Thomas Godfrey (Ed) (90 page)

Read Thomas Godfrey (Ed) Online

Authors: Murder for Christmas

I

reached over and turned out the light beside the bed. “Oh!”

It was

Mother’s voice. I snapped the light back on. She was sitting upright in bed.

Gasping. Wheezing.

Something

was wrong. Her face was red and swollen. She was grunting and flailing her arms

toward me.

I

looked at the glass. What had happened?

She

was trying to scream but all that came out was breathy gurgling. She grabbed my

arm.

The

veins around her eyes protruded out. The eyes themselves were bulging and

bloodshot. Copious yellow mucus spilled from her mouth. The matted white curls

on her head seemed alive and writhing.

Her

grip tightened. The other arm shot out suddenly, catching the lamp beside the

bed, sending it crashing to the floor.

The

door flew open. Dr. Snavely was inside.

“Get

some adrenalin from my bag,” he yelled.

I

tried to speak but my tongue would not work.

The

nurse hurried into the room with a hypodermic. The old man grabbed it and

jabbed it into Mother’s hip.

Her

other hand was at the front of my shirt.

“It’s

all right. It’s all right,” he was shouting at both of us. “I’m going to send

her into the hospital tonight. Don’t worry. She’s going to be all right.

Somehow

I knew she would.

“What

did you give her?” he asked, looking curiously at the glass in my hand. The

glass I had planned to put in the garbage disposal.

I

heard myself give an answer, but it was like I was hearing someone else’s

voice. I could feel the glass leave my hand. I could feel her grip easing.

Something was said around me.

Then I

knew. It was just like “the penicillin shot.”

But it

couldn’t be.

It was

impossible.

Who

ever heard of anyone being allergic to poison?

Boxing

Day

Bonus

D. B. Wyndham Lewis

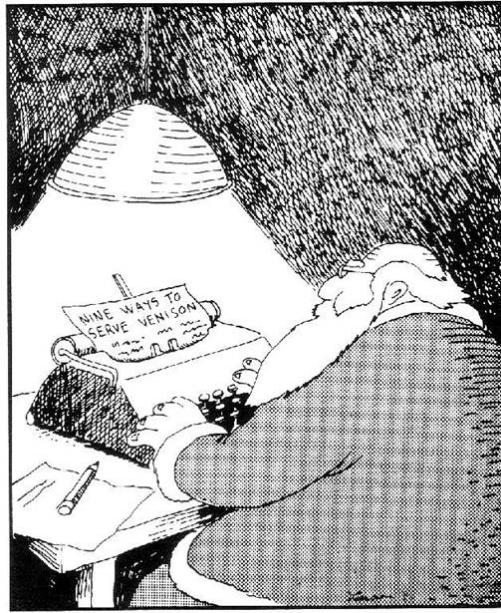

D. B. Wyndham Lewis is a name almost

unknown on this side of the Atlantic. Yet he was for years one of England’s

most celebrated wits and satirists.

He came from a prominent Welsh

family and was headed for a career in Law when he decided to try writing. His

first book was a successful biography of Francois Villon, the famous French

rogue and poet.

“Ring Out, Wild Bells” shows his

patients-taking-over-the-lunatic-asylum view of life. Here he takes aim at the

English country house school of crime fiction and hits it right between the

eyes.

Later in life he characterized

himself as “a man who deplores the decline of culture, manners and civilization

which has been going on since the Thirteenth Century, and at an accelerated

pace since the Eighteenth.” However Wyndham Lewis’s writing leads one to

believe that, if he thought civilization had been raped over the past seven

centuries, he was one of those who was secretly enjoying it.

His most famous collection is

Welcome to

All This

(1930. ) He and another

Englishman, Charles Bennett, collaborated on an original story about ordinary

people caught in an assassination plot which they later adapted for Alfred

Hitchcock’s celebrated film

The Man

Who Knew Too Much

(1934, remade 1956 )

Nothing

could be more festive than the breakfast-room at

Merryweather Hall this noontide of 29th December. On the hearth a huge

crackling fire bade defiance to the rain which lashed the tall french windows.

The panelled walls were gay with holly and mistletoe and paper decorations of

every hue. On the long sideboard were displayed eggs in conjunction with ham,

bacon, and sausages, also boiled and scrambled; kedgeree, devilled kidneys,

chops, grilled herrings, sole, and haddock, cold turkey, cold goose, cold grouse,

cold game pie, cold ham, cold beef, brawn, potted shrimps, a huge Stilton,

fruit of every kind, rolls, toast, tea, and coffee, all simmering on silver

heaters or tempting the healthy appetite from huge crested salvers. Brooding

over all this with an evil leer, the butler, Mr. Banks, looked up to see a

youngish guest with drawn and yellow face, shuddering violently.

“Breakfast,

sir?” asked Banks, rubbing his hands.

The

guest, a Mr. Reginald Parable, nodded and held out his palm. Banks shook into

it two tablets from a small bottle.

“They’re

all in the library,” said Banks, pouring half a tumbler of water. “Cor, what

they look like—well,” said Banks, chuckling, “it’s just too bad.”

Mr.

Parable finished breakfast in one swallow and went along to the library. In

every arm-chair, and lying against each other on every settee, eyes closed,

faces worn with misery, each wearing a paper cap from a cracker, lay Squire

Merryweather’s guests. The squire believed in a real old-fashioned Christmas,

and for five days now his guests had tottered, stiff with eating, from table to

chair, only to be roused by the jovial squire with a festive roar ten minutes

later.

The

countryside was under water; and as nobody could go out from morning to night,

Squire Merryweather could, and did, devise every kind of merrie old-time

entertainment for his raving guests.

Thunderous

distant chuckles as Mr. Parable wavered into the only unoccupied corner of a

huge leather settee announced that the squire had been consulting his secret

store of books of merriment once more. And even as Mr. Parable hastily turned

to feign epilepsy in his corner, Squire Merryweather bustled in.

“Morning,”

said a weak voice, that of Lord Lymph.

“Wake

all these people up,” said the squire.

When

everybody was awake the squire said: “Colonel Rollick has five daughters,

Gertrude, Mabel, Pamela, Edith, and Hilda. Mabel is half the age that Gertrude

and Edith were when Hilda and Mabel were respectively twice and one-and-a-half

times as old as Pamela will be on 8th May 1940. Wait a minute—that’s right, 8th

May. Every time the colonel takes his five daughters to town for the day it

costs him three pounds fifteen and eight-pence-halfpenny in railway fares,

first return. One Christmas night Colonel Rollick says to his guests: ‘Let’s

play rectangles.’ ‘I don’t know how it’s played,’ says old Mrs. Cheeryton, who

happens to be present. ‘Why,’ says the colonel, ‘like this: we get the

Ague-Browns to drop in, and form ourselves into four units, the square on the

hypotenuse of which is equal to the sum of the squares on the—’”

At

this point a lovely, lazy, deep-voiced blonde, Mrs. Wallaby-Threep, roused

herself sufficiently to produce a dainty pearl-handled revolver from her

corsage and fire at Squire Merryweather twice, missing him each time.

“Eh?

Who spoke?” asked the squire abruptly, without raising his eyes from

Ye Merrie Christmasse Puzzle-Booke.

“Tiny

Tim,” replied Mrs. Wallaby-Threep, taking one more shot. This time, however,

she missed as before.

“You

probably took too much of a pull on the trigger,” murmured the rector with a

deprecating smile. The squire was patron of the living and he felt a duty

towards his guests.

“I’ll

get him yet,” said Mrs. Wallaby-Threep.

“Charades!”

shouted Squire Merryweather suddenly, waving a sprig of holly in his right

hand.

“Again?”

said a querulous Old Etonian voice. It was that of Mr. Egbert Frankleigh, the

famous gentleman-novelist, who wanted to tell more stories. Since Christmas Eve

there had been five story-telling sessions, each guest supplying some tale of

romance, adventure, mystery, or plain boredom. After every story the squire had

applauded loudly and called for wassail, frumenty, old English dances, and

merry-making—even after two very peculiar stories about obsessional neuroses

told by two sombre young Oxford men, Mr. Ebbing and Mr. Crafter, both of whom

took hashish with Avocado pears, wore black suede shoes, and practised

Mithraism.

“Charades!”

roared Squire Merryweather, tucking his book under his arm and rubbing his

hands with a roar of laughter. “Hurrah! Come along, everybody. Jump to it, boys

and girls! This is going to be fun! Two of you, quick!”

A

choking snore from poor old Lady Emily Wainscot, who was quite worn out (she

died the following week, greatly regretted), was the only reply. Fourteen pairs

of lack-luster-ringed-with-blue eyes stared at him in haggard silence.

“Eh?

What?” asked the squire, more bewildered than hurt.

“You

said

charades,

sir?”

said Mr. Ebbing. “We shall be delighted to assist!”

Booming

like a happy bull, the squire flung an arm round each of the two young men and

danced them out of the room.

“Me

for the hay,” said Mrs. Wallaby-Threep, snuggling into a cushion and closing

her eyes. The rest of the company were not slow to follow suit. Very soon all

were asleep, and snoring yelps and groans filled the library of Merryweather

Hall.

* * *

It was

bright, sunshiny daylight when the banging of the gong by the second footman

roused the squire’s guests from nearly twenty-four hours of deep, refreshing

sleep. The sardonic Banks stood before them. He seemed angry, and addressed

himself to Lord Lymph.

“I

just found the squire’s body in a wardrobe trunk, my lord.”

“In a

trunk,

Banks?”

“That’s

all right,” said Lady Ura Treate, yawning. “It’s an old Oxford trick. Body in a

trunk. All these neurotics do it. Where

are

those two sweet

chaps, Banks?”

“They’ve

hopped it, my lady.”

“Well,

that’s all right, Banks,” said Freddie Slouche. “Body in trunk. Country-house mystery.

Quite normal.”

As he

spoke, the guests, chattering happily, were already streaming out to order the

packing and see to their cars. In a few moments only Banks and Mr. Parable were

left in the room. Banks seemed aggrieved.

“It’s

all pretty dam fine, Mr. Whoosis, but who gets it in the neck when the cops get

down? Who’ll be under suspicion as per usual? Who always is? The butler! Me!”

“Just

an occupational risk,” said Mr. Parable, politely.

“It

would be if I wasn’t a bit smart,” said Banks.

Mr.

Parable nodded and hurried out as the servants began looting the hall.