlisting, feeling that they had done their part and it was now someone else’s turn to serve in the army. Besides, war appeared less exciting from the Richmond defenses than it had at enlistment rallies back home or even in the army on the eve of First Manassas. It was an attitude that could have killed the Confederacy. Even if enough other men had been available to refill the ranks, the Confederacy could not afford to lose its experienced soldiers.