Threshold Resistance (17 page)

Read Threshold Resistance Online

Authors: A. Alfred Taubman

With my sons Robert and William.

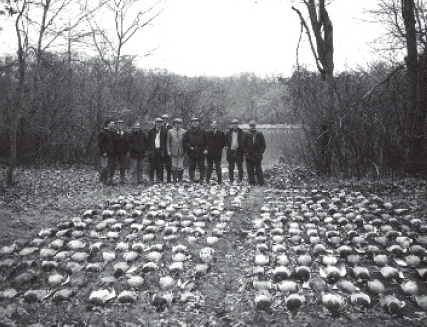

Doing my part to thin out the duck population on Long Island.

Karl Lagerfeld took this photograph of my wife Judy and me in 1998. It's one of our favorites.

But underneath my anger I realized this was not just about me. This unthinkable scandal was threatening to bankrupt a 250-year-old company. Starting in January 2000, customers filed civil suits, alleging they had been cheated by the collusion. Investors were fleeing from our stock like rats abandoning a sinking ship. Through no fault of their own, and as the stock fell, Sotheby's employees saw their life savings evaporate. My continued presence on the board was making things worse for everybody.

But stepping down didn't mean giving up. According to

Forbes

and

Fortune,

I was worth hundreds of millions of dollars. But my most precious asset was my good nameâthe one thing my father had taught me to protect at all costs. I remembered the lengths he went to during the depression to make good on his debts and preserve his reputation.

This was a huge blow, and it was certainly not how I had planned on spending my seventy-sixth year on earth. It was a confusing and difficult time. I was angry and frustrated at Dede Brooks and at the prosecutors, and fearful of what the future might bring me. Developers generally don't look back; we look to the future. It's not that we don't have memories or learn from the past. Rather, when you're involved in a construction project or a leasing campaign, you have to continually move forward, or else you lose time, momentum, and money. Problems have to be faced head-on in a realistic way. That's how I approached my legal difficulties. I had to fight back. And so as I always had done, I set out to find the best professionals I could find.

On the recommendation of Don Pillsbury, we retained the law firm of Davis Polk & Wardwell. Robert Fiske, a former U.S. Attorney and the first Whitewater independent counsel; Scott Muller, a highly respected litigator (Scott served as general counsel to the Central Intelligence Agency for several years after my trial); and Jim Rouhandeh headed the Davis Polk team. They were all exceedingly

smart, intensely focused, and seasoned in the complicated world of antitrust prosecution.

This was to be a very messy two-front war. Civil challenges were mounting as a sitting grand jury was determining potential criminal charges. Davis Polk was prepared to lead my defense on both the civil and criminal battlefields. The continuity was very important.

Recognizing that the fight of my life would also be played out in the court of public opinion, Christopher Tennyson, my longtime communications adviser, brought veteran crisis public relations guru John Scanlon on board. With his white beard, red hair, and piercing blue eyes, John looked more like an Irish poet than a tough-as-nails PR guy. But he had earned a reputation for being a first-class advocate for his clients, and he was on a first-name basis with the most important electronic and print journalists in New York. At the first meeting with John in my New York office, at 712 Fifth Avenue, he brought us what he described as very bad news.

“Dede has hired Steven Kaufman, the flipper, and that's not good,” said Scanlon.

“What's a flipper?” asked Tennyson.

“An attorney specializing in offering up a superior to make a deal with the prosecutor,” Scanlon explained. “Kaufman rarely goes to trial. He has only one play in his playbook, but he runs it very well.”

If Dede's strategy hadn't been clear before, it was now. And this time the superior being offered up in exchange for leniency was me.

In one of the many strange and tragic twists in this saga, John Scanlon suffered a fatal heart attack in his Manhattan apartment on May 4, 2001, the morning I was arraigned in U.S. District Court on a single charge of price-fixing. Heading into the eye of the storm, we lost a terrific guy and an important member of our team. Two of John's partners, Lou Colasuonno and Laura Murray, stepped in admirably to assist us.

The civil side of the dispute was relatively cut-and-dried. Dede and Davidge, who had been the CEOs of their respective companies, had admitted their collusion. Both companies, therefore, were guilty as charged. David Boies, the high-profile attorney, represented the “class” of auction house customers that brought suit against Sotheby's and Christie's. He hadn't fared too well in

Bush v. Gore,

but he sure did all right with us. He won a settlement of $256 million from each company for his clients.

Christie's owner, François Pinault, paid all $256 million of his company's portion, and I agreed to contribute $186 million of Sotheby's civil settlements personally. My level of participation was consistent with my majority ownership position. I also was fully aware that without my assistance, the company faced the very real prospect of bankruptcy. These were decisions made out of enlightened self-interest, not charity. Sotheby's represented one of my most significant investments. Abandoning the company and fending for myself would have destroyed a personal asset that, even in the midst of scandal, was worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Besides, all this had happened on my watch. I was committed to the survival of this extraordinary franchise and the preservation of its employees' livelihoods.

David Boies is an interesting guy. I've never met him, but I recently read his book,

Courting Justice.

Chapter 9, “The Auction House Scandal,” presents his insightful account of the civil settlement. Boies and I, it turns out, have a lot in common. He, too, suffers from dyslexia. He's a skilled poker player; I do pretty well at bridge. He grew up in Orange County, California, home to the Irvine Ranch. More important, there is probably no one on the planet who studied the evidence in this case with more skill and intensity than Boies. And what was his conclusion? Here's what he told author Christopher Mason in an interview for Mason's meticulously researched book,

The Art of the Steal:

“There wasn't any real evidence that they fixed prices,” Boies noted, referring to Taubman and Tennant, “just that they had a lot of meetings.” It was a stunning observation coming from the lawyer who had spent the spring and summer of 2000 poring over documents and taking depositions in an attempt to establish Taubman's guilt.

In other words, after examining all the evidence, Boies concluded that while the two companies' CEOs, Dede Brooks and Christopher Davidge, willingly admitted that they met and agreed to fix prices, there was no evidence that the two companies' chairmen were involved in any way.

One thing David Boies and I do not have in common, however, is our taste in restaurants. In

Courting Justice,

Mr. Boies reveals that when his law firm wrapped up the auction house suits and secured a $26 million fee for four months' work, he celebrated by taking his wife to dinner at Sparks Steak House in Manhattan. I've got nothing against Sparks (John Gotti put the place on the map). But that kind of payday merits a night out at Daniel or, if you want a great steak, Peter Luger in Brooklyn.

Thanks in large measure to David Boies's legal and negotiating acumen, the civil challenges were resolved swiftly (and expensively). But the potential exposure on the criminal side was far more frightening. Over the years, I had dealt with civil litigation many times. It's a hazard and natural byproduct of doing business. There were times I won, and times I lost, and times when settling made economic and business sense. I wasn't happy about paying to settle the civil suits, but I could survive and live with it. This was different. Much different. Criminal prosecution brought with it the prospect of jail time. Was the Justice Department going to pursue criminal charges against me? It was uncertain for all of 2000 and the first quarter of 2001. What was certain, however, was that prosecutors were hard at work making it difficult, if not impossible, for me to defend myself.

From the outset, the deck was stacked against us. In an action that startled even the most seasoned judicial observers, the U.S. Justice Department granted Christie's, a foreign-owned company, and all its employees, including Christopher Davidge, amnesty from prosecution in return for their cooperation in the effort to essentially cripple or destroy Sotheby's and put me in prison.

Now, I understand that the amnesty program has yielded important victories for our country's prosecutors. It's easy to applaud the decision to isolate a mob boss or terrorist by protecting informants from criminal prosecution. But the practice seriously distorts the concept of equal justice. Here's how the writer James B. Stewart, in the October 15, 2001, issue of the

New Yorker,

described the questionable practice in my case:

Prior to 1993, a price-fixer who wanted amnesty for testifying against a co-conspiring competitor had to take his information to the Justice Department before an investigation was under way. But that year the department began offering amnesty even after an investigation was in progressâto whoever came in the door first and promised that all its employees would confess and cooperate against other conspirators. From a law-enforcement perspective, the program has been a success. Since it began, requests for amnesty, which under the old program had averaged one a year, jumped to more than one a month, and in the last four years the government has reaped fines of $1.7 billion. Many defense lawyers, mindful of the innate American distaste for informers, have argued that such incentives to cooperate are too generous, extravagantly rewarding testimony from people who are criminals and who tailor their testimony to what prosecutors want to hear. But so far none of the cases have generated a public outcry.

Unfortunately, neither would mine, even though Christie's received this “extravagant” treatment without meeting the most

fundamental requirements to qualify for the program. First of all, according to the Justice Department's guidelines, the instigator of the price-fixing is ineligible for amnesty. If you started it, forget it. Even to this day, nobody in the world (including the prosecutors, I believe) believes Sotheby's or I started this thing. Not a soul. In Christopher Mason's book, Christie's senior executive François Curiel stated what everybody has always understood to be the truth: “Chris [Davidge] is a chief manipulator with a capital Câ¦He did it very, very cleverly.” Granting amnesty to the party starting the wrongdoing could lead to all sorts of problems and injustice. But the Justice Department conveniently ignored this disqualification.

According to the rules, you can also forget about amnesty if you fail to come forward in a timely manner with your information. Christie's didn't even come close. The collusion between Dede and Davidge was an open secret at Christie's at the highest levels of the company in London and New York. In 1997, three years

before

Christie's knocked on the door of the Justice Department, Lord Hindlipâthe man who succeeded Anthony Tennant as Christie's chairman and who has admitted publicly to knowing in 1995 about the two CEOs getting together to discuss the seller's commissionsâprovided Davidge with the following handwritten note:

Dear Christopher:

I am writing to assure you that, in the unlikely event that it should happen you are forced to resign your position because of the antitrust hearings in the U.S., Christie's will fully protect your position as per your contractâ¦

Testimony in court would reveal that even Christie's new owners were well aware of Davidge's misdeeds long before they decided to “do the right thing.” In fact, when confronted with a confession by Davidge, François Pinaut's people didn't head straight to the authorities.

They sweetened Davidge's severance payments in return for his promise of silence! The Justice Department conveniently ignored this disqualification as well.

The power to grant amnesty from prosecution in a criminal trial is an awesome responsibility. Misused, it has the potential to destroy our system of justice. That's why Congress granted that power with carefully crafted rules and guidelines. The antitrust division of the U.S. Justice Department allowed Christie's to avoid prosecution, even though the company didn't even come close to qualifying for the amnesty program.

We are a nation of laws, not men. That bedrock principle was driven home to me many years ago when I had the honor to attend the dedication ceremonies for the Damon J. Keith Law Collection of African American Legal History at Wayne State University in Detroit, an archive dedicated to the accomplishments of African American lawyers and judges. Judge Keith, who has served on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit since 1977, is a good friend of mine and one of the most respected jurists in the country. One of the nation's first African American federal judges, Damon has written many landmark decisions and trained many distinguished law clerks. Michigan's current governor, Jennifer Granholm, started her legal career clerking for Judge Keith, as did Lani Guinier. Guinier, who is best known for having been nominated by President Bill Clinton to be assistant attorney general for civil rights, was the keynote speaker that evening. She told a story I will never forget.

In the early 1970s, a gang of hateful racists, known as the White Panthers, bombed the offices of the Central Intelligence Agency in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The police arrested the bombers, but only after relying on what turned out to be unauthorized wiretaps. Guinier was clerking for Judge Keith when the White Panthers' appeal came before him. As disgusted as he was with the perpetrators and their violent act, Judge Keith overturned the conviction, rebuking law enforcement

officials who argued that national security gave them the right to ignore established procedures designed to protect the rights of all citizens. Though challenged by President Nixon and Attorney General John Mitchell, Judge Keith's ruling was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court. Guinier explained that the young law clerks, many of them African Americans, were at first upset when Judge Keith arrived at his difficult decision. But as he explained to them the overriding importance of the Constitution and the rule of law, they learned a very important lessonâa lesson they carried with them into their distinguished legal careers. For that higher wisdom, they loved and respected Damon even more than they had before.