Three Good Things

h

r

e

e

G

o

o

d

T

h

i

n

g

s

L

o

i

s

P

e

t

e

r

s

o

n

o

rca

currents

O

R

C

A

B

O

O

K

P

U

B

L

I

S

H

E

R

S

Copyright © 2015 Lois Peterson

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording

or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without

permission in writing from the publisher.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Peterson, Lois J., 1952–, author

Three good things / Lois J. Peterson.

(Orca currents)

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN

978-1-4598-0985-7 (pbk.).—

ISBN

978-1-4598-0987-1 (pdf).—

ISBN

978-1-4598-0988-8 (epub)

I. Title. II. Series: Orca currents

PS

8631.

E

832

T

47 2015 j

C

813'.6

C

2015-901728-9

C

2015-901729-7

First published in the United States, 2015

Library of Congress Control Number:

2015935530

Summary:

Fifteen-year-old Leni copes with a mother who suffers from mental illness.

Orca Book Publishers gratefully acknowledges the support for its publishing programs

provided by the following agencies: the Government of Canada through the Canada Book

Fund and the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Province of British Columbia through

the BC Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

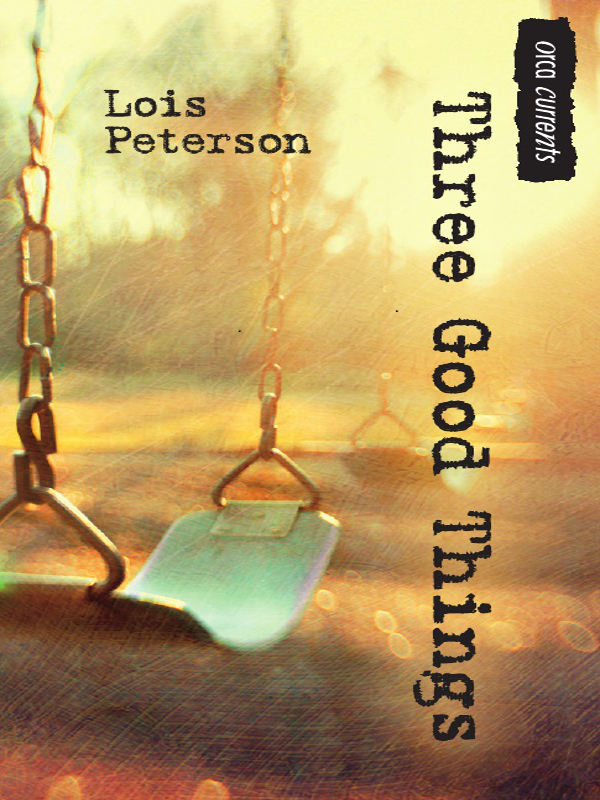

Cover photography by Getty Images

Author photo by E. Henry

ORCA BOOK PUBLISHERS

18

17

16

15

•

4

3

2

1

For my Sunday writing group,

Tony, Danika, Chris and Esther, who were

there at the beginning of the story.

o

n

t

e

n

t

s

h

a

p

t

e

r

O

n

e

“Get up, Leni.”

“Go away.” I groan and roll over.

“Leni.” Mom tugs on my covers.

I yank them away. “Not now. Not again.”

It’s dark under here, so dark that for a moment I don’t have a clue where I am. I

could be anywhere or nowhere, something or nothing.

My mother crashes around the room, muttering under her breath. I hold mine. Maybe

she will forget about me, forget about whatever is on her mind, whatever has her

going at whatever time this is.

Mom drags my quilt off me. “Come on. We’ve got to get out of here.”

This scenario plays out so often I should be used to it by now. It doesn’t matter

if we’re leaving something behind or headed somewhere specific. It’s all in my mother’s

head.

“It’s the middle of the night,” I say, as if it makes a difference to her. “I’m tired.”

She holds out my sweater. My shoes. “Get going.”

I haul the covers back over my head.

I hear my runners thud as they hit the floor. “Fine then,” she says. “I’ll go without

you.”

I lie still. I feel Mom next to my bed. Hear her breath. “Go on then, why don’t you,”

I mutter.

She doesn’t move.

I feel my blood pulsing in my ears.

“Okay. I’m going,” she says. But she still doesn’t move.

How many times have we been through this stupid song and dance? Testing each other?

She wants to leave. I want to stay. Even if this place is no better than any of the

others.

“Fine.” She walks away. A drawer opens and closes. A chair squeals. A zipper hisses.

I can see it all, the way she pulls together the few things that have been spread

around the place since we got here—one day ago, or three—into her old blue duffel

bag. Shoves her bulging purse under her arm, drags her red quilt from the couch or

cot she’s been sleeping on this time.

Now she’s standing at the door, looking back. Checking for whatever she may have

left behind.

As I wait her out, my breath moves up my chest into my throat.

When I can take the silence no longer, I peer over the top of my quilt. Mom is staring

at me. Not challenging or demanding. Pleading. “Leni. Come on. Please.” Her hair

is unbrushed. One side of her collar sticks up against her neck.

“Jeez!” I swing my legs over the side of the bed.

The one thing in the world worse than being dragged around by a crazy mom? If she

left without me.

“What is it this time?” I pull on my clothes, shove my stuff into my backpack and

grab my pillow and comforter, the box of cereal and two apples.

“Get moving,” she says. “I’ll tell you in the car.”

h

a

p

t

e

r

T

w

o

“The lottery?” I stretch out on the backseat. “You drag me out of bed in the middle

of the night because you won the lottery?”

“Not me. We. What’s mine is yours,” she says as she turns the car onto the street.

“Of course it is.” I punch my pillow and jam it under my head.

“Once word gets out, we’ll get no peace.” The car swerves as she turns to glare at

me. “You better not tell anyone.”

“Look where you’re going!”

Any other person might want to know how much we had won. When we’d get the money.

What she planned to spend it on.

I’d get more sense out of her if I asked her the meaning of life.

I have asked more than once why we can’t just live with my grandfather. All together.

Like normal people. “If you have to ask, you’re dumber than I think you are.” Mom

doesn’t mean to be cruel. It’s just that she can’t always censor what comes out of

her mouth.

Who knows what your grandfather’s secondhand smoke will do to my hair

and skin

, she said the last time I brought it up.

And when I asked Grand, he would sigh and say,

Oh, pet. It wouldn’t work. It just

wouldn’t.”

His house is small and dark, with fake wood panels on the walls. The furniture and

carpet are all some combination of mustard yellow and olive green, steeped in cigarette

smoke. We’ve never lived there. But it’s the only place I think of as home.

I drag my comforter over me and turn my face into the back of the seat. It will be

another long night of driving through the dark.

I don’t know how much later it is when I’m woken by the car stopping. “Where are

we?” It’s barely light out.

“I’m going for coffee.” Mom gets out and slams the door.

I clear the foggy window with my sleeve. We’re parked tight against a chain-link

fence. I loosen my tangled clothes and wipe my face with my collar. My mouth tastes

like a cat died in it.

I pull out my phone.

Grand answers on the fourth ring. “That you, Leni?”

“She’s done it again,” I tell him.

“Which is it this time?” He sounds tired. “Got into a fight over nothing? Or left

town?”

“She’s taken off. We’ve taken off.”

“Where are you?” I can hear the rattle of his coffeepot. I imagine him shuffling

around in his plaid housecoat, his veined feet shoved into old leather slippers.

“In an alley.”

“But where?”

“I have no idea, Grand. We drove. I fell asleep. I just woke up.”

“Let me talk to her.”

“She’s gone for coffee.”

“Ah.” I hear the longing in his voice. His coffee must have perked by now, burping

bubbles into the glass lid of his old pot.

“You go have your breakfast. I’ll get back to you when I know where we are.” “Good

girl. Before you go…what set her off this time?”

“She’s won the lottery.”

His bark could be laughter or disgust. “Seen the ticket, have you?”

“I haven’t, no.”

“Call me when you find it.”

“Then what?”

He sighs. “I don’t know, pet. I really don’t. But call me. I worry. You know I do.”

He hangs up.

That’s been his line for as long as I can remember.

I worry. You know I do.

This time I want to say,

So why don’t you do something about it? Why is it me who

has to go along with my mother’s crazy comings and goings? Put up with her highs

and lows? Make sure she eats? Takes her meds?

I imagine him at the kitchen table, slurping coffee, scrubbing at his

unshaven cheeks,

pulling yesterday’s paper toward him.

And hear his voice saying,

It wouldn’t work. It just wouldn’t

. He does what he can,

I guess. Always wants to know where we are, if things are okay. Tops up the bank

account when it’s getting low. Pays for my pay-as-you-go cell phone.

He pays and we go. That is how it works.

Mom comes back with coffee as I’m shaking out my comforter. “Take one.” She holds

out the cardboard tray. “I got you two honeys.” She thrusts out her hip so I can

grab the little packets from her pocket. She read somewhere that honey is better

than sugar.

“There’s nothing to stir it with.”

“Use your imagination.”

“Initiative, I think you mean.” She can’t see the look I give her.

The car is too close to the fence for me to open the front passenger door,

so I climb

into the back again. I root through the mess on the floor for something to stir

my coffee with. All I come up with is a red-and-white-striped straw. “Where’s the

ticket, Mom?” I ask.

“What ticket?”

“The lottery ticket that is going to make us the envy of all. And the target of every

salesperson on the planet.”

“Somewhere safe.”

Her purse is leaning against the passenger door. “In here?” I reach for it.

“You know a lady’s purse is private.” As she yanks it away from me, it flies back

and hits her shoulder. “Now you’ve made me spill my coffee!” She dabs at her pants

with a tissue.

“Where are we?” I ask.

“Richmond somewhere.”

“Richmond? It took all night to get just this far?”

“I made a few detours to throw everyone off the scent. Stopped when the gas light

came on.”

“What time is it?”

“Time you figured out not to nag me before I’ve had breakfast.”

I pull my comforter around my shoulders and close my eyes. “Wake me when you’re done.

I need a bathroom.”

Mom can sleep anywhere. Everywhere. But I can’t. The car gets colder and colder,

and the windows get more and more fogged up. Next time I look, she is asleep with

her mouth open, her empty coffee cup lying in her lap. Her purse bulges open beside

her. I ease it toward me an inch at a time. When I have it in my lap, I tent my comforter

over me to muffle any noise I might make.

I read somewhere that you can tell a lot about a woman’s life by what’s in her purse.

Mom’s is stuffed with her med bottles, a dozen empty vitamin bottles and a handful

of full ones. She’s collected a bunch of tiny fast-food salt and pepper packages.

Flyers about high-interest accounts. Credit-card applications. A reminder note for

a doctor’s appointment I doubt she kept. A stuffed green elephant she found under

a park bench. A single sock I’ve never seen before.

In her wallet is a five-dollar bill, more salt and pepper packages, a photo of me

perched on my dad’s shoulders when I was about four, eighty-five cents in change

and a little sachet of parsley seeds. Ah yes. Let’s plant a garden!

But, of course, no lottery ticket.

No doubt another of her many delusions.

h

a

p

t

e

r

T

h

r

e

e

I slide the purse back where I found it, drape the comforter over Mom and get out

of the car.

This alley is no different than any other. A stack of lumber leans against two recycling

cans with beat-up lids. A dead plant falling out of a wire basket lies next to a

patch of oil.

I zip up my jacket and start walking.

On the next block is a big park. It has a kiddie area with three swings, a jungle

gym and a slide. And a bench dedicated “To June and Matthew Long, who loved this

place.”

Parks are Mom’s favorite hangout too, wherever we are. It may be a throwback to

when she was little. Or when I was. I once told her she should write a book about

urban parks.

Do I look like Danielle Steel?

was all she said.

Although the swing is pretty small, I wedge myself in. “Push me,” I say aloud. “As

high as the sky.” Then I look around to make sure no one heard me. Everyone knows

only crazy people talk to themselves.

The park is part of a community center. There’s a library and an arts center and

a recreation center with an arena. In the parking lot, dads are hauling kids and

huge hockey bags out of cars.

I pump so hard, I am soon high enough to catch glimpses of a long highway with a

gas station on almost every block. Behind a mini mall where Mom probably got the

coffee stretch tidy blocks of houses surrounded by brick walls and high shrubs.

What it would be like to pump so high the swing cleared the top bar? Scary. Exhilarating.

Dangerous.

Talking to yourself and risk-taking activities are two signs of mental illness. I

read all about them once in a pamphlet in the waiting room of a doctor’s office while

Mom ranted at the doctor in an examination room.

Will knowing what symptoms to look out for keep me sane? Or send me around the bend?

I jump off the swing at its highest point, barely keeping my balance when I hit the

ground.

A woman is unlocking the library when I get there. She steps aside for me to enter.

“There’s always an early bird or two,” she says.

Another librarian sits staring at her screen. “Can I help you?” she asks without

looking up.

“I’d like to use the computer,” I say.

“We have two in the back corner.” She smiles up at me now. “First come, first served.

You’ll need a library card.”

“I’m just visiting.” I know how this works. “Can I get a pass?”

She hands me a slip of paper. “Log in with this number.”

Grand’s father bought him a set of

World Book

encyclopedia when Grand was eight.

He says it took him more than five years to study every entry from

A

to

Z

. That it

taught him everything he knows. How a cow’s stomach works. The weight of the Eiffel

Tower.

Who hit the most runs in the 1926 baseball season. All very useful.

But when I tried to explain Wikipedia to him, he shook me off. “Too high-tech for

this old geezer.”

I’ll probably be stuck on the

A

s forever. Today I’m reading about anthrax when someone

sits down at the station next to me.

First I take no notice. When I do glance over, I nearly fall off my chair. “What

the heck is that?” Beady eyes stare at me from the opening of a boy’s jacket.

“Never seen a ferret before?” He pulls the creature out like it’s a scarf. The ferret

dangles from his hands, blinking at me.

“Not this close.”

“Want to pet him?” He holds the thing out to me. “He’s quite friendly.”

“You gotta be kidding.” I pull away. “It’s a rodent!”

“Ferrets are not rodents.”

“Sure they are.”

He points at my screen. “Look it up if you don’t believe me.”

I only need to read a few lines. “Okay. So it’s not a rodent. You still shouldn’t

be dragging it around in your coat. It’s a wild creature. It needs to be free.”

“Bandit would get eaten alive in the big wide world.”

“Bandit?” It’s got a cute little face with black markings around its eyes.

“My sister Steph wanted me to change it to Fluffy.” He grins and tips back his head

as Bandit burrows under his chin. He’s skinny, with sandy hair and sandy skin and

the palest eyes I’ve ever seen.

“So do you keep it in a little cage with a little wheel to run on and a little bottle

to drink out of?” I don’t know why I’m having this discussion with this boy.

“Bandit has a cage with a long run. Ferrets need space,” he tells me. “But I

daren’t

let him loose too often. Or everyone would be walking around barefoot.” He holds

out his leg to show me the chewed-up sole of his runner. “He’s got a shoe fetish.”

I tuck my feet under my chair. These are my only shoes. “I never had a pet,” I tell

him. “But if I did, it wouldn’t be that.”

“I’ve got others. But Bandit is my favorite. ”

“Don’t tell me you’ve got mice in your pockets, hamsters up your sleeves?”

“Not here. At home. I have thirty-one in my menagerie. All kinds.”

“Thirty-one? Don’t you need a license or something?”

“Nah. I keep them in the garage. For my twelfth birthday, Dad cleared it out and

helped me make cages. Now he keeps his car in the driveway.”

The last thing I got from my father was a ten-dollar movie card in the mail.

That

isn’t even enough for popcorn with the movie.

“Want to come over and see?” the boy asks. “I’ve got a pair of albino rabbits. All

girls love rabbits.”

How many girls? I wonder.

I’m not much of an animal lover. I’ve seen rats in alleys. A dead cat under a bed.

Too many mean dogs.

“Well?” the boy asks.

Before I can answer, a man appears at my side. “You using that? Or can I get on?”

I look at the boy, then back at my screen. “Yes, I am using it.”

“What about you?” the man asks Bandit’s owner.

“It’s all yours.” When he gets up, he keeps one hand on his stomach. A bump there

shows where the ferret has settled. Either that or this kid’s got a huge tumor.

“I’m Jake, by the way.” He puts out his spare hand.

What kid our age shakes hands? And who knows what kind of deadly animal germs he’s

carrying around on his skin?

“I’ve got to get back to work.” Better be prepared for when the next anthrax scare

happens.

“Maybe I’ll see you around.” He blushes. “And your name is?”

“It’s Leni.” I keep my hands on the keyboard.

“See you around, Leni.”

I don’t watch him walk away. But I hear every step, then the door opening and closing

behind him.

It turns out that ferrets are in the

Mustelidae

family

.

Also known as the weasel

family. Even rodents or weasels have to be easier to understand than people, I figure.

The man at the next computer is on a dating site. I imagine how he might describe

himself.

Overweight, middle-aged man with body odor wishes to meet

soul mate

. Good

luck with that, I think. Then I catch myself and cringe. He’s probably another lonely

schmuck.

I check Craigslist for rental listings before I log off and then grab a copy of

Country

Living

from the magazine rack. I turn to the ads for stainless-steel plumbing and

Irish linen towels. Wrought-iron hardware and blown-glass lamps. After Dad left and

Mom started moving us from place to place, I filled a scrapbook with details of the

house I want one day. I picked paint colors, drapes, throw rugs and end tables.

The scrapbook got left behind in some dump we stayed in.

Whenever I open one of these home-decorating magazines, I feel a worm of envy in

my gut.

For everyone else’s life.