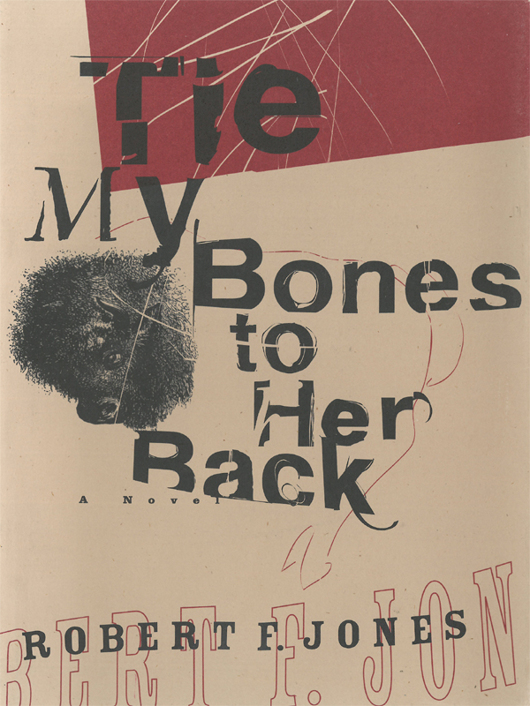

Tie My Bones to Her Back

Read Tie My Bones to Her Back Online

Authors: Robert F. Jones

Copyright © 1996, 2014 by Louise Jones

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or

[email protected]

.

Skyhorse® and Skyhorse Publishing® are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at

www.skyhorsepublishing.com

.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-62636-574-2

eISBN: 978-1-62873-940-4

Printed in the United States of America

FOR ANNIE PROULX

In our intercourse with the Indians it must always be borne in mind that we are the most powerful party . . . We are assuming, and I think with propriety, that our civilization ought to take the place of their barbarous habits. We therefore claim the right to control the soil they occupy, and we assume it is our duty to coerce them, if necessary, into the adoption and practice of our habits and customs . . . I would not seriously regret the total disappearance of the buffalo from our western prairies, in its effect upon the Indians, regarding it rather as a means of hastening their sense of dependence upon the products of the soil

—Columbus Delano

U.S. Secretary of the Interior (1873)

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the Ucross Foundation in northern Wyoming and its executive director, Elizabeth Guheen, for providing me with a residency during the month of April 1993, while I traveled and researched a small part of the Great Plains. Thanks also to Claire Kuehn, archivist-librarian of the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon, Texas, for granting me access to invaluable material on commercial buffalo hunting in western Texas during the 1870s. The custom gunmaker Steven Dodd Hughes of Livingston, Montana, an expert on nineteenth-century firearms who is familiar with most of the weapons mentioned in this book, read my manuscript for accuracy; I’m grateful for his time and effort. My editors at Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Margaret Ferguson and John Glusman, demonstrated great patience and a willingness—above and beyond the call of duty—to deal with obscure and violent subjects. To both of them my utmost gratitude and respect.

Introit

The virgin prairie: no wheel ruts, no chimneys, no spiders yet—the bison in his plenitude. No history here, no numbers, not even the resonance of place-names. No villains, no heroes. And if once the land had them, who knows what they signified?

Just the land, flat, empty, endless and timeless, cut to the bone by the rare run of water, pounded by the sun.

The wind blows steadily, night and day, driving men and animals wild.

Then it stops.

The heat builds.

Buffalo gnats swarm everywhere, fleas and lice, the stench of rotting meat. The seasons swing through impossible arcs, heat and cold, sunglare, starglare, frostbite, flood and snow, mirage. Black, dry tongues in skulls that still breathe; a herd of elk frozen in place, standing; mummified antelope withering within their sun-parched hides; frost-puckered men losing toes and limbs to the cold. A couple of newcomers frozen by the norther; other wayfarers come upon them, look down from their gaunt horses; the weather’s victims snowblind and helpless, begging for mercy, just a bullet or two, for pity’s sake; they ride on, but one goes back and shoots them—is it mercy? No, he merely wished to see if his rifle would still fire in such a frost as this. Scarce time for pity here.

When horses are starving, men will feed them meat and the horses will eat it as readily as hay. You’ll see them now and then, hobbled beyond the firelight, gnawing the bones of long-gone wayfarers, whether frozen to death or baked alive matters not to your pony.

The Indians believe there was a time when all animals, even buffalo, preyed upon men and devoured their flesh. But that was long ago.

The buffalo herd moving through time: big ugly shaggy smelly louse-ridden powerful animals, black-humped, black-horned, huge heads and tiny feet, bellowing, roaring, grunting, pursued by wolves, ridden down by Indians, gunned in their milling millions by hide men, shot and puking blood, hundreds of them pouring into rivers and over cliffs, breaking their bones and dying, or drowning and dying, or doomed to starve with broken backs and legs, and the rest running right over them, through them, with no compassion, no concern, driven mindlessly, as are we, by their nature, our nature.

These lives, our lives, are merciless—they will make you cry out for emptiness—cry out for a single redeeming message.

You’ll not get it here, unless . . .

The Human race is vile, unthinking Nature best, and Prayers won’t help us anyway.

The plains go on forever.

PART

I

1

T

HE

P

ANIC OF

1873, precipitated by the failure of Jay Cooke’s banking house in New York, spread rapidly from east to west. Armies of tramps and incendiaries moved through the land that fall, jobless, roofless, hopeless men, hamstringing blood horses in their anger, burning barns, grabbing broody hens and cooking them—barely plucked, still quivering—over smoky fires made of planks they tore from the floors of chicken coops, wolfing down the red-veined meat half raw. Smoke rose thin in bitter blue-gray columns through the autumn woods and the stench of house fires lay heavy on the land.

In any switchyard along the North West Railroad’s right-of-way through Wisconsin, wherever the cars were going slow enough, you could see the tramps drop from the freight cars like ticks from a dead dog’s belly, swollen in the wrappings of their filthy rags, shuffling off through the dead-fallen leaves with an ominous whisper, some with shiny new boots, cocksure for the minute.

A farmer residing near Clyman went out to his pigsty one morning and found two dozen saddleback porkers lying dead with their throats slit. He could see from the tracks in the jelled purple blood that the other eleven had been carried away.

In the silent woods near Rhinelander, the bodies of unidentified men are found dangling from tree limbs. A tramp falls from a freight car on the outskirts of Butler, the wheels nip the top from his skull. Tramps turned away from a farmhouse door not far from North Prairie go into the barn, cut the throats of three cows, leaving a card spiked on a bloody horn: “Remember this when next you refuse us.”

Suicide takes many forms. Paris green. Carbolic acid. The noose. The revolver. One man beats himself to death with a hammer. Another, demented, eats a dozen cigar butts and chokes to death when he vomits them back up. Yet another lashes sticks of dynamite around his torso, caps them, lights the fuse . . .

A troop of fifty hoboes invades the town of Bad Axe. They terrorize the citizenry and burn the county courthouse. Others occupy Peltier’s Store, break into the wine cellar, and devour the sausage and crackers and all but three of the dill pickles. An affray ensues, in the course of which one tramp shoots another over the division of spoils. More gunshots follow. When the smoke clears, the sheriff counts nine dead bodies. Another four hoboes seriously wounded, three not expected to live.

A plague killed many children that year—”the black diphtheria”—infants mainly, though older children, too: a lovely girl of seventeen in Kewaunee, whose picture ran in the paper; and every day the bells tolled another dozen funerals. In some families, two or three children died in a single day. A sore throat at first, a slight fever, then the bacillus raging out of control—throat tissue eaten away, replaced by a tough gray membrane, the telltale sign of imminent death. Suffocation swiftly ensues. (Or worse, prolonging suspense because it is slower, the infection leaches downward through the esophagus, finally inflaming the walls of the heart.)

The babies looked lovely in their embroidered burial gowns: their sightless glances half lidded, blue eyes and silky blond hair, a bit of rouge on their plump smooth cheeks, their bottoms scrubbed clean, held upright, in tiny pine coffins lovingly sawn and tacked together, on hooks implanted in their backs by the town photographer. Family mementos. Many mothers went crazy with grief. Women walked the streets of Wisconsin—the entire Northwest—with their eyes deranged and dead babies in their arms. They walked into stores the way they had when their babies were alive, then sat in chairs before the cast-iron stoves and rocked until the babies began to stink. No man dared approach them. Some women felt so guilty about the deaths of their infants that they cut their own throats with case knives or sheep shears, some threw themselves into cisterns, others laid their heads upon the railroad tracks and allowed the thundering wheels to shatter their skulls. One woman near Eau Claire was chopped into three pieces by the wheels.

Yet the

Badger Banner

reported: “More poetry is written in Wisconsin than in any other state in the Union.”

A

HARD FROST

that morning, the morning that changed her life, and Jenny Dousmann snug in her bed. It was cold in the loft, warm under the goosedown comforter. She said a little prayer.

Lieber Gott, mach’ mich fromm, dass ich in dein Himmel komm’

.

Amen.

Dear God, make me pious, so that I go to Heaven . . .

She waited until she heard her father rattling in the kitchen, firewood snapping in the stove, then threw back the cover, jumped out of bed, hiked her nightgown, squatted over the chamber pot, and dashed for her clothing. She was a strongly built girl with fair hair and fair skin, large green eyes, and freckles—faint ones—on her cheekbones. The coffee was done by the time she came down the ladder. Vati was out in the barn milking the cows. She punched the air from some bread dough left to rise the previous evening, shaped it into the pans, and set the dough to rise a second time. She covered the pans with damp towels. When she had finished, she went out to the henhouse to gather eggs. She heard her mother stirring in the big bedroom as she closed the kitchen door. Mutti would put the bread in the oven when it was ready. That was their daily routine.