To Hell on a Fast Horse (12 page)

Read To Hell on a Fast Horse Online

Authors: Mark Lee Gardner

Sumner became the Kid’s safe haven and base of operations. Charlie Bowdre found part-time employment as foreman of the Thomas Yerby ranch in an isolated area known as Las Cañaditas (Little Canyons), ten or so miles northeast of Sumner. Tom Folliard signed on with Yerby as well. Doc Scurlock followed the lead of the Coes and abandoned New Mexico for Texas, and never saw the Kid again. No matter, Billy never lacked for friends, and Fort Sumner offered plenty of girls, lots of dancing, some gambling and horse racing, and a whole lot of other people’s cattle and horses out on the open range that could be sold to more than a few unquestioning buyers. Even better, there was not a lawman in the Territory who was brave enough to go after the Kid and his confederates—not just yet.

PAT GARRETT KNEW THAT

some of the men at his wedding

baile

were wanted by the law—everyone did. Most men in New Mexico Territory had a past—and some of them were hardened killers. That, too, was not unusual for the time and place, nor was it any cause for alarm. It was a time for celebration, and the attention was on Garrett and his bride. But as the guests watched the newlyweds dance, Juanita suddenly collapsed in what was described as some kind of fit or attack. She was quickly carried to a bed in a nearby room, where she died the next day. No one knew what happened to her. Her final resting place remains undiscovered, and she left no photographs, and no children. All that survived was a scar on Pat Garrett’s psyche and a faint memory in the minds of a few Fort Sumner old-timers.

More than most, it seems, Garrett and the Kid had experienced the tragic loss of loved ones. There was a good deal that the two had in common, actually: certain leadership qualities, for one, and their well-known fondness for the

baile,

horse racing, and gambling. Both were men you would want on your side in a fight. Garrett and the Kid were not good friends at Fort Sumner—but they were not enemies either. They saw each other frequently enough, and they had a healthy respect for each other, certainly each other’s ability to take care of himself. Garrett was usually serious and the Kid was usually boisterous, and they each had a reputation as a better-than-average shot with a six-gun; they were considered the two best shooters at Fort Sumner. On a slow day, and there were more than a few of those there on the Pecos, the Kid and Garrett might take part in an impromptu shooting match. Billy was ambidextrous, and people said he could shoot a pistol with one hand just as well as the other, although he favored the right hand whenever he got into a “jackpot.” According to Paulita Maxwell, Billy was better than Garrett with the revolver. She remembered a time when a terror-stricken jackrabbit on a Fort

Sumner lane somehow managed to dodge every bullet Garrett fired at him. The Kid whipped out his revolver and pancaked the rabbit with his first shot. Maybe this happened, maybe not.

Others considered Garrett the better shot, possibly even the best man with a revolver in the entire Southwest. And Garrett did not rate Billy’s shooting nearly as high as many who were acquainted with the Kid. When asked if Billy was a good shot, Garrett admitted that he was, but he added that the Kid was “no better than the majority of men who are constantly handling and using six-shooters. He shot well, though, and he shot well under all circumstances, whether in danger or not.” That last was the key, of course. As Garrett remarked years later, “A man with nerve behind a gun is worth twenty-five who are after him.” There is no question that Billy Bonney had nerve; Joe Grant discovered that in January 1880.

Grant had shown up at Fort Sumner, presumably from Texas, with no job and apparently no interest in finding one—never a good sign. But somehow he had enough means to keep himself in liquor for several days. He had immediately buddied up with the Kid and his associates, who were also hanging around and not working. At some point, Grant got it into his head that he would be quite the hombre if he took out the Kid. Some claim he came to Fort Sumner with that purpose, but Grant’s scheme, which he let slip one day, could also have been the whiskey talking. In any event, Grant’s blustering got back to Billy, who remained friendly with the Texan but kept his eyes on the man.

On January 10, a Saturday, Billy and two friends rode up on a small herd of cattle that James Chisum (brother of John) and three of his cowhands were moving southward. The cattle had been stolen from the Chisum range—almost certainly by the Kid—and Chisum was taking them back. With a straight face, Billy asked to inspect the herd, as if he might actually find an animal that had not been given Chisum’s Jinglebob brand. After Billy had his look, he invited Chisum

and his men to have a drink at Bob Hargrove’s saloon in Fort Sumner, less than a mile away.

Joe Grant was in the saloon when Billy, Chisum, and the others got there, and Grant was well inebriated already. As Jack Finan, one of Chisum’s men, walked past the drunken Texan, Grant yanked Finan’s pearl-handled revolver from its holster and replaced it with his own. Billy immediately stepped over to Grant and said, “That’s a beauty, Joe,” and then reached out and took the pistol from Grant. Billy examined the six-shooter’s cylinder and noticed that three of the six chambers were empty. He carefully rotated the cylinder so that when the gun was cocked and the trigger pulled, the gun’s hammer would fall on an empty chamber. The Kid then casually handed the pistol back to Grant.

“Pard, I’ll kill a man quicker’n you will for the whisky,” Grant said to Billy.

“What do you want to kill anybody for?” Billy said. “Put up your pistol and let’s drink.”

Pistol still in hand, Grant stepped behind the bar and used the gun’s barrel to smash the glasses and decanters on the counter. Everyone watched nervously as Grant pointed the pistol wildly around the saloon. Billy pulled his six-shooter. “Let me help you break up housekeeping, pard,” he said, and gleefully joined Grant in finishing off the saloon’s glassware.

Then Grant saw James Chisum across the room and mistook him for John Chisum. And, for some unknown reason, Grant had a strong grudge against the Pecos cattle baron.

“I want to kill John Chisum, anyhow, the damned old son of a bitch,” Grant said.

“You’ve got the wrong pig by the ear, Joe,” Billy said, “that’s not John Chisum.”

“That’s a lie,” Grant screamed. “I know better!”

Quick as a flash, Grant pointed his pistol at Billy and pulled the

trigger. There was a click, then the sound of Grant cursing as he again cocked the gun’s hammer. But that was immediately followed by the loud blast of Billy’s six-shooter as he sent a lead ball into Joe Grant’s head. Grant collapsed behind the blood-splattered bar. A moment later, someone asked the Kid if he was sure Grant was dead. Billy nodded his head confidently.

“No fear,” he said. “The corpse is there, sure, ready for the undertaker.”

The following day, Billy, Tom Folliard, Charlie Bowdre, and a Charlie Thomas went to pick up their mail at the post office in Sunnyside, approximately five miles above Fort Sumner. Bowdre casually told the postmaster, Milnor Rudolph, that another man had “turned up his toes” at Sumner. That got Rudolph’s attention, and he asked the name of the deceased. Bowdre said it was Joe Grant, and he had been shot by the Kid. Rudolph then looked at Billy and asked him why he killed Grant.

“His gun wouldn’t fire,” Billy coolly explained, “and mine would.”

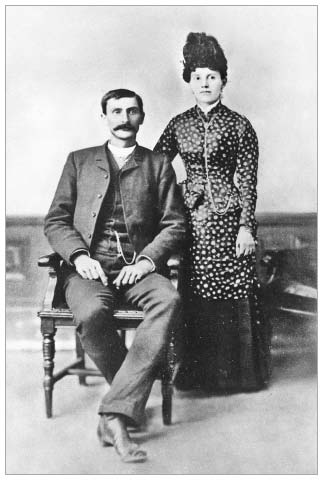

Four days after Billy sent the local undertaker a gift of Joe Grant, Pat Garrett stood before the parish priest at Anton Chico, a village ninety miles northwest of Fort Sumner, and married Polinaria Gutiérrez, the daughter of José Dolores and Feliciana Gutiérrez. Garrett’s period of mourning had been brief, but this was not unusual in a land where time was the last thing one could count on. Polinaria’s first name was actually Apolinaria, although her friends and family called her “La Negra” or simply “Negra,” presumably because of her dark complexion. Garrett towered over the petite girl, who may have been as young as sixteen. And although Garrett was basically a nonbeliever, Polinaria was a devout Catholic, and that meant the rites had to be performed by a priest. This may have seemed even more important because Garrett’s first marriage had been performed without a priest, and that had not worked out so well.

Pat and Apolinaria Garrett, circa 1880.

University of Texas at El Paso Library, Special Collections Department

NEARLY THIRTY YEARS OLD

and married, Pat Garrett was tired of struggling to make a living at Fort Sumner—and tired of the criminals who seemed to have the place under their control. He wanted something better. So, too, did Pecos Valley cattleman and entrepreneur Captain Joseph C. Lea. Lea was a former Missouri guerrilla who had fought alongside the likes of Cole Younger and Frank James under Quantrill and Jo Shelby during the Civil War. Pardoned by President Andrew Johnson in 1865, Lea had tried his hand at farming and livestock trading before coming to New Mexico Territory in 1875. Early in 1878, Lea had moved his family to Roswell, where he soon purchased the town’s two adobe buildings, a store and a hotel. Later that same year, he was elected a Lincoln County commissioner, a good indication of the favorable first impression he had made on the region’s ranchers and settlers. What Lea wanted was to see an end to the thieving and violence in the Pecos Valley so that farming and livestock raising, not to mention little Roswell itself, could prosper. That meant getting rid of Billy the Kid and his cohorts. That meant, ultimately, the end of an era.

For this to happen, he knew that Lincoln County needed a new sheriff, one who understood the risks but was willing to see the job to its conclusion. Lea, who was every bit as tall as Garrett, became convinced that Garrett was the man for this job. He persuaded Garrett to pick up and move to the Roswell area (Fort Sumner was just outside of Lincoln County) and run for election as sheriff that fall. By early June, Garrett and Polinaria were settled into their new home, and the census taker recorded Garrett’s occupation as farmer.

William Bonney was noted in that census. He shared an adobe dwelling at Fort Sumner with his friends Charlie and Manuela Bowdre (it was rumored that he and Charlie shared more than the house). The census taker wrote down that Charlie and Billy both “work in cattle,”

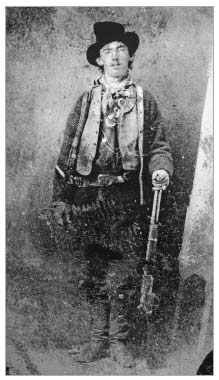

which, like most things about Billy, was true yet not true. Sometime that same year, a traveling photographer arrived at Fort Sumner. With tintype portraits going for only a few cents apiece, a professional photographer could draw settlers from miles around. Billy decided to have his picture taken, if only to have a few tintypes to present to the girls he was sweet on. Although Paulita Maxwell insisted that Billy

was a neat and tasteful dresser around Fort Sumner, Billy is rather odd-looking in this tintype, wearing rumpled, trail-worn clothes: a loose sweater, unbuttoned vest, a showy bib-front shirt embroidered with a large anchor across the chest, a bandanna knotted clumsily about the neck, and a narrow-brimmed felt hat with a large dent in the crown.

Billy the Kid, from the tintype made at Fort Sumner.

Collection of the author

Billy was never without a weapon, and in the photograph he is grasping the muzzle of a Model 1873 Winchester carbine, with its butt resting on the floor. Around his waist is a cartridge belt and holster with the curved butt of a six-shooter sticking out. These were the tools of the Kid’s trade—and what he needed to survive. Billy apparently paid for four tintypes, which would have been made simultaneously with a camera that featured four individual lenses mounted on the front. After developing the tin plate with its four identical images, the photographer would simply snip it into four parts and mount the portraits in thin paper mattes. The single surviving photograph of Billy the Kid in all his glory is anything but a flattering portrait—his mouth is partially open, exposing his buckteeth, and his eyelids appear to be drooping, snake-eyed. Nearly everyone remembered Billy as attractive, extremely likable, and full of life. It is as if he was just too big—or too elusive—to be captured in a tintype that would fit in the palm of one’s hand.

At the time that this photograph was taken, Billy had become the most prominent member of a very successful gang of livestock thieves that operated back and forth between the rowdy cow town of Tascosa, Texas, southwest to the mining boomtown of White Oaks, New Mexico, a distance of some three hundred miles. With markets on both sides of the state line, and several large ranches with not nearly enough cowhands to be everywhere at once, it was easy enough to round up a few head of cattle, alter the brands, write up a fake bill of sale, and be gone down the trail before the owner knew what hit him. And with beef bringing between $15 and $25 per head (the gang got

$10 for their stolen beef ), a loss of fifty head of cattle was a painful hit to the account books. The cattlemen of this area knew who Billy was and were desperate that he and his cohorts be captured or run out of the country.