Thrush Green (24 page)

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Country life, #Pastoral Fiction, #Thrush Green (Imaginary Place), #England, #Fiction

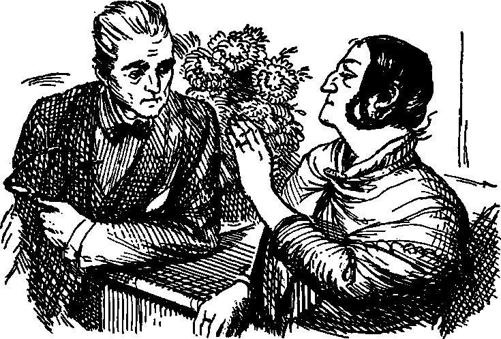

"Don't think I'm unhappy about it," said the doctor truthfully. "I'm glad. The work goes on, that's the comfort. I only wish I'd realized that years ago and saved myself a mint of heart searching."

He turned to the old lady.

"And that's what I want you to face, as I did. You must have help. Let someone share the load and you'll be of some use. Be too proud to ask for it and you'll go down under it. We're both in the same boat, my old friend."

Mrs. Curdle nodded thoughtfully. The doctor, seeing her engrossed in thought imagined that she was trying to choose, from among her tribe, one best suited to her purpose.

"If Ben doesn't seem the man for it—" he began. But the old lady cut him short.

Eyes flashing, and back as straight as a ramrod, Mrs. Curdle answered indignantly:

"Who said Ben wasn't the man for it? There's nothing wrong with my Ben now. You never let me finish the tale!"

Humbly and hastily Dr. Bailey begged Mrs. Curdle's pardon, secretly delighted at this flash of her old spirit.

And within five minutes he had heard of Ben's transfiguration, of his proposed marriage with young Molly Piggott and, best of all, of Mrs. Curdle's decision to take him into partnership that very day on her return to the caravan.

"We shan't forget this May the first, either of us, Mrs. Curdle," said the doctor, when he had heard her out. "You'll see. My practice will go on, and your fair will go on."

"They'll both go on!" agreed Mrs. Curdle, with great satisfaction.

The two old friends looked at each other and smiled their congratulations.

"And now," said Dr. Bailey briskly, "I'm going to have a look at you."

Later, Mrs. Curdle, with a light heart, crossed the road again. She had made her parting from the Baileys in the hall, but now with her feet on the grass of Thrush Green she turned to look once more at the house where she had received such comfort of body and mind.

Silhouetted against the light of the open doorway stood the doctor and his wife, their hands still upraised in farewell. Mrs. Curdle waved in return and turned toward her home.

In her cardigan pocket lay some pills and a simple diet sheet, but it was not of these that Mrs. Curdle thought. She was thinking of Dr. Bailey, whose good advice had never failed her throughout her long life. Her way now was clear.

With a tread as light as a young girl's, Mrs. Curdle, her fears behind her, hurried to find Ben.

He should hear, without any more waste of time, of his good fortune and the future of the fair.

Meanwhile, the doctor and his wife had returned to the sitting room. Mrs. Bailey had carried in a tray with soup, fruit and a milky drink, for, with their visitors, supper had been delayed and the hands of the silver clock on the mantelpiece stood at a quarter to ten.

They supped in silence for a while. Then Mrs. Bailey, putting her bowl down, said:

"And does the fair go on?"

"Yes," said the doctor. "I'm thankful to say it does."

The music surged suddenly against the window with renewed vigor, and they smiled at each other.

As Mrs. Bailey stacked the tray she noticed that the doctor's eyes strayed many times to the gaudy bouquet which flamed and flared like some gay bonfire.

"I'll take those flowers to the larder shelf," said Mrs. Bailey, advancing upon them.

"No," said her husband, and something in his voice made her turn and look at him. He sat very still and his face was grave. "I'd like them left out."

Mrs. Bailey could say nothing.

"We shan't see the old lady again," said Dr. Bailey. "I doubt if she has three months to live."

18. The Day Ends

A

T HALF PAST TEN

the lights of Mrs. Curdle's fair went out and the music died away. The last few customers straggled homeward, tired and content with their excitement, and by the time St. Andrew's clock struck eleven Thrush Green had resumed its usual quietness.

A few lights, mainly upstairs ones, still shone from some of the houses around the green, but most of the inhabitants had already retired, and dark windows and empty milk bottles standing on the doorsteps showed that their owners were unconscious of the happenings around them.

The church, "The Two Pheasants," and the village school were three dark masses, but a small light twinkled between the latter two. It shone from Molly Piggott's bedroom where the girl was undressing.

The blue cornflower brooch lay on the mantelshelf and beside it a small ring.

"You shall have a proper one, some day," Ben had promised, "not just a cheap ol' bit of trash from the fair." But to Molly it was already precious—a souvenir of the most wonderful day in her life.

She had parted from Ben only a few minutes before, when he had told her of his new status in the business, and she had promised to be up early in the morning to see him again before the caravans set off on their journey northward.

She clambered into the little bed, which lay under the steep angle of the sloping roof, keeping her head low for fear of knocking it on the beam above.

Carefully she set her battered alarm clock to five o'clock, wound it up and put it on the chair close beside her. Then, punching a hollow in her pillow, she thrust her dizzy dark head into it and was asleep in two minutes.

In the next bedroom Mr. Piggott, asleep in his unlovely underclothes, as was his custom, stirred at the thumpings made by his daughter's bed and became muzzily aware of her presence in the house.

Vague memories of a young man, a bottle of whisky and Molly's future swam through his mind. No one to cook for him, eh? No one to clear up the house?

"Daughters!" thought Mr. Piggott in disgust. "Great gallivanting lumps, with no idea of doing their duty by their poor old parents!"

He relapsed into befuddled slumber.

Ruth Bassett's light still shone above the bed. She sat propped against the pillows, a book before her, but her attention was elsewhere.

Dr. Lovell had left an hour or so before and the memory of their pleasant time together warmed her unaccountably. She had scrambled eggs in the kitchen while he had supervised the toast, and together they had sat at the kitchen table enjoying the result, brewing coffee and talking incessantly.

She had never felt so at ease in anyone's company, and the thought that he had sought her out to tell her his wonderful news touched her deeply. Plainly, he was as devoted to Thrush Green as she was. And who can blame him? thought Ruth, as a distant cry from one of the Curdle tribe reached her ears.

It had cured her of her misery and given her new hope. It had, as it had always done, provided her with comfort and contentment. Her decision to make her home there filled her with exhilaration. Tomorrow, when Joan and her husband returned, they would make rosy plans.

For a moment her mind flitted back to the cause of this decision. The figure of Stephen, tall and fair-haired, flickered in her mind's eye, but, try as she would, she could not recall his face. It seemed a shocking thing that one who had meant so much could so swiftly become insubstantial. The ghost of Stephen had vanished as completely as the man himself and, Ruth observed with wonder, her only feeling was of relief.

She put her book to one side, switched off the light and settled to sleep, secure in the knowledge that the dawn would bring no torturing memories, but only the wholesome shining face of Thrush Green with all it had to offer.

Young Dr. Lovell was writing a letter to his father, telling him of Dr. Bailey's offer, asking his advice about the financial side, and explaining the future possibilities of the practice.

He wrote swiftly in his neat precise handwriting and covered two pages before he paused. Then he lit a cigarette and stared thoughtfully at his landlady's formidable ornaments on the mantelpiece.

It is not in the nature of young men to open their hearts to their fathers and to tell them of their private hopes and feelings, particularly when a young woman is involved, and Dr. Lovell was no exception. But he was fond of his father—his mother had been dead for ten years—and he wanted him to know that this offer meant more to him than just a livelihood.

His thoughts turned again to Ruth. He knew now, without any doubt, that she would always be the dearest person in the world to him. As soon as she had recovered sufficiently from her tragedy to face decisions again he would ask her to marry him.

Life at Thrush Green with Ruth! thought young Dr. Lovell, his spirits surging. What could anyone want better than that?

Smiling he picked up his pen and added the last line to his letter:

"I know I shall always be very happy here."

He sealed it, propped it on the mantelpiece against a china boot, and went whistling to bed.

In her cottage nearby lay Miss Fogerty from the village school. She was fast asleep. Her small pink mouth was slightly ajar, and her pointed nose twitched gently over the edge of the counterpane, for all the world like some small exhausted mouse.

It had been a tiring day. The children were always so excited on fair-day, and Friday afternoon meant that she had to battle with her register amidst the confusion of twenty or so young children playing noisily with toys brought from home—a special Friday-afternoon treat.

Her last thought had been a happy one. Tomorrow it was Saturday. If it were lovely and sunny as today had been her weekly wash day would be most successful, she told herself.

Her Clark's sandals were prudently put out underneath the chair which supported her neat pile of small clothes. Miss Fogerty was a methodical woman.

"No need to set the alarm," she had said happily to herself as she folded back the eider-down. "Saturday tomorrow!"

And with that joyous thought she had fallen instantly asleep.

Ella Bembridge and Dimity Dean had taken the advice of Dr. Bailey and settled to sleep early.

Dimity had fallen into a restless slumber disturbed by confused dreams. She seemed to be standing knee-deep in a warm crimson pond, stirring an enormous saucepan full of parsley sauce, while Mrs. Curdle and Ella stood by her, wagging admonitory fingers, and saying, in a horrible sing-song chant: "Never touch the stuff—it's poison! Never touch the stuff—it's poison!"

Ella found sleeping impossible. Her legs hurt, her rash itched, and the shooting pains in her stomach, though somewhat eased by Dr. Lovell's white pills, still caused her discomfort.

Morosely, she catalogued the day's tribulations, as others, less gloomily disposed, might count their blessings.

"Visit to the doctor—a fine start to a day. Blasted parsley sauce. Rubber gloves. That boiling dam' dye. Dotty's Collywobbles. Two more visits from doctors, to top the lot—and Mrs. Curdle's hurdy-gurdy for background music! What a day!"

She glowered malevolently at Mrs. Bailey's daffodils, a pale luminous patch in the darkness. One ray of hope lit her gloom.

"At least May the second shouldn't be quite as bad as May the first has been!"

Somewhat comforted, Ella moved her bulk gingerly in the bed, for fear of capsizing the leg guard, and waited grimly for what the morrow might bring forth.

Away in the fields below Lulling Woods the creator of poor Ella's latest malady lay in her bed.

Dotty Harmer's room was in darkness, lit only by the faint light of the starlit May sky beyond the grubby latticed panes.

Dimly discernible by Dotty's bed was a basket containing the mother cat and one black kitten. Much travail during the golden afternoon had only brought forth one pathetic little stillborn tabby, sadly misshapen, and ten minutes later this fine large sister kitten. Dotty had buried the poor dead morsel in the warm earth, shaking her grizzled head and letting a tear or two roll unashamedly down her weather-beaten cheeks.

The survivor was going to be a rare beauty. Dotty could hear the comfortable sound of a rasping tongue caressing the baby between maternal purrs, and cudgeled her brains for a suitable name.

Blackie, Jet, Night, Sooty—too ordinary! decided Dotty, tossing in her bed.

She thought of the glorious day that had just passed and remembered the spring scents of her garden as she had awaited the birth.

Should be something to do with May, pondered Dotty. May itself would have done if it had been a pale kitten, but somehow—a dark little thing like that.... She resumed her meditations and the memory of Molly and her dark young man came floating back to her.

Gypsy! thought Dotty, groping toward the perfect name. She felt herself getting nearer. Something that was dark, magnificent and connected with May the first, she told herself. It came in a flash of inspiration.

"Mrs. Curdle!" cried Dotty in triumph.

And with the rare sigh of a satisfied artist, she fell asleep.

Gradually the lights dimmed in the old stone houses around Thrush Green, but still one shone in Dr. Bailey's house.

The good doctor himself was asleep. He had had the busiest day of his convalescence and had retired more exhausted than he would admit to his wife.

The last sad interview with Mrs. Curdle had been a great strain—greater because his grief had to be kept hidden behind his kindly professional mask in front of the old lady. Her case, he knew, was hopeless, and when her fair came to rest for the winter that year he had no doubt that she who had ruled its kingdom for so many years would be at rest too.